Classical order

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

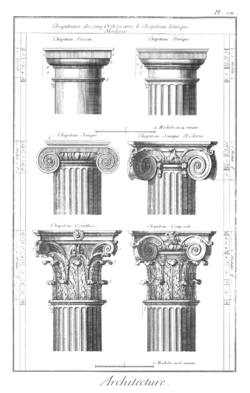

A classical order is one of the ancient styles of building design in the classical tradition, distinguished by their proportions and their characteristic profiles and details, but most quickly recognizable by the type of column and capital employed. Each style also has its proper entablature, consisting of architrave, frieze and cornice. From the sixteenth century onwards, theorists recognized five orders.

Ranged in the engraving (illustration, right), from the stockiest and most primitive to the richest and most slender, they are: Tuscan (Roman) and Doric (Greek and Roman, illustrated here in its Roman version); Ionic (Greek version) and Ionic (Roman version); Corinthian (Greek and Roman) and composite (Roman). The ancient and original orders of architecture are no more than three, the Doric, Ionic and Corinthian, which were invented by the Greeks. To these the Romans added two, the Tuscan, which they made simpler than the Doric, and the Composite, which was more ornamental than the Corinthian.

The order of a classical building is like the mode or key of classical music. It is established by certain modules like the intervals of music, and it raises certain expectations in an audience attuned to its language. The orders are like the grammar or rhetoric of a written composition.

Contents |

[edit] Parts of a column

A column is divided into a shaft, its base and its capital. In classical buildings the horizontal structure that is supported on the columns like a beam is called an entablature. The entablature is commonly divided into the architrave, the frieze and the cornice. To distinguish between the different Classical orders, the capital is used, having the most distinct characteristics.

A complete column and entablature consist of a number of distinct parts. The stylobate is the flat pavement on which the columns are placed. Standing upon the stylobate is the plinth, a square block – sometimes circular – which forms the lowest part of the base. The remainder of the base may be given one or many moldings with profiles. Common examples are the convex torus and the concave scotia, separated by fillets or bands.

On top of the base, the shaft is placed vertically. The shaft is cylindrical in shape and both long and narrow. The shaft is sometimes articulated with vertical hollow grooves or fluting. The shaft is wider at the bottom than at the top, because its entasis, beginning a third of the way up, imperceptibly makes the column slightly more slender at the top.

The capital rests on the shaft. It has a load-bearing function, which concentrates the weight of the entablature on the supportive column, but it primarily serves an aesthetic purpose. The simplest form of the capital is the Doric, consisting of three parts. The necking is the continuation of the shaft, but is visually separated by one or many grooves. The echinus lies atop the necking. It is a circular block that bulges outwards towards the top in order to support the abacus, which is a square or shaped block that in turn supports the entablature.

The entablature consists of three horizontal layers, all of which are visually separated from each other using moldings or bands. The three layers of the entablature have distinct names: the architrave comes at the bottom, the frieze is in the middle and the molded cornice lies on the top. In Roman and post-Renaissance work, the entablature may be carried from column to column in the form of an arch that springs from the column that bears its weight, retaining its divisions and sculptural enrichment, if any.

[edit] Measurement

The height of a column is measured in terms of a ratio between the diameter of the shaft at its base compared to the height of the column. A Doric column can be described as seven diameters high, an Ionic column as eight diameters high and a Corinthian column nine diameters high. Sometimes this is given as seven lower diameters high, in order to make sure which part of the shaft has been measured.

[edit] Greek orders

There are three distinct orders in Ancient Greek architecture: Doric, Ionic, and, later, Corinthian. These three were adopted by the Romans, who modified their capitals. The Roman adoption of the Greek orders took place in the first century BC. The three Ancient Greek orders have since been consistently used in neo-classical Western architecture.

Sometimes the Doric order is considered the earliest order, but there is no evidence to support this. Rather, the Doric and Ionic orders seem to have appeared at around the same time, the Ionic in eastern Greece and the Doric in the west and mainland.

Both the Doric and the Ionic order appear to have originated in wood. The Temple of Hera in Olympia is the oldest well-preserved temple of Doric architecture. It was built just after 600 BC. The Doric order later spread across Greece and into Sicily where it was the chief order for monumental architecture for 800 years.

[edit] Doric order

The Doric order originated on the mainland and western Greece. It is the simplest of the orders, characterized by short, faceted, heavy columns with plain, round capitals (tops) and no base. With only four to eight diameters in height, the columns are the most squat of all orders. The shaft of the Doric order is channeled with 20 flutes. The capital consists of a necking which is of a simple form. The echinus is convex and the abacus is square.

Above the capital is a square abacus connecting the capital to the entablature. The Entablature is divided into two horizontal registers, the lower part of which is either smooth or divided by horizontal lines. The upper half is distinctive for the Doric order. The frieze of the Doric entablature is divided into triglyphs and metopes. A triglyph is a unit consisting of three vertical bands which are separated by grooves. Metopes are plain or carved reliefs.

The Greek forms of the Doric order come without an individual base. They instead are placed directly on the stylobate. Later forms, however, came with the conventional base consisting of a plinth and a torus. The Roman versions of the Doric order have smaller proportions. As a result they appear lighter than the Greek orders.

[edit] Ionic order

The Ionic order came from eastern Greece, where its origins are entwined with the similar but little known Aeolic order. It is distinguished by slender, fluted pillars with a large base and two opposed volutes (also called scrolls) in the echinus of the capital. The echinus itself is decorated with an egg-and-dart motif. The Ionic shaft comes with four more flutes than the Doric counterpart (totalling 24). The Ionic base has two convex moldings called tori which are separated by a scotia.

The Ionic order is also marked by an entasis, a curved tapering in the column shaft. A column of the ionic order is nine or lower diameters. The shaft itself is eight meters high. The architrave of the entablature commonly consists of three stepped bands (fasciae). The frieze comes without the Doric triglyph and metope. The frieze sometimes comes with a continuous ornament such as carved figures.

[edit] Corinthian order

The Corinthian order is the most ornate of the Greek orders, characterized by a slender fluted column having an ornate capital decorated with two rows of acanthus leaves and four scrolls. It is commonly regarded as the most elegant of the three orders.

The shaft of the Corinthian order has 24 flutes. The column is commonly ten diameters high.

Designed by Callimachus, a Greek sculptor of the 5th century BC. The oldest known building to be built according to the Corinthian order is the monument of Lysicrates in Athens. It was built in 335 to 334 BC. The Corinthian order was raised to rank by the writings of the Roman writer Vitruvius in the 1st century BC.

[edit] Roman orders

The Romans adapted all the Greek orders and also developed two orders of their own, basically modification of Greek orders. The Romans also invented the superimposed order. A superimposed order is when successive stories of a building have different orders. The heaviest orders were at the bottom, whilst the lightest came at the top. This means that the Doric order was the order of the ground floor, the Ionic order was used for the middle storey, while the Corinthian or the Composite order was used for the top storey.

The Colossal order was invented by architects in the Renaissance. The Colossal order is characterized by columns that extend the height of two or more stories.

[edit] Tuscan order

The Tuscan order has a very plain design, with a plain shaft, and a simple capital, base, and frieze. It is a simplified adaptation of the Doric order by the Romans. The Tuscan order is characterized by an unfluted shaft and a capital that only consist of an echinus and an abacus. In proportions it is similar to the Doric order, but overall it is significantly plainer. The column is normally seven diameters high. Compared to the other orders, the Tuscan order looks the most solid.

[edit] Composite order

The Composite order is a mixed order, combining the volutes of the Ionic with the leaves of the Corinthian order. Until the Renaissance it was not ranked as a separate order. Instead it was considered as a late Roman form of the Corinthian order. The column of the Composite order is ten diameters high.

[edit] Nonce orders

Several orders, usually based upon the Composite order and only varying in the design of the capitals, have been invented under the inspiration of specific occasions, but have not been used again. Thus they may be termed "nonce orders" on the analogy of nonce words. Robert Adam's brother James was in Rome in 1762, drawing antiquities under the direction of Clérisseau; he invented a British Order, of which his ink-and-wash rendering with red highlighting, is at the Avery Library, Columbia University. Adam published an engraving of it. In its capital the heraldic lion and unicorn take the place of the Composite's volutes, a Byzantine/Romanesque conception, but expressed in terms of neoclassical realism. In 1789 George Dance invented an Ammonite Order, a variant of Ionic substituting volutes in the form of fossil ammonites for John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery in Pall Mall, London.

In the United States Benjamin Latrobe, the architect of the Capitol building in Washington DC, designed a series of botanically American orders. Most famous is the order substituting corncobs and their husks, which was executed by Giuseppe Franzoni and employed in the small domed Vestibule of the Supreme Court. Only the Supreme Court survived the fire of August 24, 1814, nearly intact. With peace restored, Latrobe designed an American order that substituted for the acanthus tobacco leaves, of which he sent a sketch to Thomas Jefferson in a letter, November 5, 1816. He was encouraged to send a model of it, which remains at Monticello. In the 1830s Alexander Jackson Davis admired it enough to make a drawing of it. In 1809 Latrobe invented a second American order, employing magnolia flowers contrained within the profile of classical mouldings, as his drawing demonstrates. It was intended for "the Upper Columns in the Gallery of the Entrance of the Chamber of the Senate" (United States Capitol exhibit).

These nonce orders all express the "speaking architecture" (architecture parlante) that was taught in the Paris courses, most explicitly by Étienne-Louis Boullée, in which sculptural details of classical architecture could be enlisted to speak symbolically, the better to express the purpose of the structure and enrich its visual meaning with specific appropriateness. This idea was taken up strongly in the training of Beaux-Arts architecture, ca 1875-1915: see architecture parlante.

[edit] Original writings

The handbook De architectura of Vitruvius is the only architectural writing that survived from Antiquity. After it was rediscovered in the 15th century, Vitruvius was instantly hailed as the authority on classical orders and architecture in general.

Architects of the Renaissance and the Baroque period in Italy based their rules on Vitruvius' writings. What was added was rules for superimposing the classical orders and the exact proportions of the orders down to the most minute detail.

[edit] Modern approaches

Later the rules of the Renaissance and the Baroque period were disregarded and the original use of the orders was revived, often hailed as the 'correct' use of the orders. Many architects, however, used the Classical orders at their own discretion.

In America, The American Builder's Companion (ISBN 0-486-22236-5), written in the early 1800s by the architect Asher Benjamin, influenced many builders in the eastern states, particularly those who developed what became known as the Federalist style. The Dover edition is based on the 1827 6th edition of the work, and contains 70 plates with many details of columns, capitals, pilasters, plinths, bases, mouldings, architraves, and so on, with numerous instructions regarding proportion as well.

In 20th century modernist architecture, the orders have often become ornaments and regarded as superfluous. Instead columns of steel and reinforced concrete are used. In late 20th century postmodernist architecture, however, elements of the traditional orders have sometimes been reintroduced.

[edit] See also

[edit] Further reading

- Barletta, Barbara A., The Origins of the Greek Architectural Orders (Cambridge University Press) 2001

- Curl, James Stevens, Classical Architecture: An Introduction to Its Vocabulary and Essentials, with a Select Glossary of Terms 2003. ISBN 0-393-73119-7

- Summerson, Sir John, The Classical Language of Architecture MIT Press, 1966. ISBN 0-262-69012-8 (developed from a set of BBC radio talks).

- Tzonis, Alexander, Classical Architecture: The Poetics of Order 1986 ISBN 0-262-70031-X