Iranian Revolution

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Iranian Revolution |

|

|

Articles

|

|

|

|

|

The Iranian Revolution (mostly known as the Islamic Revolution,[1][2][3][4][5][6] Persian: انقلاب اسلامی, Enghelābe Eslāmi) refers to events involving the overthrow of Iran's monarchy under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and its replacement with an Islamic republic under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of the revolution.[7] It has been called an event that "made Islamic fundamentalism a political force ... from Morocco to Malaysia."[8]

The first major demonstrations against the Shah began in January 1978.[9] Between August and December 1978 strikes and demonstrations paralyzed the country. The shah left Iran for exile in mid-January 1979, and two meeks later Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Tehran to a greeting by several million Iranians.[10] The royal regime collapsed shortly after on February 11 when guerrillas and rebel troops overwhelmed troops loyal to the Shah in armed street fighting. Iran voted by national referendum to become an Islamic Republic on April 1, 1979,[11] and to approve a new theocratic constitution whereby Khomeini became Supreme Leader of the country, in December 1979.

The revolution was unique for the surprise it created throughout the world:[12] it lacked many of the customary causes of revolution — defeat at war, a financial crisis, peasant rebellion, or disgruntled military;[13] produced profound change at great speed;[14] was massively popular;[15] overthrew a regime heavily protected by a lavishly financed army and security services;[16][17] and replaced an ancient monarchy with a theocracy based on Guardianship of the Islamic Jurists (or velayat-e faqih). Its outcome — an Islamic Republic "under the guidance of an 80-year-old exiled religious scholar from Qom" — was, as one scholar put it, "clearly an occurrence that had to be explained."[18]

Not so unique but more intense is the dispute over the revolution's results. For some it was an era of heroism and sacrifice that brought forth nothing less than the nucleus of a world Islamic state — "a perfect model of splendid, humane, and divine life… for all the peoples of the world."[19] At the other extreme, disillusioned Iranians explain the revolution as a time when "for a few years we all lost our minds",[20] and which "promised us heaven, but... created a hell on earth."[21]

[edit] Background and causes of the revolution

[edit] Causes of the revolution

The ideology of the revolution can be summarized as populist, nationalist and most of all Shi'a. The revolution was, at least in part, a conservative backlash to the Westernizing and secularizing efforts of the Western-backed Shah.[22]

Explanations advanced for why the revolution occurred and took the form it did include the unpopularity of the Shah's regime. The perception that the Shah was beholden to — if not a puppet of — a non-Muslim Western power, (the United States),[23][24] whose culture was contaminating that of Iran's; and that the Shah's regime was oppressive, brutal,[25][26] corrupt, and extravagant.[27][25] Basic functional failures of the regime have also been blamed for the fall of the shah — economic bottlenecks, shortages and inflation; the regime's overly-ambitious economic program;[28] the failure of its security forces to deal with protest and demonstration;[29] the overly centralized royal power structure.[30] Also blamed was the extraordinarly large size of the anti-shah movment which meant that there "were literally too many protesters to arrest", and that the security forces were overwhelmed.[31]

The success of Islamism and Khomeini in the revolution is credited in part on the spread of the Shia version of the Islamic revival that opposed Westernization, saw Ayatollah Khomeini as following in the footsteps of the beloved Shi'a Imam Husayn ibn Ali, and the Shah in those of Husayn's foe, the hated tyrant Yazid I;[32] Also credited was the underestimation of Khomeini's Islamist movement by both the Shah's regime — who considered them a minor threat compared to the socialists[33][34][35] — and by the anti-Shah secularists — who thought the Khomeinists could be sidelined.[36]

[edit] Historical background of the revolution (1906-1977)

The dynasty that the revolution overthrew — the Pahlavi dynasty — was known for its autocracy, its focus on modernization and Westernization and for its disregard for religious[37] and democratic measures in Iran's constitution.

The founder of the dynasty, army general Reza Pahlavi, replaced Islamic laws with western ones, and forbade traditional Islamic clothing, separation of the sexes and veiling of women (hijab).[38] Women who resisted his ban on public hijab had their chadors forcibly removed and torn. In 1935 a rebellion by pious Shi'a at the shrine of Imam Reza in Mashad was crushed on his orders with dozens killed and hundreds injured,[39] rupturing relations between the Shah and pious Shia in Iran. [40][41]

[edit] The Shah comes to power

Reza Shah was deposed in 1941 by an invasion of allied British and Soviet troops who believed him to be sympathetic with the allies' enemy Nazi Germany. His son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was installed by the allies as monarch. Prince Pahlavi (later crowned shah) reigned until the 1979 revolution with one brief interruption. In 1953 he fled the country after a power-struggle with his Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh. Mossadegh is remembered in Iran for having been voted into power through a democratic election, nationalizing Iran's British-owned oil fields, and being deposed in a military coup d'état organized by an American CIA operative and aided by the British MI6. Thus foreign powers were involved in both the installation and restoration of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

The shah maintained a close relationship with the United States, both regimes sharing a fear of/opposition to the expansion of Soviet/Russian state, Iran's powerful northern neighbor. Leftist, nationalist and religious groups attacked his government (often from outside Iran as they were suppressed within) for violating the Iranian constitution, political corruption, and the political oppression by the SAVAK (secret police).

[edit] Rise of Ayatollah Khomeini

Of ultimate political importance to the revolution were figures in the Shi'a clergy or Ulema, who had shown themselves to be a vocal political force in Iran with the 19th century Tobacco Protests against a concession to a foreign interest. The clergy had a significant influence on the majority of Iranians, who tended to be religious, traditional, and alienated from any process of Westernization. Shia cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of the Iranian revolution, first came to political prominence in 1963 when he lead opposition to the Shah and his program of reforms known as the "White Revolution", which aimed to break up landholdings owned by some Shi’a clergy, allow women to vote and religious minorities to hold office, and grant women legal equality in marital issues.

Khomeini declared that the Shah had "embarked on the destruction of Islam in Iran"[42] and publicly denounced the Shah as a "wretched miserable man." Following Khomeini's arrest on June 5, 1963, three days of major riots erupted throughout Iran, with Khomeini supporters claiming 15,000 were killed by police fire[43] Khomeini was detained and kept under house arrest for 8 months. After his release he continued his agitation against the Shah, condemning the regimes's close cooperation with Israel and its "capitulations" — the extension of diplomatic immunity to American government personnel in Iran. In November 1964 Khomeini was re-arrested and sent into exile where he remained for 14 years until the revolution.

A period of "disaffected calm" followed.[44] Despite political repression the budding Islamic revival began to undermine the idea of Westernization as progress that was the basis of the Shah's secular regime and form the ideology of the revolution. Jalal Al-e-Ahmad's idea of Gharbzadegi - that Western culture was a plague or an intoxication to be eliminated[45]; Ali Shariati's vision of Islam as the one true liberator of the Third World from oppressive colonialism, neo-colonialism, and capitalism[46]; and Morteza Motahhari's popularized retellings of the Shia faith, all spread and gained listeners, readers and supporters.[45] Most importantly, Khomeini preached that revolt, and especially martyrdom, against injustice and tyranny was part of Shia Islam,[47] and that Muslims should reject the influence of both capitalism and communism with the slogan "Neither East, nor West - Islamic Republic!" (Persian: نه شرقی نه غربی جمهوری اسلامی)

To replace the shah's regime Khomeini developed the ideology of velayat-e faqih (guardianship of the jurist) as government, that Muslims — in fact everyone — required "guardianship," in the form of rule or supervision by the leading Islamic jurist or jurists.[48] Such rule would protect Islam from deviation from traditional sharia law, and in so doing eliminate poverty, injustice, and the "plundering" of Muslim land by foreign unbelievers.[49] Establishing and obeying this Islamic government was "actually an expression of obedience to God", ultimately "more necessary even than prayer and fasting" in Islam,[50] and a commandment for all the world, not one confined to Iran.[51]

Publicly, Khomeini focused on the socio-economic problems of the shah's regime (corruption, unequal income and development),[52] not his solution of rule by Islamic jurists. He believed a propaganda campaign by Western imperialists had prejudiced most Iranians against theocratic rule. [53][54] But his book was widely distributed in religious circles, especially among Khomeini's students (talabeh), ex-students (clerics), and traditional business leaders (bazaari). A powerful and efficient network of opposition began to develope inside Iran,[55] employing mosque sermons, smuggled cassette speeches by Khomeini, and other means. Added to this religious opposition were secular and Islamic modernist students and guerrilla groups[56] who admired Khomeini's history of resistance, though they were to clash with his theocracy and be suppressed by his movement after the revolution.

[edit] 1970-1977: Pre-revolutionary conditions

Several events in the 1970s set the stage for the 1979 revolution:

In October 1971, the 2,500th anniversary of the founding of the Persian Empire was held at the site of Persepolis. Only foreign dignitaries were invited to the three-day party whose extravagances included over one ton of caviar, and preparation by some two hundred chefs flown in from Paris. Cost was officially $40 million but estimated to be more in the range of $100–120 million.[57] Meanwhile drought ravaged the provinces of Baluchistan, Sistan, and even Fars where the celebrations were held. "As the foreigners reveled on drink forbidden by Islam, Iranians were not only excluded from the festivities, some were starving."[58]

By late 1974 the oil boom had begun to produce not "the Great Civilization" promised by the Shah, but an "alarming" increase in inflation and waste and an "accelerating gap" between the rich and poor, the city and the country.[59] Nationalistic Iranians were angered by the tens of thousand of skilled foreign workers who came to Iran, many of them to help operate the already unpopular and expensive American high-tech military equipment that the Shah had spent hundreds of millions of dollars on.

The next year the Rastakhiz party was created. It became not only the only party Iranians were permitted to belong to, but one the "whole adult population" was required to belong and pay dues to.[60] The party attempted by to take a populist stand fining and jailing merchants in its "anti-profiteering" campaigns, but this proved not only economically harmful but also politically counterproductive. Inflation morphed into a black market and business activity declined. Merchants were angered and politicized.[61]

In 1976, the Shah's government angered pious Iranian Muslims by changing the first year of the Iranian solar calendar from the Islamic hijri to the ascension to the throne by Cyrus the Great. "Iran jumped overnight from the Muslim year 1355 to the royalist year 2535."[62] The same year the Shah declared economic austerity measures to dampen inflation and waste. The resulting unemployment disproportionately affected the thousands of recent poor and unskilled migrants to the cities. As cultural and religious conservatives, many of these people, already disposed to view the Shah's secularism and Westernization as "alien and wicked",[63] went on to form the core of revolution's demonstrators and "martyrs".[64]

In 1977 a new American President, Jimmy Carter, was inaugurated. Carter sought to make American post-Vietnam foreign policy and power excersise more benevolent, and created a special Office of Human Rights. It sent the Shah a "polite reminder" of the importance of political rights and freedom. The Shah responded by granting amnesty to 357 political prisoners in February, and allowing Red Cross to visit prisons, beginning what is said to be 'a trend of liberalization by the Shah'. Through the late spring, summer and autumn liberal opposition formed organizations and issued open letters denouncing the regime.[65] Later that year a dissent group (the Writers' Association) gathered without the customary police break-up and arrests, starting a new era of political action by the Shah's opponents.[66]

That year also saw the death of the very popular and influential modernist Islamist leader Ali Shariati, allegedly at the hands of SAVAK, removing a potential revolutionary rival to Khomeini. Finally, in October Khomeini's son Mostafa died. Though the cause appeared to be a heart attack, anti-Shah groups blamed SAVAK poisoning and proclaimed him a 'martyr.' A subsequent memorial service for Mostafa in Tehran put Khomeini back in the spotlight and began the process of building Khomeini into the leading opponent of the Shah.[67][68]

[edit] Opposition groups and organizations

Constitutionalist, Marxist, and Islamist groups opposed the Shah:

The very first signs of opposition in 1977 came from Iranian constitutionalist liberals. Based in the urban middle class, this was a section of the population that was fairly secular and wanted the Shah to adhere to the Iranian Constitution of 1906 rather than religious rule.[69] Prominent in it was Mehdi Bazargan and his liberal, moderate Islamic group Freedom Movement of Iran, and the more secular National Front.

The clergy were divided, allying variously with the liberals, Marxists and Islamists. The various anti-Shah groups operated from outside Iran, mostly in London, Paris, Iraq, and Turkey. Speeches by the leaders of these groups were placed on audio cassettes to be smuggled into Iran. Khomeini, who was in exile in Iraq, worked to unite clerical and secular, liberal and radical opposition under his leadership[70] by avoiding specifics — at least in public — that might divide the factions.[71]

Marxists groups were illegal and heavily suppressed by SAVAK internal security apparatus. They included the communist Tudeh Party of Iran; two armed organizations, the Organization of Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas (OIPFG) and the breakaway Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas (IPFG); and some minor groups.[72] The guerillas aim was to defeat the Pahlavi regime by assassination and guerilla war. Although they played an important part in the 1979 overthrow of the regime, they had been weakened considerably by government repression and factionalization in the first half of the 1970s.[73]

Islamists were divided into several groups. The Freedom Movement of Iran, made up of religious members of the National Front of Iran who wanted to use lawful political methods against the Shah and led by Bazargan and Mahmoud Taleghani. The People's Mujahedin of Iran, a quasi-Marxist armed organization that opposed the influence of the clergy and later fought Khomeini's Islamic government.

The Islamist group that ultimately prevailed was that containing the core supporters of Ayatollah Khomeini. Amongst them were some minor armed Islamist groups which joined together after the revolution in the Mojahedin of the Islamic Revolution Organization. The Coalition of Islamic Societies was founded by religious bazaaris[74] (traditional merchants). The Combatant Clergy Association comprised Motahhari, Beheshti, Bahonar, Rafsanjani and Mofatteh who later became the major leaders of the Islamic Republic. They used a cultural approach to fight the Shah.

Because of internal repression, opposition groups abroad, like the Confederation of Iranian students, the foreign branch of Freedom Movement of Iran and the Islamic association of students, were important to the revolution.

[edit] Outbreak of Revolution

[edit] The first demonstrations of late 1977

The first militant anti-Shah demonstrations were in October 1977, after the death of Khomeini's son Mostafa. .[75] Khomeini's activists numbered "perhaps a few hundred in total", but over the coming months they grew to a mass of several thousand demonstrators in most cities of Iran.[76]

The first causualties suffered in major demonstrations against the Shah came in January 1978. Hundreds of Islamist students and religious leaders in the city of Qom were furious over a story in the government-controlled press they felt was libelous. The army was sent in, dispersing the demonstrations and killing several students (two to nine according to the government, 70 or more according to the opposition).[77][78]

According to the Shi'ite customs, memorial services (called Arba'een) are held forty days after a person's death. In mosques across the nation, calls were made to honour the dead students. Thus on February 18 groups in a number of cities marched to honour the fallen and protest against the rule of the Shah. This time, violence erupted in Tabriz, were five hundred demonstrators were killed according to the opposition, ten according to the government. The cycle repeated itself, and on March 29, a new round of protests began across the nation. Luxury hotels, cinemas, banks, government offices, and other symbols of the Shah regime were destroyed; again security forces intervened, killing many. On May 10 the same occurred.

[edit] Ayatollah Shariatmadari joins the opposition

In May, government commandos burst into the home of Ayatollah Kazem Shariatmadari, a leading cleric and political moderate, and shot dead one of his followers right in front of him. Shariatmadari abandoned his quietist stance and joined the opposition to the Shah.[79]

The Shah attempted to appease protestors by dampening inflation, making appeals to the moderate clergy, and by firing his head of SAVAK and promising free elections the next June.[80] But the anti-inflationary cutbacks in spending led to layoffs — particularly among young, unskilled workers living in city slums. By summer 1978, these workers, often from traditional rural backgrounds, joined the street protests in massive numbers. Other workers went on strike and by November the economy was crippled by shutdowns.[81]

[edit] The Shah and the United States

Facing a revolution, the Shah appealed to the United States for support. Because of Iran's history and strategic location, it was important to the United States. Iran shared a long border with America's cold war rival, the Soviet Union, and the largest, most powerful country in the oil-rich Persian Gulf. The Shah had long been pro-American, but the Pahlavi regime had also recently garnered unfavorable publicity in the West for its human rights record.[82] In the United States Iran was not considered in danger of revolution. A CIA analysis in August 1978, just six months before the Shah fled Iran, had concluded that the country "is not in a revolutionary or even a pre-revolutionary situation." [83]

According to historian Nikki Keddie, the administration of then President Carter followed "no clear policy" on Iran.[84] The U.S. ambassador to Iran, William H. Sullivan, recalls that the U.S. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski “repeatedly assured Pahlavi that the U.S. backed him fully." On November 4, 1978, Brzezinski called the Shah to tell him that the United States would "back him to the hilt." But at the same time, certain high-level officials in the State Department believed the revolution was unstoppable.[85] After visiting the Shah in summer of 1978, Secretary of the Treasury Blumenthal complained of the Shah's emotional collapse, reporting, "You've got a zombie out there."[86] Brzezinski and Energy Secretary James Schlesinger were adamant in their assurances that the Shah would receive military support.

Another historian (Charles Kurzman), argues that rather than being indecisive, or sympathetic to the revolution, the Carter administration was consistently supportive of the Shah and urged the Iranian military to stage a "last-resort coup d'etat" even after the regime's cause was hopeless. [87]

Many Iranians believe the lack of intervention and sympathetic remarks about the revolution by high-level American officials indicate the U.S. "was responsible for Khomeini's victory."[84] [88] A more extreme position asserts that the Shah's overthrow was the result of a "sinister plot to topple a nationalist, progressive, and independent-minded monarch."[89]

[edit] Abadan cinema fire

By Summer 1978 the level of protest had been at a steady state for four months — about ten thousand participants in each major city (with the exception of Isfahan where protests were larger and Tehran where they were smaller). This amounted to an "almost fully mobilized `mosque network,`" of pious Iranian Muslims, but a small minority of the "more than 15 million" adults in Iran. Worse for the momentum of the movement, on June 17 1978 the 40-day mourning cycle of mobilization of protest — where mourning for protesters killed in earlier demonstrations led to street protests 40 days after their death which resulted in the deaths of more protesters who could be mourned 40-days later in new demonstrations — ended with a call for calm and a stay-at-home strike by moderate religious leader Shariatmadari.[90]

This impass was broken in August 1978 when over 400 people died in the Cinema Rex Fire arson attack in Abadan. Movie theaters had been a common target of Islamist demonstrators[91][92] but such was the distrust of the regime and effectiveness of its enemies' communication skills that the public believed SAVAK had set the fire in an attempt to frame the opposition.[93] The next day 10,000 relatives and sympathizers gathered for a mass funeral and march shouting, ‘burn the Shah’, and ‘the Shah is the guilty one.’[94]

The fire helped to "kick protest into high gear." [95] and the number of demonstrators mushroomed to hundreds of thousands.[96]

[edit] Black Friday and its aftermath

By September, the nation was rapidly destabilizing, and major protests were becoming a regular occurrence. The Shah introduced martial law, and banned all demonstrations but on September 8 thousands of protesters gathered in Tehran. Security forces shot and killed dozens, in what became known as Black Friday.

The clerical leadership declared that "thousands have been massacred by Zionist troops,"[97] but in retrospect it has been said that "the main casualty" of the shooting was "any hope for compromise" between the protest movement and the Shah's regime.[98] The troops were actually ethnic Kurds who had been fired on by snipers, and post revolutionary tally by the Martyrs Foundation of people killed as a result of demonstrations throughout the city on that day found a total of 84 dead. [99] In the mean time however, the appearance of government brutality alienated much of the rest of the Iranian people and the Shah's allies abroad.

A general strike in October resulted in the paralysis of the economy, with vital industries being shut down, "sealing the Shah's fate".[100] By late summer 1978 the movement to overthrow had become "`viable` in the minds of many Iranians," boosting support that much more.[101] By autumn popular support for the revolution was so powerful that those who still opposed it became reluctant to speak out.[101] According to one source "victory may be dated to mid-November 1978."[101]

In an attempt to weaken Ayatollah Khomeini's ability to communicate with his supporters, the Shah urged Iraq to deport Khomeini. The Iraqi government cooperated and on October 3, Khomeini left Iraq for Kuwait, but was refused entry. Three days later he left for Paris and took up residence in the suburb of Neauphle-le-Château. Though farther from Iran, telephone connections with the home country and access to the international press were far better than in Iraq.[102]

[edit] Muharram protests

On December 2, during the Islamic month of Muharram, over two million people filled the streets of Tehran's Azadi Square (then Shahyad Square), to demand the removal of the Shah and return of Khomeini.[103]

A week later on December 10 and 11, a "total of 6 to 9 million" anti-shah demonstrators marched throughout Iran. According to one historian, "even discounting for exaggeration, these figures may represent the largest protest event in history." [104]

It is almost unheard of for a revolution to involve as much as 1 percent of a country's population. The French Revolution of 1789, the Russian Revolution of 1917, perhaps the Romanian Revolution of 1989 - these may have passed the 1 percent mark. Yet in Iran, more than 10% of the country marched in anti-shah demonstrations on December 10 and 11, 1978." [105]

By late 1978 the shah was in search of a prime minister and offered the job to a series of liberal oppositionists. While "several months earlier they would have considered the appointment a dream come true," they now "considered it futile".[106] Finally, in the last days of 1978, Dr. Shapour Bakhtiar, a long time opposition leader, accepted the post and was promptly expelled from the oppositional movement."

[edit] Victory of revolution and fall of monarchy

[edit] The Shah leaves

By mid-December the shah's position had deteriorated to the point were he "wanted only to be allowed to stay in Iran." He was turned down by the opposition. In late December, "he agreed to leave the country temporarily; still he was turned down." [107] On January 16, 1979 the Shah and the empress left Iran. Scenes of spontaneous joy followed and "within hours of almost every sign of the Pahlavi dynasty" was destroyed. [108]

Bakhtiar dissolved SAVAK, freed political prisoners, ordered the army to allow mass demonstrations, promised free elections and invited Khomeinists and other revolutionaries into a government of "national unity".[109] After stalling for a few days Bakhtiar allowed Ayatollah Khomeini to return to Iran, asking him to create a Vatican-like state in Qom and calling upon the opposition to help preserve the constitution.

[edit] Khomeini's return and fall of the monarchy

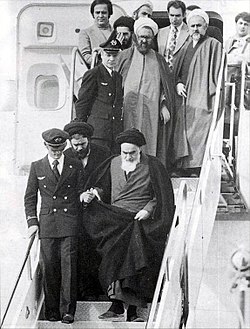

On February 1, 1979 Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Tehran in a chartered Air France Boeing 747.[110] The welcoming crowd of several million Iranians was so large he was forced to take a helicopter from the airport.[111] Khomeini was now not only the undisputed leader of the revolution,[112] he had become what some called a "semi-divine" figure, greeted as he descended from his airplane with cries of ‘Khomeini, O Imam, we salute you, peace be upon you.’[113] Crowds were now known to chant "Islam, Islam, Khomeini, We Will Follow You," and even "Khomeini for King."[114]

On the day of his arrival Khomeini made clear his fierce rejection of Bakhtiar's regime in a speech promising ‘I shall kick their teeth in.’

Khomeini appointed his own competing interim prime minister Mehdi Bazargan on February 4, `with the support of the nation’[115] and commanded Iranians to obey Bazargan as a religious duty.

[T]hrough the guardianship [Velayat] that I have from the holy lawgiver [the Prophet], I hereby pronounce Bazargan as the Ruler, and since I have appointed him, he must be obeyed. The nation must obey him. This is not an ordinary government. It is a government based on the sharia. Opposing this government means opposing the sharia of Islam ... Revolt against God's government is a revolt against God. Revolt against God is blasphemy.[116][117]

As Khomeini's movement gained momentum, soldiers began to defect to his side. On February 9 about 10 P.M. a fight broke out between loyal Immortal Guards and pro-Khomeini rebel Homafaran of Iran Air Force, with Khomeini declaring jihad on loyal soldiers who did not surrender.[118] Revolutionaries and rebel soldiers gained the upper hand and began to take over police stations and military installations, distributing arms to the public. The final collapse of the provisional non-Islamist government came at 2 p.m. February 11 when the Supreme Military Council declared itself "neutral in the current political disputes… in order to prevent further disorder and bloodshed."[119][120] Revolutionaries took over government buildings, TV and Radio stations, and palaces of Pahlavi dynasty.

This period, from February 1 to 11, is celebrated every year in Iran as the "Decade of Fajr."[121][122] February 11 is "Islamic Revolution's Victory Day", a national holiday with state sponsored demonstrations in every city.[123][124]

[edit] Consolidation of power by Khomeini

[edit] Conflicts amongst revolutionaries

With the fall of the shah, the glue that unified the various ideological (religious, liberal, secularist, Marxist, and Communist) and class (bazaari merchant, secular middle class, poor) factions of the revolution — opposition to the shah — was now gone.[125] Different interpretations of the broad goals of the revolution (an end to tyranny, more Islamic and less American and Western influence, more social justice and less inequality) and different interests, vyed for influence.

Some observers believe "what began as an authentic and anti-dictatorial popular revolution based on a broad coalition of all anti-Shah forces was soon transformed into an Islamic fundamentalist power-grab,"[126] that significant support came from Khomeini's non-theocratic allies who had thought he intended to be more a spiritual guide than a ruler[127] — Khomeini being in his mid-70s, having never held public office, been out of Iran for more than a decade, and having told questioners things like "the religious dignitaries do not want to rule."[128][129]

Another view is Khomeini had "overwhelming ideological, political and organizational hegemony,"[130] and non-theocratic groups never seriously challenged Khomeini's movement in popular support.[131]

In any case, Khomeini and his loyalists in the revolutionary organizations prevailed, making use of unwanted allies[132] (such as the Provisional Revolutionary Government) and with skillful timing eliminating both them and their adversaries from the political stage,[133] and implemented Khomeini's velayat-e faqih design for an Islamic Republic led by himself as Supreme Leader.[134]

[edit] Organizations of the revolution

The most important bodies of the revolution were the the Provisional Revolutionary Government (also Interim Government of Iran), headed by Khomeini-appointed Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan.[135] Operating separately were the Revolutionary Council made up of Khomeini and his clerical supporters, the Revolutionary Guards, Revolutionary Tribunals, Islamic Republican Party, and at the local level revolutionary cells turned local committees (komitehs).[136]

While the moderate Bazargan and his government (temporarily) reassured the middle class, it became apparent they did not have power over the "Khomeinist" revolutionary bodies, particularly the Revolutionary Council (the "real power" in the revolutionary state[137][138]) and later the Islamic Republican Party. Inevitably the overlapping authority of the Revolutionary Council (which had the power to pass laws) and Bazargan's government was a source of conflict,[139] despite the fact that both had been approved by and/or put in place by Khomeini.

This conflict lasted only a few months however as the provisional government fell shortly after American Embassy officials were taken hostage on November 4, 1979. Bazargan's resignation was received by Khomeini without complaint, saying "Mr. Bazargan ... was a little tired and preferred to stay on the sidelines for a while." Khomeini later described his appointment of Bazargan as a "mistake."[140]

The Revolutionary Guard, or Pasdaran-e Enqelab, was established by Khomeini on May 5, 1979 as a counterweight both to the armed groups of the left, and to the Iranian military, which had been part of the Shah's power base. 6,000 persons were initially enlisted and trained,[141] but the guard eventually grew into "a full-scale" military force. [142] It has been described as "without a doubt the strongest institution of the revolution"[143]

Serving under the Pasdaran were/are the "Oppressed Mobilization" or Baseej-e Mostaz'afin[144] volunteers originally made up of those too old or young[144] to serve in other bodies. Baseej have also been used to attack demonstrators and newspaper offices, they believe to be enemies of the revolution.[145]

Another revolutionary organization was the Islamic Republican Party started by Khomeini lieutenant Seyyed Mohammad Hosseini Beheshti in February 1979. Made up of Bzaari and political clergy, [146] it worked to establish theocratic government by velayat-e faqih in Iran outmaneuvering opponents and wielding power on the street through the Hezbollah.

The first komiteh or Revolutionary Committees "sprang up everywhere" as autonomous organizations in late 1978. After the monarchy fell the committees grew in number and power but not discipline.[147] In Tehran alone there were 1500 committees. Komiteh served as "the eyes and ears" of the new regime, and are credited by critics with "many arbitrary arrests, executions and confiscations of property".[148]

Also enforcing the will of the regime were the Hezbollahi (followers of the Party of God), "strong-arm thugs" who attacked demonstrators and offices of newspapers critical of Khomeini.[149]

Two major political groups formed after the fall of the shah that clashed with pro-Khomeini groups and were eventually supressed were the National Democratic Front, a somewhat more leftist version of the National Front (Iran), and the Muslim People's Republican Party, a competitor to the Islamic Republican Party that, unlike that body, favored pluralism, opposed summary executions and attacks on peaceful demonstations and was associated with Grand Ayatollah Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari.

[edit] Establishment of Islamic republic government

[edit] Referendum of 12 Farvardin

On March 30 and 31 (Farvardin 10, 11) a referendum was held over whether to replace the monarchy with an "Islamic Republic" — a term not defined on the ballot. Supporting the vote and the change were the Islamic Republican Party, Iran Freedom Movement, National Front, Muslim People's Republican Party, and Tudeh party. Urging a boycott were the National Democratic Front, Fadayan, and several Kurdish parties.[150] Khomeini called for a massive turnout and most Iranians supported the change.[150] Following the vote, the government announced that 98.2% had voted in favor[150] and Khomeini declaring the result a victory of "the oppressed ... over the arrogant."[151]

[edit] Writing of the constitution

In June 1979, the Freedom Movement released its draft constitution for the Islamic Republic that it had been working on while Khomeini was in exile. It included a Guardian Council to veto unIslamic legislation, but had no guardian jurist ruler.[152] Leftists had found too conservative and in need of major changes but Khomeini declared it `correct`.[153][129] To approve the new constitution a seventy-three-member Assembly of Experts for Constitution was elected that summer. Critics complained that "vote-rigging, violence against undesirable candidates and the dissemination of false information" was used to "produce an assembly overwhelmingly dominated by clergy loyal to Khomeini." [154]

The Assembly was originally conceived of as a way expediting the draft constitution which . Ironically, Khomeini (and the assembly) now rejected the constitution — its correctness notwithstanding — and Khomeini declaring that the new government should be based "100% on Islam."[155]

Between mid-August and mid-November 1979, the Assembly commenced to draw up a new constitution, one leftists found even more objectionable. In addition to president, the Assembly added on a more powerful post of guardian jurist ruler intended for Khomeini,[156] with control of the military and security services, and power to appoint several top government and judicial officials. The power and number of clerics on the Council of Guardians was increased. The council was given control over elections for president, parliament, and the "experts" that elected the Supreme Leader),[157] as well as laws passed by the legislature.

The new constitution was approved by referendum on December 2 and 3, 1979. It was supported by the Revolutionary Council and other groups, but opposed by some clerics, including Ayatollah Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari, and by secularists such as the National Front who urged a boycott. Again over 98% were reported to have voted in favor but turnout was smaller than on 11, 12 Farvardin.[158]

[edit] Hostage Crisis

A major turning point in the revolution that helped radicalize the revolution and undermined Iranian moderates was the holding of 52 American diplomats hostage for over a year. In late October 1979, the exiled and dying Shah was admitted into the United States for cancer treatment. In Iran there was an immediate outcry and both Khomeini and leftist groups demanding the Shah's return to Iran for trial and execution. On 4 November 1979 youthful Islamists, calling themselves Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line, invaded the embassy compound and seized its staff. Revolutionaries were reminded of how 26 years earlier the Shah had fled abroad while the American CIA and British intelligence organized a coup d'état to overthrow his nationalist opponent.

The holding of hostages was very popular and continued for months even after the death of the Shah. As Khomeini explained to his future President Bani-Sadr,

"This action has many benefits. ... This has united our people. Our opponents do not dare act against us. We can put the constitution to the people's vote without difficulty, and carry out presidential and parliamentary elections."[159]

With great publicity the students released documents from the American embassy — or "nest of spies" — by the students showing moderate Iranian leaders had met with U.S. officials (similar evidence of high ranking Islamists having done so did not see the light of day).[160] Among the causualties of the hostage crisis was Prime Minister Bazargan who resigned in November unable to enforce the government's order to release the hostages.[161]

The prestige of Khomeini and the hostage taking was further enhanced when an American attempt to rescue the hostages failed because of a sand storm, widely believed in Iran to be the result of divine intervention.[162] Another long-term effect of the crisis was on the Iranian economy which was subject to American economic sanctions still in place.[163][164]

[edit] Supression of opposition

In early March, Khomeini announced, "do not use this term, ‘democratic.’ That is the Western style," giving pro-democracy liberals (and later leftists) a taste of disappointments to come.[165]

In succession the National Democratic Front was banned in August 1979, the provisional goverment was disimpowered in November, the Muslim People's Republican Party banned in January 1980, the People's Mujahedin of Iran guerillas came under attack in February 1980, a purge of universities was begun in March 1980, and leftist Islamist Abolhassan Banisadr was impeached in June 1981.

[edit] Newspaper closings

In mid August, shortly after the election of the constitution-writing Assembly of Experts, several dozen newspapers and magazines opposing Khomeini's idea of Islamic government — theocratic rule by jurists or velayat-e faqih — were shut down[166][167] under a new press law banning "counter-revolutionary policies and acts." [168] Protests against the press closings were organized by the National Democratic Front (NDF). Khomeini angrily denounced these protests saying, "we thought we were dealing with human beings. It is evident we are not."[169]

He condemned the protesters as

`wild animals. We will not tolerate them any more ... After each revolution several thousand of these corrupt elements are executed in public and burnt and the story is over. They are not allowed to publish newspapers.`[170]

Hezbollah activists attacked the protesters and hundreds were injured by "rocks, clubs, chains and iron bars".[171] Before the end of the month a warrant was issued for the arrest of the NDF's leader.[172]

[edit] Muslim People's Republican Party

In December the moderate Islamic party Muslim People's Republican Party (MPRP), and its spiritual leader Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari had become a new rallying point for Iranians who wanted democracy not theocracy.[173] In early December riots broke out in Shariatmadari's Azeri home region. Members of the MPRP and Shariatmadari's followers in Tabriz took to the streets and seized the television station, using it to "broadcast demands and grievances." The regime reacted quickly, sending Revolutionary Guards to retake the TV station, mediators to diffuse complaints and staging a massive pro-Khomeini counter-demonstration in Tabriz. [174] The party was suppressed with many of the aides of the elderly Shariatmadari being put under house arrest.[175]

[edit] Islamist left

In January 1980 Abolhassan Banisadr, an adviser to Khomeini, was elected president of Iran. He was opposed by the more radical Islamic Republic party, who were also supported by Khomeini and who controlled the parliament having won the first parliamentary election of March-May 1980. Bani Sadr was compelled to accept an IRP-oriented prime minister, Mohammad-Ali Rajai, he declared "incompetent."[176]

At the same time, erstwhile revolutionary allies of the Khomeinists — the Islamist modernist guerrilla group People's Mujahedin of Iran (or MEK) — were being suppressed by Khomeinists. Khomeini attacked the MEK as elteqati (eclectic), contaminated with Gharbzadegi ("the Western plague"), and as monafeqin (hypocrits) and kafer (unbelievers).[177] In February 1980 concentrated attacks by hezbollahi toughs began on the meeting places, bookstores, newsstands of Mujahideen and other leftists[178] driving the left underground in Iran.

The next month saw the begining of the "Cultural Revolution". Universities, a leftist bastion, were closed for two years to purge them of opponents to theocratic rule. A purge of the state bureaucracy began in July. 20,000 teachers and nearly 8,000 military officers deemed too "Westernized" were dismissed.[179]

Khomeini sometimes felt the need to use takfir (declaring someone guilty of apostasy, a capital crime) to deal with his opponents. When leaders of the National Front party called for a demonstration in mid-1981 against a new law on qesas, or traditional Islamic retaliation for a crime, Khomeini threatened its leaders with the death penalty for apostasy "if they did not repent."[180]

By March 1981, an attempt by Khomeini to forge a reconciliation between Bani-Sadr and IRP leaders had failed[181] and Bani Sadr became a rallying point "for all doubters and dissidents" of the theocracy, including the MEK.[182] Three months later Khomeini finally sided with the Islamic Republic party and Bani Sadr issued a call for "resistance to dictatorship". Rallies in favor of Bani Sadr were suppressed by Hezbollahi and he was impeached by the Majlis.

The MEK retaliated with a campaign of terror against the IRP. On the 28 June 1981, a bombing of the office of the Islamic Republic Party killed around 70 high-ranking officials, cabinet members and members of parliament, including Mohammad Beheshti, the secretary-general of the party and head of the Islamic Party's judicial system.[183] His successor Mohammad Javad Bahonar was in turn assassinated on September 2.[184] These events and other assassinations weakened the Islamic Party[146] but the hoped-for mass uprising and armed struggle against the Khomeiniists was crushed.

Other opposition to the Khomeinist regime was violent as well. Communist guerrillas and federalist parties revolted in some regions comprising Khuzistan, Kurdistan and Gonbad-e Qabus which resulted in fighting among them and revolutionary forces. These revolts began in April and lasted for several months or years depending on the region.

[edit] Casualties and opposition

[edit] Casualties of the monarchy

Estimates of casualties suffered during the Iranian Revolution differ widely, at least between the Islamic government and Western-based hsitorians. Ayatollah Khomeini stated that "60,000 men, women and children were martyred by the Shah's regime,"[185] and this number appears in the introduction of the constitution of the Islamic Republic.[186]

More recently, estimates by researcher at the Martyrs Foundation (Bonyad Shahid), Emad al-Din Baghi, [187] compiled a far lower number of casualties - 2,781 killed in the 1978 and 1979 clashes between demonstrators and the Shah's army and security forces.[185][188] The Martyrs Foundation, established in Iran after the revolution to compensate the survivors of fallen revolutionaries, could identify only 744 martyrs in Tehran, where the majority of the casualties were supposed to have occurred.[189].

These number are not accepted in the Islamic Republic but used by historians in the west and mean that Iran suffered remarkably few casualties compared to contemporary events such as the South African anti-apartheid movement[190].

[edit] Casualties of the Islamic government

After the fall of the monarchy the first to be executed by revolutionary leadership were members of the old regime: first senior generals, and over the next couple of months over 200 of the Shah's senior civilian officials[191] as punishment and to eliminate the danger of coup d’État. Brief trials lacking defense attorneys, juries, transparency or opportunity for the accused to defend themselves[192] were held by revolutionary judges such as Sadegh Khalkhali, the Sharia judge. By January 1980 "at least 582 persons had been executed."[193] Among those executed was Amir Abbas Hoveida, former Prime Minister of Iran. Between January 1980 and June 1981, when Bani-Sadr was impeached, at least 900 executions took place,[194] for everything from drug and sexual offenses to `corruption on earth,` from plotting counter-revolution and spying for Israel to membership in opposition groups.[195] In the 12 months following that Amnesty International documented 2,946 executions, with several thousand more dead from executions, in street battles, or under torture in the next two years according to the anti-regime guerillas People's Mujahedin of Iran. [196]

[edit] Impact of the Revolutionary

[edit] Neighboring regimes and the Iran–Iraq War

The Islamic Republic positioned itself as a revolutionary beacon under the slogan "neither East nor West" (i.e. follow neither Soviet nor American/West European models), and called for the overthrow of capitalism, American influence, and social injustice in the Middle East and the rest of the world. Revolutionary leaders in Iran gave and sought support from non-Islamic as well as Islamic Third World causes — e.g. the PLO, Sandinistas in Nicaragua, Irish IRA and anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa — even to the point of favoring non-Muslim revolutionaries over more conservative Islamic causes such as the neighboring Afghan Mujahideen.[197]

In its region, Iranian Islamic revolutionaries called specifically for the overthrow of monarchies and their replacement with Islamic republics, much to the alarm of its smaller Sunni-run Arab neighbors Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the other Persian Gulf States. Most of these countries were monarchies and all had sizable Shi'a populations — including a majority population in Iraq and Bahrain. In 1980, Iraq, whose government was Sunni Muslim and Arab nationalist, invaded Iran in an attempt to seize the oil-rich predominantly Arab province of Khuzistan and destroy the revolution in its infancy. Thus began the eight year Iran–Iraq War, one of the most destructive and bloody wars of the 20th century.

A combination of fierce patriot resistance by Iranians and military incompetence by Iraqi forces soon stalled the Iraqi advance, and by early 1982 Iran regained almost all the territory lost to the invasion. The invasion rallied Iranians behind the new regime, and past differences were largely abandoned in the face of the external threat. The war also served as an opportunity for the regime to crush its remaining opponents, mostly the Soviet-backed leftist groups, dishing out harsh treatment, including torture and imprisonment.

Realizing its mistake, the Iraqis offered Iran a truce. Khomeini rejected it, announcing the only condition for peace was that "the regime in Baghdad must fall and must be replaced by an Islamic Republic."[198] The war continued for another six years under the slogans `War, War until Victory,` and `The Road to Jerusalem Goes through Baghdad,`[199] but ultimately ended in a truce with no Islamic revolutution in Iraq. Hundreds of thousands of lives lost and destruction from air attacks was a result but the war did solidify the revolution in Iran.[200]

[edit] Western/U.S.-Iranian relations

[edit] International

Internationally, the initial impact of the Islamic revolution was immense. In the non-Muslim world it has changed the image of Islam, generating much interest in the politics and spirituality of Islam.[201] In 1980, the American magazine TIME speculated that the revolution threatened "to upset the world balance of power more than any political event since Hitler's conquest of Europe." [202]

In the Mideast and Muslim world, particularly in its early years, it triggered enormous enthusiasm and redoubled opposition to western intervention and influence. Islamist insurgents rose in Saudi Arabia (the 1979 week-long takeover of the Grand Mosque), Egypt (the 1981 assassination of the Egyptian President Sadat), Syria (the Muslim Brotherhood rebellion in Hama), and Lebanon (the 1983 bombing of the American Embassy and French and American peace-keeping troops).[203]

Although ultimately these rebellions did not succeed, other activities have had more long term impact. The Ayatollah Khomeini's 1989 fatwa calling for the killing of Salman Rushdie for his allegedly blasphemous book The Satanic Verses, demonstrated that even citizens of a foreign country living in that country were not safe from the long arm of the Islamic revolution. The Islamic revolutionary government itself is credited with helping establish Hezbollah in Lebanon as a major political and military power, fighting successfully against Israeli occupation and its proxy South Lebanon Army, and expanded Shia Islam's influence.[204] Other groups the Islamic revolutionary government is credited with financing and helping create include the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq and the United Islamic Front for the Salvation of Afghanistan.

On the minus side, at least one observer argues that despite great effort and expense the only country outside Iran the revolution had a "measure of lasting influence" on prior to the 2003 invasion of Iraq was Lebanon.[205] Others claim the devastating Iran–Iraq War "mortally wounded ... the ideal of spreading the Islamic revolution,"[206] or that Iran has weakened "its place as a great regional power,"[207] because the ideology of the revolution prevents Iran from following a "nationalist, pragmatic" foreign policy.

[edit] Domestic

Internally, the revolution has brought a broadening of education and health care for the poor, and particularly governmental promotion of Islam, and the elimination of secularism and American influence in government, but not greater political freedom, governmental honesty and efficiency, economic equality and self-sufficiency, or even popular religious devotion.[208][209][210] Opinion polls and observers report widespread dissatisfaction, including a "rift" between the revolutionary generation and younger Iranians who find it "impossible to understand what their parents were so passionate about."[211]

[edit] Human development

Literacy has increased. The Islamic Republic established a Literacy Movement Organization (LMO), based on Islamic principles, [212] (replacing the Shah's popular and successful Literacy Corps).[213] By 2002 illiteracy rates dropped by more than half.[214][215][216] Maternal and infant mortality rates have also been cut significantly.[217] Population growth was first encouraged, but discouraged after 1988.[218] Overall, Iran's Human development Index rating has climbed significantly from 0.569 in 1980 to 0.732 in 2002, on par with neighbour Turkey.[219][220]

[edit] Politics and government

Iran has elected governmental bodies at the national, provincial and local levels for which all males and females from the age of 18 on up may vote. (See Politics and Government of Iran) Although these bodies are subordinate to theocracy — which has veto power over who can run for parliament (or Islamic Consultative Assembly) and whether its bills can become law — they have more power than equivalent organs in the Shah's government. While Iran's small non-Muslim minorities do not have equal rights and some complain of discrimination, five of the 290 parliamentary seats are allocated to their communities (3 seats for Christians, one for Jews and one for Zoroastrians) [221][222] Most minorities also benefited from a fatwa decreed by Khomeini early in the revolution decreeing their protection.[223]

Definitely not protected have been members of the Bahá'í Faith, which has been declared heretical and subversive. More than 200 Bahá'ís have been executed or killed, hundreds more have been imprisoned, and tens of thousands have been deprived of jobs, pensions, businesses, and educational opportunities. Bahá'í administrative structures have been banned, holy places confiscated, vandalized, or destroyed.[224]

Whether the Islamic Republic has brought more or less severe political repression is disputed. Grumbling once done about the tyranny and corruption of the Shah and his court is now directed against "the Mullahs."[225] Fear of SAVAK has been replaced by fear of Revolutionary Guards, and other religious revolutionary enforcers.[226] Violations of human rights by the theocratic regime is said by some to be worse than during the monarchy,[227] and in any case extremely grave.[228] Reports of torture, imprisonment of dissidents, and the murder of prominent critics have been made by human rights groups. Censorship is handled by the Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance, without whose official permission, "no books or magazines are published, no audiotapes are distributed, no movies are shown and no cultural organization is established."[229]

[edit] Women

Observers were struck by the large scale participation of women — most from traditional backgrounds — in revolutionary demonstrations.[230] Female university enrollment has risen steadily following the revolution,[231] (though this is a cause of alarm by regime authorities).[232][233] There are large numbers of women in the civil service and higher education, and several women have been elected to the Iranian parliament.

Nonetheless the ideology of the revolution opposes equal rights for women. Within months of the founding of the Islamic Republic the 1967 Family Protection Law was repealed, female government workers were forced to observe Islamic dress code, women were barred from becoming judges, beaches and sports were sex-segregated, the marriage age for girls was reduced to 13 and married women were barred from attending regular schools.[234] Women began almost immediately to protest[235][236] and have won some reversals of policies in the years hence. Inequality for women in inheritance and other areas of the the civil code remain. Segregation of the sexes, from "schoolrooms to ski slopes to public buses", is strictly enforced. Females caught by revolutionary officials in a mixed-sex situation can be subject to virginity tests.[237] "Bad hijab" ― exposure of any part of the body other than hands and face — is subject to punishment of up to 70 lashes or 60 days imprisonment.[238][239]

[edit] Economy

Iran's economy has not prospered. Dependence on petroleum exports is still strong.[240] Per capita income fluctuates with the price of oil — reportedly falling at one point to 1/4 of what it was prior to the revolution[241][242] and has still not reached pre-revolution levels. Unemployment among Iran's population of young has steadily risen as job creation has failed to keep up,[243] a high level of corruption being blamed in part.[244][243] Problems manifest themselves in international travel, were one Iranian complained to an expatriate journalist: "What has come of us. Our currency is worthless. Those backward Arabs go to Europe with rials, and we can barely visit Turkey with our worthless tomans!"[245]

Gharbzadegi ("westoxification") or western cultural influence stubbornly remains, brought by music recordings, videos, and satellite dishes.[246] One post-revolutionary opinion poll found 61% of students in Tehran chose "Western artists" as their role models with only 17% choosing "Iran's officials."[247]

[edit] See also

- History of Iran

- Ruhollah Khomeini

- History of the Islamic Republic of Iran

- Hokumat-e Islami : Velayat-e faqih (book by Khomeini)

- 1979 energy crisis

- Guerrilla groups of Iran

- History of political Islam in Iran

- Human rights in Islamic Republic of Iran

- Iran hostage crisis

- People's Mujahedin of Iran

- Persecution of Bahá'ís

- Persian Constitutional Revolution

- Timeline of Iranian revolution

- White Revolution

- Wilayat al-Faqih

- Organizations of the Iranian Revolution

[edit] References and notes

- ^ Islamicaaaa Revolution, Iran Chamber.

- ^ Islamic Revolution of Iran, MS Encarta.

- ^ The Islamic Revolution, Internews.

- ^ Iranian Revolution.

- ^ Iran Profile, PDF.

- ^ The Shah and the Ayatollah: Iranian Mythology and Islamic Revolution (Hardcover), ISBN 0-275-97858-3, by Fereydoun Hoveyda, brother of Amir Abbas Hoveyda.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Nasr, Vali, The Shia Revival, Norton, (2006), p.121

- ^ The Iranian Revolution

- ^ Ruhollah Khomeini, Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Iran Islamic Republic, Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Amuzegar, The Dynamics of the Iranian Revolution, (1991), p.4, 9-12

- ^ Arjomand, Turban (1988), p. 191.

- ^ Amuzegar, Jahangir, The Dynamics of the Iranian Revolution, SUNY Press, p.10

- ^ Kurzman, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, (2004), p.121

- ^ Harney, Priest (1998), p. 2.

- ^ Abrahamian Iran (1982), p. 496.

- ^ Benard, "The Government of God" (1984), p. 18.

- ^ Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, "As Soon as Iran Achieves Advanced Technologies, It Has the Capacity to Become an Invincible Global Power," 9/28/2006 Clip No. 1288.

- ^ Shirley, Know Thine Enemy (1997), pp. 98, 104, 195.

- ^ Akhbar Ganji talking to Afshin Molavi. Molavi, Afshin, The Soul of Iran, Norton paperback, (2005), p.156.

- ^ {{cite journal |last= Del Giudice |first= Marguerite |year=2008 |month= August |title= Persia: Ancient Soul of Iran|journal= [[National Geographic|accessdate=2009-01-28}}

- ^ Brumberg, Reinventing Khomeini (2001).

- ^ Shirley, Know Thine Enemy (1997), p. 207.

- ^ a b Harney, The Priest (1998), pp. 37, 47, 67, 128, 155, 167.

- ^ Iran Between Two Revolutions by Ervand Abrahamian, p.437

- ^ Mackay, Iranians (1998), pp. 236, 260.

- ^ Graham, Iran (1980), pp. 19, 96.

- ^ Graham, Iran (1980) p. 228.

- ^ Arjomand, Turban (1998), pp. 189–90.

- ^ Kurzman, Charles, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, Harvard University Press, 2004, p.111

- ^ Taheri, The Spirit of Allah (1985), p. 238.

- ^ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p. 178.

- ^ Hoveyda Shah (2003) p. 22.

- ^ Abrahamian, Iran (1982), pp. 533–4.

- ^ Schirazi, The Constitution of Iran (1997), pp. 293–4.

- ^ http://www.worldstatesmen.org/Iran_const_1906.doc

- ^ Mackey, The Iranians, (1996) p.184

- ^ Bakhash, Shaul, Reign of the Ayatollahs : Iran and the Islamic Revolution by Shaul, Bakhash, Basic Books, c1984 p.22

- ^ Taheri, Amir, The Spirit of Allah : Khomeini and the Islamic Revolution, Adler and Adler, c1985, p.94-5

- ^ Rajaee, Farhang, Islamic Values and World View: Farhang Khomeyni on Man, the State and International Politics, Volume XIII (PDF), University Press of America. ISBN 0-8191-3578-X

- ^ Nehzat by Ruhani vol. 1 p. 195, quoted in Moin, Khomeini (2000), p. 75.

- ^ Islam and Revolution, p. 17.; Later, much lower estimates of 380 dead can be found in Moin, Baqer, Khomeini: Life of the Ayatolla, (2000), p. 112.

- ^ Graham, Iran 1980, p. 69.

- ^ a b Mackay, Iranians (1996) pp. 215, 264–5.

- ^ Keddie, Modern Iran, (2003) p.201-7

- ^ The Last Great Revolution Turmoil and Transformation in Iran, by Robin WRIGHT.

- ^ Dabashi, Theology of Discontent (1993), p.419, 443

- ^ Khomeini; Algar, Islam and Revolution, p.52, 54, 80

- ^ See: Velayat-e faqih (book by Khomeini)#Importance_of_Islamic_Government

- ^ khomeinism

- ^ Abrahamian, Ervand, Khomeinism : Essays on the Islamic Republic, Berkeley : University of California Press, c1993. p.30,

- ^ See: Hokumat-e Islami : Velayat-e faqih (book by Khomeini)#Why_Islamic_Government_has_not_been_established

- ^ Khomeini and Algar, Islam and Revolution (1981), p.34

- ^ Taheri, The Spirit of Allah (1985), p. 196.

- ^ Graham, Iran (1980), p. 213.

- ^ Hiro, Dilip. Iran Under the Ayatollahs. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. 1985. p. 57.

- ^ Wright, Last (2000), p. 220.

- ^ Graham, Iran (1980) p. 94.

- ^ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p. 174.

- ^ Graham, Iran (1980), p. 96.

- ^ Abrahamian, Iran (1982), p. 444.

- ^ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p. 163.

- ^ Graham, Iran (1980), p. 226.

- ^ Abrahamian, Iran (1982), pp. 501–3.

- ^ Moin, Khomeini (2000), pp. 183–4.

- ^ Moin, Khomeini (2000), pp. 184–5.

- ^ Taheri, Spirit (1985), pp. 182–3.

- ^ Abrahamian, Iran Between (1980), pp. 502–3.

- ^ Mackay, Iranians (1996), p. 276.

- ^ Abrahamian, Iran Between (1980), pp. 478–9

- ^ "Ideology, Culture, and Ambiguity: The Revolutionary Process in Iran", Theory and Society, Vol. 25, No. 3 (Jun., 1996), pp. 349–88.

- ^ Kurzman, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, (2004), p.145-6

- ^ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p.80

- ^ Kurzman, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, HUP, 2004, p.164

- ^ Kurzman, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, HUP, 2004, p.137

- ^ Abrahamian, Iran (1982), p. 505.

- ^ Kurzman, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, HUP, 2004, p.38

- ^ Mackey, Iranians (1996) p. 279.

- ^ Harney, The Priest (1998), p. 14.

- ^ Abrahamian, Iran (1982), pp. 510, 512, 513.

- ^ Abrahamian, Iran (1982), p. 498–9.

- ^ Carter, Jimmy, Keeping the Faith: Memoirs of a president, Bantam, 1982, p.438

- ^ a b Keddie, Modern Iran (2003), p. 235.

- ^ Keddie, Modern Iran (2003), pp. 235–6.

- ^ Shawcross, The Shah's Last Ride (1988), p. 21.

- ^ Kurzman, Charles, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, Harvard University Press, 2004, p.157

- ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Causes_of_the_Iranian_Revolution#Failures_and_successes_of_foreign_forces

- ^ Amuzegar, Jahangir, Dynamics of Iranian Revolution: The Pahlavis' Triumph and Tragedy SUNY Press, (1991) p.4, 21, 87

- ^ Kurzman, Charles, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, Harvard University Press, 2004, p.51

- ^ Taheri, Spirit (1985) p. 220.

- ^ In a recent book by Hossein Boroojerdi, called "Islamic Revolution and its roots", he claims that Cinema Rex was set on fire using chemical material provided by his team operating under the supervision of "Hey'at-haye Mo'talefe (هیأتهای مؤتلفه)", an influential alliance of religious groups who were among the first and most powerful supporters of Ayatollah Khomeini.

- ^ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p. 187.

- ^ W. Branigin, ‘Abadan Mood Turns Sharply against the Shah,’ Washington Post, 26, August 1978

- ^ Kurzman, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, (2004), p.61

- ^ Kurzman, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, (2004), p.117

- ^ Taheri, The Spirit of Allah (1985), p. 223.

- ^ Abrahamian, Ervand, History of Modern Iran, Cambridge University Press, 2008, p.160-1

- ^ The Martyrs Foundation compensates families of victims and compiled a list of "martyrs" of the revolution. [E. Baqi, `Figures for the Dead in the Revolution`, Emruz, 30 July 2003, quoted in Abrahamian, Ervand, History of Modern Iran, Cambridge University Press, 2008, p.160-1

- ^ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p. 189.

- ^ a b c Kurzman, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, (2004), p.137

- ^ History of Iran: Ayatollah Khomeini

- ^ Abrahamian, Iran: Between Two Revolutions (1982), pp. 521–2.

- ^ Kurzman, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, (2004), p.122

- ^ Kurzman, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, (2004), p.121

- ^ Kurzman, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, (2004), p.144

- ^ Kurzman, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, (2004), p.154

- ^ Taheri, Spirit (1985), p. 240.

- ^ "Demonstrations allowed", ABC Evening News for Monday, January 15, 1979.

- ^ The Khomeini Era Begins - TIME

- ^ Abrahamian, Ervand, History of Modern Iran, Cambridge University Press, 2008, p.161

- ^ Taheri, Spirit (1985), p. 146.

- ^ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p. 200.

- ^ What Are the Iranians Dreaming About? by Michel Foucault, Chicago: University Press.

- ^ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p. 204.

- ^ Khomeini, Sahifeh-ye Nur, vol.5, p.31, translated by Baqer Moin in Khomeini (2000), p.204

- ^ چرا و چگونه بازرگان به نخست وزیری رسید؟ The commandment of Ayatollah Khomeini for Bazargan and his sermon on February 5.

- ^ Moin, Khomeini (2000), pp. 205–6.

- ^ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p. 206.

- ^ Abrahamian, Iran (1982), p. 529.

- ^ Adnki.

- ^ Iran 20th, 1999-01-31, CNN World.

- ^ RFERL.

- ^ Iran Anniversary, 2004-02-11, CBC World.

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, 2002, p.112

- ^ Zabih, Sepehr, Iran Since the Revolution Johns Hopkins Press, 1982, p.2

- ^ Schirazi, Constitution of Iran, (1997), p.93-4

- ^ "Democracy? I meant theocracy", by Dr. Jalal Matini, translation & introduction by Farhad Mafie, August 5, 2003, The Iranian.

- ^ a b Islamic Clerics, Khomeini Promises Kept, Gems of Islamism.

- ^ Azar Tabari, ‘Mystifications of the Past and Illusions of the Future,’ in The Iranian Revolution and the Islamic Republic: Proceedings of a Conference, ed. Nikki R. Keddie and Eric Hooglund (Washington DC: Middle East Institute, 1982) pp. 101–24.

- ^ For example, Islamic Republic Party and allied forces controlled approximately 80% of the seats on the Assembly of Experts of Constitution. (see: Bakhash, Reign of the Ayatollahs (1983) p.78-82) An impressive margin even allowing for electoral manipulation

- ^ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p.224

- ^ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p. 203.

- ^ Schirazi, Constitution of Iran, (1997), pp. 24–32.

- ^ Moin, Khomeini, 2000, p. 203

- ^ Keddie, Modern Iran (2003), pp. 241–2.

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, (2001), p.

- ^ Arjomand, Turban for the Crown, (1988) p.135)

- ^ Keddie, Modern Iran (2003) p.245

- ^ Moin, Khomeini,(2000), p.222

- ^ Baskhash, Reign of the Ayatollahs, (1984) p.63

- ^ Mackey, Iranians (1996), p.371

- ^ Schirazi, Constitution of Iran, (1997) p.151

- ^ a b Niruyeh Moghavemat Basij - Mobilisation Resistance Force

- ^ Keddie, Modern Iran, (2003) p.275

- ^ a b Moin, Khomeini (2000), p.210-1

- ^ Bakhash, Reign of the Ayatollahs, (1984), p.56

- ^ Moin, Khomeini (2000) p.211

- ^ Schirazi, Constitution of Iran, (1987)p.153

- ^ a b c Bakhash, Shaul, Reign of the Ayatollahs, (1984) p.73

- ^ 12 Farvardin

- ^ Moin, Khomeini, 2000, p. 217.

- ^ Schirazi, The Constitution of Iran, 1997, p. 22–3.

- ^ Moin, Khomeini, (2001), p.218

- ^ Bakhash, Shaul, The Reign of the Ayatollahs, Basic Books, 1984 p.74-82

- ^ [1]

- ^ Articles 99 and 108 of the constitution

- ^ History of Iran: Iran after the victory of 1979's Revolution

- ^ Moin, Khomeini, (2000), p.228

- ^ Moin, Khomeini, (2000), p.248-9

- ^ Keddie, Modern Iran (2003), p.249

- ^ Bowden, Mark, Guests of the Ayatollah, Atlantic Monthly Press, 2006, p.487

- ^ Bakhash, Reign of the Ayatollahs, (1984), p.236

- ^ Brumberg, Daniel Reinventing Khomeini, university of Chicago Press, (2001), p.118

- ^ Bakhash, Shaul, The Reign of the Ayatollahs, p. 73.

- ^ Schirazi, Constitution of Iran (1997) p. 51.

- ^ Moin, Khomeini, 2000, pp. 219–20.

- ^ Kayhan, 20.8.78-21.8.78,` quoted in Schirazi, Asghar, The Constitution of Iran, Tauris, 1997, p.51, also New York Times, August 8, 1979

- ^ Moin, Khomeini, 2000, p. 219.

- ^ Moin, Khomeini, (2001), p.219

- ^ Moin, Khomeini, (2001), p.219-20

- ^ Bakhash, The Reign of the Ayatollahs (1984) p.89.

- ^ Moin, Khomeini, 2000, p. 232.

- ^ Bakhash, The Reign of the Ayatollahs, (1984) p.89-90

- ^ Moin, Khomeini, 2000, p. 232.

- ^ Moin, Khomeini, 2001, p.234-5

- ^ Moin Khomeini, 2001, p.234, 239

- ^ Bakhash, The Reign of the Ayatollahs, (1984) p. 123.

- ^ Arjomand, Said Amir, Turban for the Crown: The Islamic Revolution in Iran, Oxford University Press, 1988 p. 144.

- ^ Schirazi, Asghar, The Constitution of Iran, Tauris 1997, p. 127.

- ^ Bakhash, The Reign of the Ayatollahs, (1984) p.153

- ^ Moin Khomeini, 2001, p.238

- ^ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p. 241–2.

- ^ Iran Backgrounder, HRW.

- ^ a b A Question of Numbers Web: IranianVoice.org August 08, 2003 Rouzegar-Now Cyrus Kadivar

- ^ The Constitution of Islamic Republic of Iran. THE PRICE THE NATION PAID

- ^ Emad al-Din Baghi is no longer a researcher at Bonyad Shahid.

- ^ E. Baqi, `Figures for the Dead in the Revolution`, Emruz, 30 July 2003

- ^ Kurzman, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, (2004), p.71

- ^ in South Africa hundreds of suspected traitors of the cause were killed with `necklaces` of burning tires, and there were more than 7000 revolutionary martyrs, Kurzman, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, (2004), p.71

- ^ Moin, Khomeini, 2000, p. 208.

- ^ Bakhash, The Reign of the Ayatollahs (1984), p. 61.

- ^ Mackey, Iranians (1996) p.291

- ^ Source: Letter from Amnesty International to the Shaul Bakhash, 6 July 1982. Quoted in The Reign of the Ayatollahs by Shaul Bakhash, p.111

- ^ The Reign of the Ayatollahs by Shaul Bakhash, p.111

- ^ The Reign of the Ayatollahs by Shaul Bakhash, p.221-222

- ^ Roy, Failure of Political Islam (1994), p. 175.

- ^ Wright, In the Name of God (1989), p. 126.

- ^ Abrahamian, History of Modern Iran, (2008) p.175

- ^ Expansion of the Islamic Revolution and the War with Iraq, Gems of Islamism.

- ^ Shawcross, William, The Shah's Last Ride (1988), p. 110.

- ^ The Mystic Who Lit The Fires of Hatred, Jan. 7, 1980

- ^ Fundamentalist Power, Martin Kramer.

- ^ Harik, Judith Palmer, Hezbollah, the Changing Face of Terrorism (2004), 40

- ^ Nasr, Vali, The Shia Revival Norton, (2006), p.141

- ^ Keddie, Modern Iran (2003) p.241

- ^ Roy, Failure of Political Islam (1994), p. 193.

- ^ Roy, Failure of Political Islam (1994), p. 199.

- ^ Iran "has the lowest mosque attendance of any Islamic country." according to of the revolution

- ^ Khomeini Promises Kept, Gems of Islamism.

- ^ A Revolution Misunderstood

- ^ Iran, the UNESCO EFA 2000 Assessment: Country Reports.

- ^ Iran, the Essential Guide to a Country on the Brink, Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2006, p.212

- ^ National Literacy Policies, Islamic Republic of Iran

- ^ Adult education offers new opportunities and options to Iranian women, UNGEI.

- ^ Adult education offers new opportunities and options to Iranian women, UNFPA.

- ^ Howard, Jane. Inside Iran: Women's Lives, Mage publishers, 2002, p.89

- ^ Keddie, Modern Iran (2003) p.287-8

- ^ Iran: Human Development Index

- ^ Turkey: Human Development Index

- ^ Constitution, Iran Online.

- ^ WRIGHT, The Last Great Revolution, NY Times Books.

- ^ IRAN: Life of Jews Living in Iran

- ^ ADL Says Iranian Attempt to Monitor Bahais Sets 'Dangerous Precedent', ADL.

- ^ Shirley, Know Thine Enemy (1997)

- ^ Schirazi, Constitution of Iran, 1997, p. 153.

- ^ "Ganji: Iran's Boris YELTSIN," by Amir Taheri, Arab News July 25, 2005

- ^ Backgrounder, HRW.

- ^ Naghmeh Zarbafian in My Sister, Guard Your Veil, My Brother, Guard Your Eyes (2006), (p.63)

- ^ Graham Iran (1980) p. 227.

- ^ it reached 66% in 2003. (Keddie,Modern Iran (2003) p.286)

- ^ Women graduates challenge Iran, Francis Harrison, BBC, September 26, 2006; accessed September 21, 2008.

- ^ Iran: Does Government Fear Educated Women?, Iraj Gorgin, Radio Free Europe, February 10, 2008; accessed September 21, 2008.

- ^ Chronology of Events Regarding Women in Iran since the Revolution of 1979, Elham Gheytanchi, Social Research via FindArticles, Summer 2000; accessed September 21, 2008.

- ^ The Unfinished Revolution, Time Magazine, April 2, 1979; accessed September 21, 2008.

- ^ [2], Nikki R. Keddie, Social Research via FindArticles.com, Summer 2000; accessed September 21, 2008.

- ^ Wright, The Last Great Revolution, (2000), p.136.

- ^ Wright, The Last Great Revolution (2000), p.136.

- ^ [3] Video: `Iranian Police Enforces "Islamic Dress Code" on Women in the Streets of Tehran,` April 15, 2007

- ^ Keddie, Modern Iran, (2003), p.271.

- ^ Low reached in 1995, from: Mackey, Iranians, 1996, p. 366.

- ^ "According to World Bank figures, which take 1974 as 100, per capita GDP went from a high of 115 in 1976 to a low of 60 in 1988, the year war with Iraq ended ..." (Keddie, Modern Iran, 2003, p.274)

- ^ a b "Still failing, still defiant", Economist, December 9, 2004.

- ^ "Iran: Bribery and Kickbacks Persists Despite Anti-Corruption Drive." Global Information Network, July 15, 2004 p. 1.

- ^ Molavi, Afshin, The Soul of Iran, Norton, (2005), p.18

- ^ Culture, Khomeini Promises Kept, Gems of Islamism.

- ^ ‘Political Inclinations of the Youth and Students,’ Asr-e Ma, n.13, 19 April 1995 in Brumberg, Reinventing Khomeini (2001), pp. 189–90.

[edit] Bibliography

- Amuzgar, Jahangir (1991). The Dynamics of the Iranian Revolution: The Pahlavis' Triumph and Tragedy: 31.. SUNY Press.

- Arjomand, Said Amir (1988). Turban for the Crown: The Islamic Revolution in Iran. Oxford University Press.

- Abrahamian, Ervand (1982). Iran between two revolutions. Princeton University Press.

- Bakhash, Shaul (1984). Reign of the Ayatollahs''. Basic Books,.

- Benard, Cheryl and Khalilzad, Zalmay (1984). "The Government of God" — Iran's Islamic Republic. Columbia University Press.

- Graham, Robert (1980). Iran, the Illusion of Power. St. Martin's Press.

- Harney, Desmond (1998). The priest and the king: an eyewitness account of the Iranian revolution. I.B. Tauris.

- Harris, David (2004). The Crisis: the President, the Prophet, and the Shah — 1979 and the Coming of Militant Islam. Little, Brown.

- Hoveyda, Fereydoun (2003). The Shah and the Ayatollah: Iranian mythology and Islamic revolution. Praeger.

- Kapuscinski, Ryszard (1985). Shah of Shahs. Harcourt Brace, Jovanovich.

- Keddie, Nikki (2003). Modern Iran: Roots and Results of Revolution. Yale University Press.

- Kepel, Gilles (2002). The Trail of Political Islam. Harvard University Press.

- Mackey, Sandra (1996). The Iranians: Persia, Islam and the Soul of a Nation. Dutton.

- Miller, Judith (1996). God Has Ninety Nine Names. Simon & Schuster.

- Moin, Baqer (2000). Khomeini: Life of the Ayatollah. Thomas Dunne Books.

- Roy, Olivier (1994). The Failure of Political Islam. Harvard University Press.

- Ruthven, Malise (2000). Islam in the World. Oxford University Press.

- Schirazi, Asghar (1997). The Constitution of Iran. Tauris.

- Shirley, Edward (1997). Know Thine Enemy. Farra.

- Taheri, Amir (1985). The Spirit of Allah. Adler & Adler.

- Wright, Robin (2000). The Last Great Revolution: Turmoil And Transformation In Iran. Alfred A. Knopf: Distributed by Random House.

- Zabih, Sepehr (1982). ''Iran Since the Revolution. Johns Hopkins Press.

- Zanganeh, Lila Azam (editor) (2006). My Sister, Guard Your Veil, My Brother, Guard Your Eyes : Uncensored Iranian Voices. Beacon Press.

[edit] Further reading

- Afshar, Haleh, ed. (1985). Iran: A Revolution in Turmoil. Albany: SUNY Press. ISBN 0-333-36947-5.

- Barthel, Günter, ed. (1983). Iran: From Monarchy to Republic. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

- Daniel, Elton L. (2000). The History of Iran. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-30731-8.

- Esposito, John L., ed. (1990). The Iranian Revolution: Its Global Impact. Miami: Florida International University Press. ISBN 0-8130-0998-7.

- Harris, David (2004). The Crisis: The President, the Prophet, and the Shah — 1979 and the Coming of Militant Islam. New York & Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-32394-2.

- Hiro, Dilip (1989). Holy Wars: The Rise of Islamic Fundamentalism. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-90208-8. (Chapter 6: Iran: Revolutionary Fundamentalism in Power.)