CORDIC

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

CORDIC (digit-by-digit method, Volder's algorithm) (for COordinate Rotation DIgital Computer) is a simple and efficient algorithm to calculate hyperbolic and trigonometric functions. It is commonly used when no hardware multiplier is available (e.g., simple microcontrollers and FPGAs) as the only operations it requires are addition, subtraction, bitshift and table lookup.

The modern CORDIC algorithm was first described in 1959 by Jack E. Volder. It was developed at the aeroelectronics department of Convair to replace the analog resolver in the B-58 bomber's navigation computer,[1] although it is similar to techniques published by Henry Briggs as early as 1624. John Stephen Walther at Hewlett-Packard further generalized the algorithm, allowing it to calculate hyperbolic and exponential functions, logarithms, multiplications, divisions, and square roots.[2]

Originally, CORDIC was implemented using the binary numeral system. In the 1970s, decimal CORDIC became widely used in pocket calculators, most of which operate in binary-coded-decimal (BCD) rather than binary. CORDIC is particularly well-suited for handheld calculators, an application for which cost (eg, chip gate count has to be minimised) is much more important than is speed. Also the CORDIC subroutines for trigonometric and hyperbolic functions can share most of their code.

Contents |

[edit] Application

CORDIC is generally faster than other approaches when a hardware multiplier is unavailable (e.g., in a microcontroller based system), or when the number of gates required to implement the functions it supports should be minimized (e.g., in an FPGA). On the other hand, when a hardware multiplier is available (e.g., in a DSP microprocessor), table-lookup methods and power series are generally faster than CORDIC.

[edit] Mode of operation

CORDIC can be used to calculate a number of different functions. This explanation shows how to use CORDIC in rotation mode to calculate sine and cosine of an angle, and assumes the desired angle is given in radians and represented in a fixed point format. To determine the sine or cosine for an angle β, the y or x coordinate of a point on the unit circle corresponding to the desired angle must be found. Using CORDIC, we would start with the vector v0:

In the first iteration, this vector would be rotated 45° counterclockwise to get the vector v1. Successive iterations will rotate the vector in one or the other direction by half the amount of the previous iteration until the desired angle has been achieved.

More formally, every iteration calculates a rotation, which is performed by multiplying the vector vi with the rotation matrix Ri:

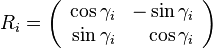

The rotation matrix R is given by:

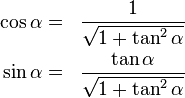

Using the following two trigonometric identities

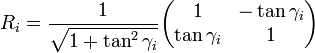

the rotation matrix becomes:

The expression for the rotated vector vi + 1 = Rivi then becomes:

where xi and yi are the components of vi. Restricting the angles γi so that tanγi takes on the values  the multiplication with the tangent can be replaced by a division by a power of two, which is efficiently done in digital computer hardware using a bit shift. The expression then becomes:

the multiplication with the tangent can be replaced by a division by a power of two, which is efficiently done in digital computer hardware using a bit shift. The expression then becomes:

where

and σi can have the values of −1 or 1 and is used to determine the direction of the rotation: if the angle βi is positive then σi is 1, otherwise it is −1.

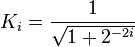

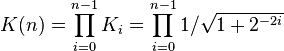

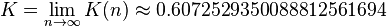

We can ignore Ki in the iterative process and then apply it afterward by a scaling factor:

which is calculated in advance and stored in a table. Additionally it can be noted that

to allow further reduction of the algorithm's complexity. After a sufficient number of iterations, the vector's angle will be close to the wanted angle β. For most ordinary purposes, 40 iterations (n = 40) is sufficient to obtain the correct result to the 10th decimal place.

The only task left is to determine if the rotation should be clockwise or counterclockwise at every iteration (choosing the value of σ). This is done by keeping track of how much we rotated at every iteration and subtracting that from the wanted angle, and then checking if βn + 1 is positive and we need to rotate clockwise or if it is negative we must rotate counterclockwise in order to get closer to the wanted angle β.

The values of γn must also be precomputed and stored. But for small angles, arctan(γn) = γn in fixed point representation, reducing table size.

As can be seen in the illustration above, the sine of the angle β is the y coordinate of the final vector vn, while the x coordinate is the cosine value.

[edit] Implementation in MATLAB/GNU Octave

The following is a MATLAB/GNU Octave implementation of CORDIC that does not rely on any transcendental functions except in the precomputation of tables. If the number of iterations n is predetermined, then the second table can be replaced by a single constant. The two-by-two matrix multiplication represents a pair of simple shifts and adds. With MATLAB's standard double-precision arithmetic and "format long" printout, the results increase in accuracy for n up to about 48.

function v = cordic(beta,n)

% This function computes v = [cos(beta), sin(beta)] (beta in radians)

% using n iterations. Increasing n will increase the precision.

if beta < -pi/2 || beta > pi/2

if beta < 0

v = cordic(beta + pi, n);

else

v = cordic(beta - pi, n);

end

v = -v; % flip the sign for second or third quadrant

return

end

% Initialization of tables of constants used by CORDIC

% need a table of arctangents of negative powers of two, in radians:

% angles = atan(2.^-(0:27));

angles = [ ...

0.78539816339745 0.46364760900081 0.24497866312686 0.12435499454676 ...

0.06241880999596 0.03123983343027 0.01562372862048 0.00781234106010 ...

0.00390623013197 0.00195312251648 0.00097656218956 0.00048828121119 ...

0.00024414062015 0.00012207031189 0.00006103515617 0.00003051757812 ...

0.00001525878906 0.00000762939453 0.00000381469727 0.00000190734863 ...

0.00000095367432 0.00000047683716 0.00000023841858 0.00000011920929 ...

0.00000005960464 0.00000002980232 0.00000001490116 0.00000000745058 ];

% and a table of products of reciprocal lengths of vectors [1, 2^-j]:

Kvalues = [ ...

0.70710678118655 0.63245553203368 0.61357199107790 0.60883391251775 ...

0.60764825625617 0.60735177014130 0.60727764409353 0.60725911229889 ...

0.60725447933256 0.60725332108988 0.60725303152913 0.60725295913894 ...

0.60725294104140 0.60725293651701 0.60725293538591 0.60725293510314 ...

0.60725293503245 0.60725293501477 0.60725293501035 0.60725293500925 ...

0.60725293500897 0.60725293500890 0.60725293500889 0.60725293500888 ];

Kn = Kvalues(min(n, length(Kvalues)));

% Initialize loop variables:

v = [1;0]; % start with 2-vector cosine and sine of zero

poweroftwo = 1;

angle = angles(1);

% Iterations

for j = 0:n-1;

if beta < 0

sigma = -1;

else

sigma = 1;

end

factor = sigma * poweroftwo;

R = [1, -factor; factor, 1];

v = R * v; % 2-by-2 matrix multiply

beta = beta - sigma * angle; % update the remaining angle

poweroftwo = poweroftwo / 2;

% update the angle from table, or eventually by just dividing by two

if j+2 > length(angles)

angle = angle / 2;

else

angle = angles(j+2);

end

end

% Adjust length of output vector to be [cos(beta), sin(beta)]:

v = v * Kn;

return

[edit] Hardware implementation

The primary use of the CORDIC algorithms in a hardware implementation is to avoid time-consuming complex multipliers. The computation of phase for a complex number can be easily implemented in a hardware description language using only adder and shifter circuits bypassing the bulky complex number multipliers. Fabrication techniques have steadily improved, and complex numbers can now be handled directly without too high a cost in time, power consumption, or excessive die space, so the use of CORDIC techniques is not as critical in many applications as they once were.

[edit] Related algorithms

CORDIC is part of the class of "shift-and-add" algorithms, as are the logarithm and exponential algorithms derived from Henry Briggs' work. Another shift-and-add algorithm which can be used for computing many elementary functions is the BKM algorithm, which is a generalization of the logarithm and exponential algorithms to the complex plane. For instance, BKM can be used to compute the sine and cosine of a real angle x (in radians) by computing the exponential of 0 + ix, which is cosx + isinx. The BKM algorithm is slightly more complex than CORDIC, but has the advantage that it does not need a scaling factor (K).

[edit] History

Volder was inspired by the following formula in the 1946 edition of the CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics:

with  [1]

[1]

Some of the prominent early applications of CORDIC were in the Convair navigation computers CORDIC I to CORDIC III[1], the Hewlett-Packard HP-9100 and HP-35 calculators[4], the Intel 80x87 coprocessor series until Intel 80486, and Motorola 68881[5].

Decimal CORDIC was first suggested by Hermann Schmid and Anthony Bogacki.[6]

[edit] Notes

- ^ a b c J. E. Volder, "The Birth of CORDIC", J. VLSI Signal Processing 25, 101 (2000).

- ^ J. S. Walther, "The Story of Unified CORDIC", J. VLSI Signal Processing 25, 107 (2000).

- ^ J.-M. Muller, Elementary Functions: Algorithms and Implementation, 2nd Edition (Birkhäuser, Boston, 2006), p. 134.

- ^ D. Cochran, "Algorithms and Accuracy in the HP 35", Hewlett Packard J. 23, 10 (1972).

- ^ R. Nave, "Implementation of Transcendental Functions on a Numerics Processor", Microprocessing and Microprogramming 11, 221 (1983).

- ^ H. Schmid and A. Bogacki, "Use Decimal CORDIC for Generation of Many Transcendental Functions", EDN Magazine, February 20, 1973, p. 64.

[edit] References

- Jack E. Volder, The CORDIC Trigonometric Computing Technique, IRE Transactions on Electronic Computers, September 1959

- Daggett, D. H., Decimal-Binary conversions in CORDIC, IRE Transactions on Electronic Computers, Vol. EC-8 #5, pp335-339, IRE, September 1959.

- J. E. Meggitt, Pseudo Division and Pseudo Multiplication Processes, IBM Journal, April 1962.

- Vladimir Baykov, Problems of Elementary Functions Evaluation Based on Digit by Digit (CORDIC) Technique, PhD thesis, Leningrad State Univ. of Electrical Eng., 1972

- Schmid, Hermann, Decimal computation. New York, Wiley, 1974

- V.D.Baykov,V.B.Smolov, Hardware implementation of elementary functions in computers, Leningrad State University, 1975, 96p.*Full Text

- Senzig, Don, Calculator Algorithms, IEEE Compcon Reader Digest, IEEE Catalog No. 75 CH 0920-9C, pp139-141, IEEE, 1975.

- V.D.Baykov,S.A.Seljutin, Elementary functions evaluation in microcalculators, Moscow, Radio & svjaz,1982,64p.

- Vladimir D.Baykov, Vladimir B.Smolov, Special-purpose processors: iterative algorithms and structures, Moscow, Radio & svjaz, 1985, 288 pages

- M. E. Frerking, Digital Signal Processing in Communication Systems, 1994

- Vitit Kantabutra, On hardware for computing exponential and trigonometric functions, IEEE Trans. Computers 45 (3), 328-339 (1996)

- Andraka, Ray, A survey of CORDIC algorithms for FPGA based computers

- Henry Briggs, Arithmetica Logarithmica. London, 1624, folio

- CORDIC Bibliography Site

- The secret of the algorithms, Jacques Laporte, Paris 1981

- Digit by digit methods, Jacques Laporte, Paris 2006

[edit] External links

- The CORDIC Algorithm

- CORDIC FAQ

- CORDIC Vectoring with Arbitrary Target Value

- USENET discussion

- BASIC Stamp, CORDIC math implementation

- PicBasic Pro, Pic18 CORDIC math implementation

- Another USENET discussion

- CORDIC information

- CORDIC implementation in verilog.

- CORDIC as implemented in the ROM of the HP-35 - Jacques Laporte (step by step analysis, simulator running the real ROM with breakpoints and trace facility.

- Tutorial and MATLAB Implementation - Using CORDIC to Estimate Phase of a Complex Number

- Simple C code for fixed-point CORDIC