International Organization for Standardization

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Logo of ISO in English |

|

list of members |

|

| Formation | 23 February 1947 |

|---|---|

| Type | NGO |

| Purpose/focus | International standardization |

| Headquarters | |

| Membership | 158 members |

| Official languages | English and French |

| Website | www.iso.org |

The International Organization for Standardization (Organisation internationale de normalisation), widely known as ISO (pronounced /ˈɑɪsəʊ/), is an international-standard-setting body composed of representatives from various national standards organizations. Founded on 23 February 1947, the organization promulgates worldwide proprietary industrial and commercial standards. It is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland.[1] While ISO defines itself as a non-governmental organization, its ability to set standards that often become law, either through treaties or national standards, makes it more powerful than most non-governmental organizations. In practice, ISO acts as a consortium with strong links to governments.

Contents |

[edit] Name and abbreviation

The organization's logos in its two official languages, English and French, include the word ISO (pronounced /ˈɑɪsəʊ/), and it is usually referred to by this short-form name. ISO is not an acronym or initialism for the organization's full name in either official language. Rather, the organization adopted ISO based on the Greek word isos (ἴσος), meaning equal. Recognizing that the organization’s initials would be different in different languages, the organization's founders chose ISO as the universal short form of its name. This, in itself, reflects the aim of the organization: to equalize and standardize across cultures.[2][3]

[edit] International Standards and other publications

ISO's main products are the International Standards. ISO also publishes Technical Reports, Technical Specifications, Publicly Available Specifications, Technical Corrigenda, and Guides.[4]

International Standards are identified in the format ISO[/IEC][/ASTM] [IS] nnnnn[:yyyy] Title, where nnnnn is the number of the standard, yyyy is the year published, and Title describes the subject. IEC for International Electrotechnical Commission is included if the standard results from the work of ISO/IEC JTC1 (the ISO/IEC Joint Technical Committee). ASTM is used for standards developed in cooperation with ASTM International. The date and IS are not used for an incomplete or unpublished standard, and may under some circumstances be left off the title of a published work.

Technical Reports are issued when "a technical committee or subcommittee has collected data of a different kind from that which is normally published as an International Standard".[4] such as references and explanations. The naming conventions for these are the same as for standards, except TR prepended instead IS in the report's name. Examples:

- ISO/IEC TR 17799:2000 Code of Practice for Information Security Management

- ISO/TR 19033:2000 Technical product documentation — Metadata for construction documentation

Technical Specifications can be produced when "the subject in question is still under development or where for any other reason there is the future but not immediate possibility of an agreement to publish an International Standard". Publicly Available Specifications may be "an intermediate specification, published prior to the development of a full International Standard, or, in IEC may be a 'dual logo' publication published in collaboration with an external organization".[4] Both are named by convention similar to Technical Reports, for example:

- ISO/TS 16952-1:2006 Technical product documentation — Reference designation system — Part 1: General application rules

- ISO/PAS 11154:2006 Road vehicles — Roof load carriers

ISO sometimes issues a Technical Corrigendum. These are amendments to existing standards because of minor technical flaws, usability improvements, or to extend applicability in a limited way. Generally, these are issued with the expectation that the affected standard will be updated or withdrawn at its next scheduled review.[4]

ISO Guides are meta-standards covering "matters related to international standardization".[4] They are named in the format "ISO[/IEC] Guide N:yyyy: Title", for example:

- ISO/IEC Guide 2:2004 Standardization and related activities — General vocabulary

- ISO/IEC Guide 65:1996 General requirements for bodies operating product certification

[edit] ISO document copyright

ISO documents are copyrighted and ISO charges for copies of most. ISO does not, however, charge for most draft copies of documents in electronic format. Although useful, care must be taken using these drafts as there is the possibility of substantial change before it becomes finalized as a standard. Some standards by ISO and its official U.S. representative (and the International Electrotechnical Commission's via the U.S. National Committee) are made freely available.[5][6]

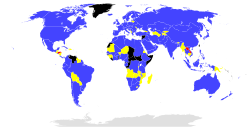

[edit] Members

ISO has 158 national members,[7] out of the 195 total countries in the world.

ISO has three membership categories:

- Member bodies are national bodies that are considered to be the most representative standards body in each country. These are the only members of ISO that have voting rights.

- Correspondent members are countries that do not have their own standards organization. These members are informed about ISO's work, but do not participate in standards promulgation.

- Subscriber members are countries with small economies. They pay reduced membership fees, but can follow the development of standards.

Participating members are called "P" members as opposed to observing members which are called "O" members.

[edit] Products named after ISO

The fact that many of the ISO-created standards are ubiquitous has led, on occasion, to common use of "ISO" to describe the actual product that conforms to a standard. Some examples of this are:

- CD images end in the file extension "ISO" to signify that they are using the ISO 9660 standard filesystem as opposed to another file system - hence CD images are commonly referred to as "ISOs". Virtually all computers with CD-ROM drives can read CDs that use this standard. Some DVD-ROMs also use ISO 9660 filesystems.

- Photographic film's sensitivity to light, its "film speed," is described by ISO 5800:1987. Hence, the film's speed is often referred to as its "ISO number."

[edit] ISO/IEC Joint Technical Committee 1

To deal with the consequences of substantial overlap in areas of standardization and work related to information technology, ISO and IEC formed a Joint Technical Committee known as the ISO/IEC JTC1. It was the first such joint committee, and to date remains the only one.

[edit] IWA document

Like ISO/TS, International Workshop Agreement (IWA) is another armoury of ISO for providing rapid response to requirements for standardization in areas where the technical structures and expertise are not currently in place. The utility harmonizes technical urgency industrial wide.

[edit] Criticism

With the exception of a small number of isolated standards,[8] ISO standards are normally not available free of charge, but for a purchase fee,[9] which has been seen by some as too expensive for small Open source projects.[10]

The ISO/IEC JTC1 fast-track procedures ("Fast-track" as used by OOXML and "PAS" as used by OpenDocument) have garnered criticism in relation to the standardization of Office Open XML (ISO/IEC 29500). Martin Bryan, outgoing Convenor of ISO/IEC JTC1/SC34 WG1, is quoted by saying:

I would recommend my successor that it is perhaps time to pass WG1’s outstanding standards over to OASIS, where they can get approval in less than a year and then do a PAS submission to ISO, which will get a lot more attention and be approved much faster than standards currently can be within WG1.

The disparity of rules for PAS, Fast-Track and ISO committee generated standards is fast making ISO a laughing stock in IT circles. The days of open standards development are fast disappearing. Instead we are getting 'standardization by corporation'.[11]

Computer security entrepreneur and Ubuntu investor, Mark Shuttleworth, commented on the Standardization of Office Open XML process by saying

I think it de-values the confidence people have in the standards setting process,

and Shuttleworth alleged that ISO did not carry out its responsibility. He also noted that Microsoft had intensely lobbied many countries that traditionally had not participated in ISO and stacked technical committees with Microsoft employees, solution providers and resellers sympathetic to Office Open XML.

When you have a process built on trust and when that trust is abused, ISO should halt the process ... ISO is an engineering old boys club and these things are boring so you have to have a lot of passion … then suddenly you have an investment of a lot of money and lobbying and you get artificial results ... The process is not set up to deal with intensive corporate lobbying and so you end up with something being a standard that’s not clear.[12]

[edit] See also

- American National Standards Institute (ANSI)

- Deutsches Institut für Normung, German Institute for Standardization (DIN)

- British Standards

- Countries in International Organization for Standardization

- Canadian Standards Association

- European Committee for Standardization (CEN)

- Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) set of standards (GOST)

- International Classification for Standards

- International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) and ISO/IEC standards.

- International healthcare accreditation

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU)

- ISO A4

- ISO country code

- List of ISO standards

- Standardization

- Standards organization

- Terminology planning policy

- CARICOM Regional Organisation for Standards and Quality (CROSQ)

[edit] References

- ^ "Discover ISO – Meet ISO". ISO. © 2007. http://www.iso.org/iso/about/discover-iso_meet-iso.htm. Retrieved on 2007-09-07.

- ^ "ISO's name". ISO. 2007. http://www.iso.org/iso/en/networking/pr/isoname/isoname.html. Retrieved on 2007-09-07.

- ^ "Discover ISO – ISO's name". ISO. 2007. http://www.iso.org/iso/about/discover-iso_meet-iso/discover-iso_isos-name.htm. Retrieved on 2007-09-07.

- ^ a b c d e The ISO directives are published in two distinct parts:

* "ISO Directives, Part 1: Procedures for the Technical Work. 5th Edition" (pdf). ISO/IEC. 2004. http://www.iec.ch/tiss/iec/Directives-Part1-Ed5.pdf. Retrieved on 2007-09-07.

* "ISO Directives, Part 2: Rules for the structure and drafting of International Standards. 5th Edition" (pdf). ISO/IEC. 2004. http://www.iec.ch/tiss/iec/Directives-Part2-Ed5.pdf. Retrieved on 2007-09-07. - ^ "Freely Available ISO Standards". ISO. Last updated 2007-08-08. http://isotc.iso.org/livelink/livelink/fetch/2000/2489/Ittf_Home/PubliclyAvailableStandards.htm. Retrieved on 2007-09-07.

- ^ "Free ANSI Standards". http://webstore.ansi.org/ansidocstore/free_standards.asp. Retrieved on 2007-06-19.

- ^ "General information on ISO". ISO. © 2009. http://www.iso.org/iso/support/faqs/faqs_general_information_on_iso.htm. Retrieved on 2009-1-29.

- ^ "Freely Available Standards". ISO. http://standards.iso.org/ittf/PubliclyAvailableStandards/index.html. Retrieved on 2008-04-26.

- ^ "Shopping FAQs". ISO. http://www.iso.org/iso/store/shopping_faqs.htm. Retrieved on 2008-04-26.

- ^ Jelliffe, Rick (2007-08-01). "Where to get ISO Standards on the Internet free". oreillynet.com. http://www.oreillynet.com/xml/blog/2007/08/where_to_get_iso_standards_on.html. Retrieved on 2008-04-26. "The lack of free online availability has effectively made ISO standard irrelevant to the (home/hacker section of the) Open Source community"

- ^ "Report on WG1 activity for December 2007 Meeting of ISO/IEC JTC1/SC34/WG1 in Kyoto". iso/jtc1 sc34. November 29,07. http://www.jtc1sc34.org/repository/0940.htm.

- ^ "Ubuntu’s Shuttleworth blames ISO for OOXML’s win". ZDNet.com. April 01,08. http://blogs.zdnet.com/open-source/?p=2222.

[edit] External links

- ISO's official website (free access to the catalogue of standards only, not to the contents)

- Publicly Available Standards (free access to a small subset of the standards)

- ISO/IEC JTC1

- ISO Advanced search for standards and/or projects