Danse Macabre

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

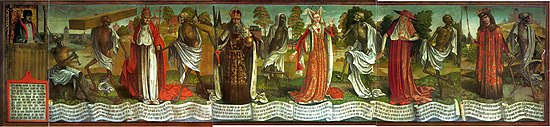

Dance of Death, also variously called Danse Macabre (French), Danza Macabra (Italian and Spanish), or Totentanz (German), is a late-medieval allegory on the universality of death: no matter one's station in life, the dance of death unites all. La Danse Macabre consists of the personified death leading a row of dancing figures from all walks of life to the grave, typically with an emperor, king, youngster, and beautiful girl—all skeletal. They were produced to remind people of how fragile their lives and how vain the glories of earthly life were.[1] Its origins are postulated from illustrated sermon texts; the earliest artistic examples are in a cemetery in Paris from 1424.

Contents |

[edit] Paintings

The earliest artistic example is from the frescoed cemetery of the Church of the Holy Innocents in Paris (1424). There are also works by Konrad Witz, in Basel (1440); Bernt Notke, in Lübeck (1463); and woodcuts designed by Hans Holbein the Younger and executed by Hans Lützelburger (1538).

The deathly horrors of the 14th century—such as recurring famines; the Hundred Years' War in France; and, most of all, the Black Death—were culturally digested throughout Europe. The omnipresent possibility of sudden and painful death increased the religious desire for penitence, but it also evoked a hysterical desire for amusement while still possible; a last dance as cold comfort. The danse macabre combines both desires: similar to the popular mediaeval mystery plays, the dance-with-death allegory was originally a didactic play to remind people of the inevitability of death and to advise them strongly to be prepared all times for death (see memento mori and Ars moriendi).

The earliest examples of such plays, which consisted of short dialogues between Death and each of its victims, can be found in the direct aftermath of the Black Death in Germany (where it was known as the Totentanz, and in Spain as la Danza de la Muerte). The French term danse macabre most likely derives from Latin Chorea Machabæorum, literally "dance of the Maccabees." 2 Maccabees, a deuterocanonical book of the Bible in which the grim martyrdom of a mother and her seven sons is described, was a well-known mediaeval subject. It is possible that the Maccabean Martyrs were commemorated in some early French plays or that people just associated the book’s vivid descriptions of the martyrdom with the interaction between Death and its prey. Both the play and the evolving paintings were ostensive penitential sermons that even illiterate people (who were the overwhelming majority) could understand.

Furthermore, church frescoes dealing with death had a long tradition and were widespread; e.g., the legend of the three men and the three dead: on a ride, three young gentlemen meet the skeletal remains of three of their ancestors who warn them, Quod fuimus, estis; quod sumus, vos eritis (What we were, you are; what we are, you will be). Numerous if often simple fresco versions of that legend from the 13th century onwards have survived (for instance, in the hospital church of Wismar). Since they showed pictorial sequences of men and skeletons covered with shrouds, those paintings can be regarded as cultural precursors of the new genre.

A danse macabre painting normally shows a round dance headed by Death. From the highest ranks of the mediaeval hierarchy (usually pope and emperor) descending to its lowest (beggar, peasant, and child), each mortal’s hand is taken by a skeleton or an extremely decayed body. The famous Totentanz in Lübeck’s Marienkirche (destroyed by an Allied bomb raid in WW II) presented Death as very lively and agile, making the impression that the skeletons were actually dancing, whereas their dancing partners looked clumsy and passive. The apparent class distinction in almost all of these paintings is completely neutralized by Death as the ultimate equalizer, so that a sociocritical element is subtly inherent to the whole genre. The Totentanz of Metzin, for example, shows how a pope crowned with his tiara is being led into hell by the dancing Death.

Generally, a short dialogue is attached to each victim, in which Death is summoning him or her to dance and the summoned is moaning about the near-death. In the first printed Totentanz textbook (Anon.: Vierzeiliger oberdeutscher Totentanz, Heidelberger Blockbuch, approx. 1460), Death addresses, for example, the emperor:

- Her keyser euch hilft nicht das swert

- Czeptir vnd crone sint hy nicht wert

- Ich habe euch bey der hand genomen

- Ir must an meynen reyen komen

- Emperor, your sword won’t help you out

- Sceptre and crown are worthless here

- I’ve taken you by the hand

- For you must come to my dance

At the bottom end of the Totentanz, Death calls, for example, the peasant to dance, and he answers:

- Ich habe gehabt [vil arbeit gross]

- Der sweis mir du[rch die haut floss]

- Noch wolde ich ger[n dem tod empfliehen]

- Zo habe ich des glu[cks nit hie]

- I had to work very much and very hard

- The sweat was running down my skin

- I’d like to escape death nonetheless

- But here I won’t have any luck

[edit] Printing

The earliest known depiction of a print shop appears in a printed image of the Dance of Death, in 1499, in Lyon, by Mattias Huss. It depicts a compositor at his station, which is raised to facilitate his work, and a person running the press. To the right of the print shop, an early book store is shown. Early print shops were gathering places for the literati.

[edit] Musical settings

Musical examples include

- Danse Macabre by Camille Saint-Saëns, 1874

- Mattasin oder Toden Tanz, 1598, by August Nörmiger

- Totentanz by Franz Liszt, 1849, a set of variations based on the plainchant melody "Dies Irae."

- Песни и пляски смерти (Songs and Dances of Death), 1875–77, by Modest Mussorgsky

- Symphony No. 4, 2nd Movement, 1901, by Gustav Mahler

- Totentanz, Oratorium, 1905, by Felix Woyrsch

- Totentanz der Prinzipien, 1914, by Arnold Schoenberg

- Ein Totentanz (Dance of Death), Op. 37, for piano and orchestra, 1931, by Wilhelm Kempff

- The Green Table (Der grüne Tisch), 1932, ballet by Kurt Jooss

- Scherzo (Dance of Death), Op.14, in "Ballad of Heroes," 1939, by Benjamin Britten

- Trio in E minor, Op. 67, 4th movement, "Dance of Death," 1944, by Dmitri Shostakovich

- Totentanz, Der Kaiser von Atlantis, 1944, by Viktor Ullmann

- Zombie Jamboree, 1958, by the Kingston Trio, which they state is based upon a theme by Goethe involving the dance of the dead. The song had been originally performed by a number of Calypso artists.

- Dance of Death, 1964, by John Fahey, a finger-style guitar solo in G minor tuning. An excerpt was used in the film Zabriskie Point.

- Dance with Death, 1968, by Andrew Hill

- Black Angels, 1971, by George Crumb. Contains a danse macabre at the end of part one, "Departure."

- Dancing with Mr. D, 1973, by the Rolling Stones

- Ballo in Fa diesis minore (F♯m), 1977, by Angelo Branduardi

- Danse Macabre, 1984, by Celtic Frost

- Totentanz, 1987, by Coroner

- Danse Macabre, 1994, by Symphony X

- Totentanz, 1996, by In Extremo

- Danse macabre, 1996, by Jaromir Nohavica

- La Danse Macabre, 1996, by Memento Mori

- The Danse Macabre, 1997, by Hecate Enthroned

- Danzon Macabre, 1999, by Kennan Wylie (marching percussion feature)

- Danse Macabre, 2000, by Decapitated

- Danse Macabre, 2001, by The Faint

- La Grande Danse Macabre, 2001, by Marduk

- Dance Macabre, 2002, by Cradle of Filth

- La Danse Macabre du Vampire, 2002, by Theatres des Vampires, a track of Suicide Vampire

- Der makabere tanze des vampires, 2002, by Theatres des Vampires, a bonus track of Suicide Vampire in German

- Dance of Death, 2003, by Iron Maiden

- Kuolon Tanssi, 2003, by Catamenia

- Danse Macabre (ダンスマカブラ), 2004, by Plastic Tree

- Danse Macabre, 2005, by Wintersleep

- Danse Macabre, 2007, by illScarlett

- Danse Macabre, 2007, by Blood (band)

[edit] See also

- Ars moriendi

- Memento mori

- Vanitas

- Macabre

- Death (Tarot card)

- Skeleton (undead)

- The Skeleton Dance

- Dancing mania

- The Seventh Seal

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Danse Macabre |

[edit] Notes

[edit] References

- James M. Clark. The Dance of Death in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, 1950.

- Israil Bercovici. O sută de ani de teatru evriesc în România ("One hundred years of Yiddish/Jewish theater in Romania"), 2nd Romanian-language edition, revised and augmented by Constantin Măciucă. Editura Integral (an imprint of Editurile Universala), Bucharest (1998). ISBN 973-98272-2-5.

- André Corvisier. Les danses macabres, Presses Universitaires de France, 1998. ISBN 2-13-049495-1.

- Rich illustrated Latin translation of the Danse macabre, late 15th century. treasure 4 National Library of Romania

[edit] External links

- A collection of historical images of the Danse Macabre at Cornell's The Fantastic in Art and Fiction

- Holbein's Totentanz

- A collection of 400 paintings of the Dance of Death with the lyrics of Henri Cazalis and the music of Saint Saens at Uzi Dornai's Web Site.

- Photos from a modern performance of Antonie Svoboda and Mirek Vodrážka in May 2001 in Prague at Hynek Semecký web site.