Foucault pendulum

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Foucault pendulum (pronounced /fuːˈkoʊ/ "foo-KOH"), or Foucault's pendulum, named after the French physicist Léon Foucault, was conceived as an experiment to demonstrate the rotation of the Earth.

Contents |

[edit] The experiment

The experimental apparatus consists of a tall pendulum free to oscillate in any vertical plane. The direction along which the pendulum swings rotates with time because of Earth's daily rotation. The first public exhibition of a Foucault pendulum took place in February 1851 in the Meridian Room of the Paris Observatory. A few weeks later, Foucault made his most famous pendulum when he suspended a 28-kg bob with a 67-metre wire from the dome of the Panthéon in Paris. The plane of the pendulum's swing rotated clockwise 11° per hour, making a full circle in 32.7 hours.

In 1851 it was well known that Earth rotated: observational evidence included Earth's measured polar flattening and equatorial bulge. However, Foucault's pendulum was the first dynamic proof of the rotation in an easy-to-see experiment, and it created a sensation in the academic world and society at large.

At either the North Pole or South Pole, the plane of oscillation of a pendulum remains fixed with respect to the fixed stars while Earth rotates underneath it, taking one sidereal day to complete a rotation. So relative to Earth, the plane of oscillation of a pendulum at the North or South Pole undergoes a full clockwise or counterclockwise rotation during one day, respectively. When a Foucault pendulum is suspended on the equator, the plane of oscillation remains fixed relative to Earth. At other latitudes, the plane of oscillation precesses relative to Earth, but slower than at the pole; the angular speed, α (measured in clockwise degrees per sidereal day), is proportional to the sine of the latitude, φ:

Here, latitudes north and south of the equator are defined as positive and negative, respectively. For example, a Foucault pendulum at 30° south latitude, viewed from above by an earthbound observer, rotates counterclockwise 180° in one day.

In order to demonstrate the rotation of the Earth without the philosophical complication of the latitudinal dependence, Foucault used a gyroscope in an 1852 experiment. The gyroscope's spinning rotor tracks the stars directly. Its axis of rotation is observed to return to its original orientation with respect to the earth after one day whatever the latitude, not subject to the unbalanced Coriolis forces acting on the pendulum as a result of its geometric asymmetry.

A Foucault pendulum requires care to set up because imprecise construction can cause additional veering which masks the terrestrial effect. The initial launch of the pendulum is critical; the traditional way to do this is to use a flame to burn through a thread which temporarily holds the bob in its starting position, thus avoiding unwanted sideways motion. Air resistance damps the oscillation, so Foucault pendulums in museums often incorporate an electromagnetic or other drive to keep the bob swinging; others are restarted regularly. In the latter case, a launching ceremony may be performed as an added show.

[edit] Foucault pendulum precession as a form of parallel transport

From the perspective of an inertial frame moving in tandem with Earth, but not sharing its rotation, the suspension point of the pendulum traces out a circular path during one sidereal day. At the latitude of Paris a full precession cycle takes 32 hours, so after one sidereal day, when the Earth is back in the same orientation as one sidereal day before, the oscillation plane has turned 90 degrees. If the plane of swing was north-south at the outset, it is east-west one sidereal day later. This implies that there has been exchange of momentum; the Earth and the pendulum bob have exchanged momentum. (The Earth is so much heavier than the pendulum bob that the Earth's change of momentum is totally unnoticable. Nonetheless, since the pendulum bob's plane of swing has shifted the conservation laws imply that there must have been exchange.)

Rather than tracking the change of momentum the precession of the oscillation plane can efficiently be described as a case of parallel transport. For that it is assumed that the precession rate is proportional to the projection of the angular velocity of Earth onto the normal direction to Earth, which implies that the plane of oscillation will undergo parallel transport. The difference between initial and final orientations is  in which case the Gauss-Bonnet theorem applies. α is also called the holonomy or geometric phase of the pendulum. Thus, when analyzing earthbound motions, the Earth frame is not an inertial frame, but rather rotates about the local vertical at an effective rate of

in which case the Gauss-Bonnet theorem applies. α is also called the holonomy or geometric phase of the pendulum. Thus, when analyzing earthbound motions, the Earth frame is not an inertial frame, but rather rotates about the local vertical at an effective rate of  radians per day.

radians per day.

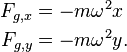

From the perspective of an Earth-bound coordinate system with its x-axis pointing east and its y-axis pointing north, the precession of the pendulum is described by the Coriolis force. Consider a planar pendulum with natural frequency ω in the small angle approximation. There are two forces acting on the pendulum bob: the restoring force provided by gravity and the wire, and the Coriolis force. The Coriolis force at latitude φ is horizontal in the small angle approximation and is given by

where Ω is the rotational frequency of Earth, Fc,x is the component of the Coriolis force in the x-direction and Fc,y is the component of the Coriolis force in the y-direction.

The restoring force, in the small angle approximation, is given by

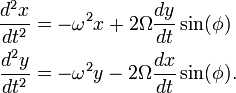

Using Newton's laws of motion this leads to the system of equations

Switching to complex coordinates z = x + iy the equations read

To first order in Ω / ω this equation has the solution

If we measure time in days, then Ω = 2π and we see that the pendulum rotates by an angle of  during one day.

during one day.

[edit] Related physical systems

There are many physical systems that precess in a similar manner to a Foucault pendulum. In 1851, Charles Wheatstone described an apparatus that consists of a vibrating spring that is mounted on top of a disk so that it makes a fixed angle φ with the disk. The spring is struck so that it oscillates in a plane. When the disk is turned, the plane of oscillation changes just like the one of a Foucault pendulum at latitude φ.

Similarly, consider a non-spinning perfectly balanced bicycle wheel mounted on a disk so that its axis of rotation makes an angle φ with the disk. When the disk undergoes a full clockwise revolution, the bicycle wheel will not return to its original position, but will have undergone a net rotation of  .

.

Another system behaving like a Foucault pendulum is a South Pointing Chariot that is run along a circle of fixed latitude on a globe. If the globe is not rotating in an inertial frame, the pointer on top of the chariot will indicate the direction of swing of a Foucault Pendulum that is traversing this latitude.

In physics, these systems are referred to as geometric phases. Mathematically they are understood through parallel transport.

[edit] Foucault pendulums around the world

There are numerous Foucault pendulums around the world, mainly at universities, science museums and planetariums. The experiment has even been carried out at the South Pole.

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- Persson, A. The Coriolis Effect: Four centuries of conflict between common sense and mathematics, Part I: A history to 1885 History of Meteorology 2 (2005)

- Phillips, N. A., What Makes the Foucault Pendulum Move among the Stars? Science and Education, Volume 13, Number 7, November 2004, pp. 653-661(9)

- Classical dynamics of particles and systems, 4ed, Marion Thornton (ISBN 0-03-097302-3 ), P.398-401.

- John B. Hart, Raymond E. Miller and Robert L. Mills A simple geometric model for visualizing the motion of a Foucault pendulum, American Journal of Physics -- January 1987 -- Volume 55, Issue 1, pp. 67-70

- Frank Wilczek and Alfred Shapere, "Geometric Phases in Physics", World Scientific, 1989

- Charles Wheatstone Wikisource: "Note relating to M. Foucault's new mechanical proof of the Rotation of the Earth", pp 65--68

- Julian Rubin, The Invention of the Foucault Pendulum, Following the Path of Discovery, 2007, retrieved 2007-10-31. Directions for repeating Foucault's experiment, on amateur science site.

- L. Mangiarotti, Gennadiĭ Aleksandrovich Sardanashvili (1998). Gauge Mechanics. World Scientific. p. 281. ISBN 9810236034. http://books.google.com/books?id=-N6F44hlnhgC&pg=PA281&dq=%22Berry+connection%22&lr=&as_brr=0.

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Foucault pendulum |

Derivations

- Wolfe, Joe, "A derivation of the precession of the Foucault pendulum".

- "The Foucault Pendulum", derivation of the precession in polar coordinates.

Visualisations, video imaging and models

- "The Foucault Pendulum" By Joe Wolfe, with film clip and animations.

- "Foucault's Pendulum" by Jens-Peer Kuska with Jeff Bryant, Wolfram Demonstrations Project: a computer model of the pendulum allowing manipulation of pendulum frequency, Earth rotation frequency, latitude, and time.

- "Webcam Kirchhoff-Institut für Physik, Universität Heidelberg".

- California academy of sciences, CA Foucault pendulum explanation, in friendly format

- Foucault pendulum model Exposition including a tabletop device that shows the Foucault effect in seconds.

History

- Foucault, M. L., Physical demonstration of the rotation of the Earth by means of the pendulum, Franklin Institute, 2000, retrieved 2007-10-31. Translation of his paper on Foucault pendulum.

- Tobin, William "The Life and Science of Léon Foucault".

Notable

- "South Pole Foucault Pendulum". Winter, 2001.

Educational supplies

- "Science Design's Small Portable Foucault Pendulum" A company selling a Foucault Pendulum for the classroom.