Quantity theory of money

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In economics, the quantity theory of money is a theory emphasizing the positive relationship of overall prices or the nominal value of expenditures to the quantity of money.

It is the mainstream economic theory of the price level. Alternative theories include the real bills doctrine and the more recent fiscal theory of the price level.

Contents |

[edit] Origins and development of the quantity theory

The quantity theory descends from Copernicus,[1] Jean Bodin,[2] and various others who noted the increase in prices following the import of gold and silver, used in the coinage of money, from the New World. The “equation of exchange” relating the supply of money to the value of money transactions was stated by John Stuart Mill[3] who expanded on the ideas of David Hume.[4] The quantity theory was developed by Simon Newcomb,[5] Alfred de Foville,[6] Irving Fisher[7], and Ludwig von Mises[8] in the latter 19th and early 20th century. It was influentially restated by Milton Friedman in the post-Keynesian era.[9]

Academic discussion remains over the degree to which different figures developed the theory.[10] For instance, Bieda argues that Copernicus's observation

Money can lose its value through excessive abundance, if so much silver is coined as to heighten people's demand for silver bullion. For in this way, the coinage's estimation vanishes when it cannot buy as much silver as the money itself contains […]. The solution is to mint no more coinage until it recovers its par value.[10]

amounts to a statement of the theory,[11] while other economic historians date the discovery later, to figures such as Jean Bodin, David Hume, and John Stuart Mill.[12][10]

Historically, the main rival of the quantity theory was the real bills doctrine, which says that the issue of money does not raise prices, as long as the new money is issued in exchange for assets of sufficient value.[13]

[edit] Equation of exchange

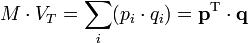

In its modern form, the quantity theory builds upon the following definitional relationship.

where

is the total amount of money in circulation on average in an economy during the period, say a year.

is the total amount of money in circulation on average in an economy during the period, say a year. is the transactions' velocity of money, that is the average frequency across all transactions with which a unit of money is spent. This reflects availability of financial institutions, economic variables, and choices made as to how fast people turn over their money.

is the transactions' velocity of money, that is the average frequency across all transactions with which a unit of money is spent. This reflects availability of financial institutions, economic variables, and choices made as to how fast people turn over their money. and

and  are the price and quantity of the i-th transaction.

are the price and quantity of the i-th transaction. is a vector of the

is a vector of the  .

. is a vector of the

is a vector of the  .

.

Mainstream economics accepts a simplification, the equation of exchange:

where

- PT is the price level associated with transactions for the economy during the period

- T is an index of the real value of aggregate transactions.

The previous equation presents the difficulty that the associated data are not available for all transactions. With the development of national income and product accounts, emphasis shifted to national-income or final-product transactions, rather than gross transactions. Economists may therefore work with the form

where

- V is the velocity of money in final expenditures.

- Q is an index of the real value of final expenditures.

As an example, M might represent currency plus deposits in checking and savings accounts held by the public, Q real output with P the corresponding price level, and  the nominal (money) value of output. In one empirical formulation, velocity was taken to be “the ratio of net national product in current prices to the money stock”.[14]

the nominal (money) value of output. In one empirical formulation, velocity was taken to be “the ratio of net national product in current prices to the money stock”.[14]

Thus far, the theory is not particularly controversial. But there are questions of the extent to which each of these variables is dependent upon the others. Without further restrictions, it does require that change in the money supply would change the value of any or all of P, Q, or  . For example, a 10% increase in M could be accompanied by a 10% decrease in V, leaving PQ unchanged.

. For example, a 10% increase in M could be accompanied by a 10% decrease in V, leaving PQ unchanged.

[edit] A rudimentary theory

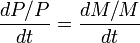

The equation of exchange can be used to form a rudimentary theory of inflation.

If V and Q were constant, then:

and thus

where

- t is time.

That is to say that, if V and Q were constant, then the inflation rate would exactly equal the growth rate of the money supply.

[edit] Quantity theory and evidence

As restated by Milton Friedman, the quantity theory emphasizes the following relationship of the nominal value of expenditures PQ and the price level P to the quantity of money M:

The plus signs indicate that a change in the money supply is hypothesized to change nominal expenditures and the price level in the same direction (for other variables held constant).

Friedman described the empirical regularity of substantial changes in the quantity of money and in the level of prices as perhaps the most-evidenced economic phenomenon on record.[15] Empirical studies have found relations consistent with the models above and with causation running from money to prices. The short-run relation of a change in the money supply in the past has been relatively more associated with a change in real output Q than the price level P in (1) but with much variation in the precision, timing, and size of the relation. For the long-run, there has been stronger support for (1) and (2) and no systematic association of Q and M.[16]

[edit] Principles

The theory above is based on the following hypotheses:

- The source of inflation is fundamentally derived from the growth rate of the money supply.

- The supply of money is exogenous.

- The demand for money, as reflected in its velocity, is a stable function of nominal income, interest rates, and so forth.

- The mechanism for injecting money into the economy is not that important in the long run.

- The real interest rate is determined by non-monetary factors: (productivity of capital, time preference).

[edit] Decline of money-supply targetting

An application of the quantity-theory approach aimed at removing monetary policy as a source of macroeconomic instability was to target a constant, low growth rate of the money supply.[17] Still, practical identification of the relevant money supply, including measurement, was always somewhat controversial and difficult. As financial intermediation grew in complexity and sophistication in the 1980s and 1990s, it became more so. As a result, some central banks, including the U.S. Federal Reserve, which had targeted the money supply, reverted to targeting interest rates. But monetary aggregates remain a leading economic indicator.[18] with "some evidence that the linkages between money and economic activity are robust even at relatively short-run frequencies."[19]

[edit] References

- Friedman, Milton (1987). “quantity theory of money”, The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 4, pp. 3-20.

- Mises, Ludwig Heinrich Edler von; Human Action: A Treatise on Economics (1949), Ch. XVII “Indirect Exchange”, §4. “The Determination of the Purchasing Power of Money”.

- ^ Nicolaus Copernicus (1517), memorandum on monetary policy.

- ^ Jean Bodin, Responses aux paradoxes du sieur de Malestroict (1568).

- ^ John Stuart Mill (1848), Principles of Political Economy.

- ^ David Hume (1748), “Of Interest,” "Of Interest" in Essays Moral and Political.

- ^ Simon Newcomb (1885), Principles of Political Economy.

- ^ Alfred de Foville (1907), La Monnaie.

- ^ Irving Fisher (1911), The Purchasing Power of Money,

- ^ von Mises, Ludwig Heinrich; Theorie des Geldes und der Umlaufsmittel [The Theory of Money and Credit]

- ^ Milton Friedman (1956), “The Quantity Theory of Money: A Restatement” in Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money, edited by M. Friedman. Reprinted in The Optimum Quantity of Money (2005), pp. 51-67.

- ^ a b c Volckart, Oliver (1997), "Early beginnings of the quantity theory of money and their context in Polish and Prussian monetary policies, c. 1520-1550", The Economic History Review 50 (3): 430–449

- ^ Bieda, K. (1973), "Copernicus as an economist", Economic Record 49: 89–103

- ^ Wennerlind, Carl (2005), "David Hume's monetary theory revisited", Journal of Political Economy 113 (1): 233–237

- ^ Roy Green (1987), “real bills dcctrine”, in The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 4, pp. 101-02.

- ^ Milton Friedman, and Anna J. Schwartz, (1965). The Great Contraction 1929–1933. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00350-5.

- ^ Milton Friedman (1987), “quantity theory of money”, The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 4, p. 15.

- ^ Summarized in Friedman (1987), “quantity theory of money”, pp. 15-17.

- ^ Friedman (1987), “Quantity Theory of Money”, p. 19.

- ^ NA (2005), How Does the Fed Determine Interest Rates to Control the Money Supply?”, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. February,[1]

- ^ R.W. Hafer and David C. Wheelock (2001), “The Rise and Fall of a Policy Rule: Monetarism at the St. Louis Fed, 1968-1986”, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Review, January/February, p. 19.

[edit] See also

- Classical dichotomy

- Equation of exchange

- Income velocity of money

- Liquidity preference

- Monetarism

- Monetary Disequilibrium Theory

- Monetary inflation

- Monetary policy

- Money demand

- Money illusion

- Neutrality of money

[edit] Alternative theories

- Benjamin Anderson (critic of mainstream variant)

- Fiscal theory of the price level

- Real bills doctrine

[edit] External links

- The Quantity Theory of Money from John Stuart Mill through Irving Fisher from the New School

- “Quantity theory of money” at Formularium.org — calculate M, V, P and Q with your own values to understand the equation

- How to Cure Inflation (from a Quantity Theory of Money perspective) from Aplia Econ Blog