The Smiths

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| The Smiths | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Background information | |

| Origin | Manchester, England |

| Genre(s) | Alternative rock, Indie pop |

| Years active | 1982–1987 |

| Label(s) | Rough Trade, Warner Bros. |

| Associated acts | Electronic, Modest Mouse, Freebass, The Cribs |

| Members | |

| Morrissey Johnny Marr Andy Rourke Mike Joyce |

|

| Former members | |

| Dale Hibbert Craig Gannon |

|

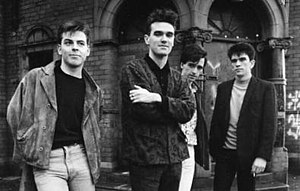

The Smiths were an English rock band formed in Manchester in 1982. Based on the songwriting partnership of Morrissey (vocals) and Johnny Marr (guitar), the band also included Andy Rourke (bass) and Mike Joyce (drums). Critics have called them one of the most important alternative rock bands to emerge from the British independent music scene of the 1980s,[1][2] and the group has had major influence on subsequent artists. Morrissey's lovelorn tales of alienation found an audience amongst youth culture bored by the ubiquitous synthesizer-pop bands of the early 1980s, while Marr's complex melodies helped return guitar-based music to popularity.[3]

The group were signed to the independent record label Rough Trade Records, for whom they released four studio albums and several compilations, as well as numerous non-LP singles. Although they had limited commercial success outside the UK while they were still together, and never released a single that charted higher than number 10 in their home country, The Smiths won a growing following, and remain cult and commercial favourites. The band broke up in 1987 amid disagreements between Morrissey and Marr and have turned down several offers to reform since then.

Contents |

[edit] History

[edit] Formation and early singles

The Smiths were formed in early 1982 by Steven Patrick Morrissey, an unemployed writer who was a big fan of the New York Dolls and briefly fronted punk rock band The Nosebleeds; and John Maher, a guitarist and songwriter. Maher changed his name to Johnny Marr to avoid confusion with the Buzzcocks drummer, and Morrissey performed solely under his surname. Marr had previously been in the band Freak Party along with former Patrol drummer Simon Wolstencroft and bassist Andy Rourke, and Marr and Rourke had previously worked together in The Paris Valentinos along with actor Kevin Kennedy.[4].[5] After recording several demo tapes with Wolstencroft (later of The Fall) on drums, Morrissey and Marr recruited drummer Mike Joyce in the autumn of 1982. Joyce had formerly been a member of punk bands The Hoax and Victim. As well, they added bass player Dale Hibbert, who also provided the group with demo recording facilities at the studio where he worked as a factotum. However, after two gigs, Marr's friend Andy Rourke replaced Hibbert on bass, because neither Hibbert's bass playing nor his personality fit in with the group.

|

|||||

| Problems listening to this file? See media help. | |||||

The band picked their name in part as a reaction against names used by popular synthpop bands of the early 1980s, such as Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark and Spandau Ballet, because they considered these names fancy and pompous. In a 1984 interview Morrissey stated that he chose the name The Smiths "...because it was the most ordinary name" and because he thought that it was "...time that the ordinary folk of the world showed their faces."[6] Signing to indie label Rough Trade Records, they released their first single, "Hand in Glove", in May 1983. The record was championed by DJ John Peel, as were all of their later singles, but failed to chart. The follow-up singles "This Charming Man" and "What Difference Does It Make?" fared better when they reached numbers 25 and 12 respectively on the UK Singles Chart.[7] Aided by praise from the music press and a series of studio sessions for John Peel and David Jensen at BBC Radio 1, The Smiths began to acquire a dedicated fan base.

[edit] The Smiths

In February 1984, the group released their debut album The Smiths, which reached number two on the UK Albums Chart.[7] Both "Reel Around the Fountain" and "The Hand That Rocks the Cradle" met with controversy, supposedly being suggestive of paedophilia. In addition, "Suffer Little Children" caused an uproar after the grandfather of one of the children murdered in the notorious Moors murders heard it on a pub jukebox, and at first thought that the band was trying to commercialise the murders. After meeting with Morrissey, he accepted that the song was a sincere exploration of the impact of the murders. Morrissey subsequently established a friendship with Ann West, the mother of victim Lesley Ann Downey, who is mentioned by name in the song.[8][9]

In 1984, the band released several singles not taken from the album: "Heaven Knows I'm Miserable Now" (the band's first UK top-ten hit) and "William, It Was Really Nothing" (which featured "How Soon Is Now?" as a B-side). The year ended with the compilation album Hatful of Hollow. This collected singles, B-sides and the versions of songs that had been recorded throughout the previous year for the Peel and Jensen shows.

[edit] Meat Is Murder

Early in 1985 the band released their second album, Meat Is Murder. This album was more strident and political than its predecessor, including the pro-vegetarian title track (Morrissey forbade the rest of the group from being photographed eating meat), the light-hearted republicanism of "Nowhere Fast", and the anti-corporal punishment "The Headmaster Ritual" and "Barbarism Begins at Home". The band had also grown more adventurous musically, with Marr adding rockabilly riffs to "Rusholme Ruffians" and Rourke playing a funk bass solo on "Barbarism Begins at Home". The album was preceded by the re-release of the B-side "How Soon is Now?" as a single, and although that song was not on the original LP, it has been added to subsequent releases. Meat Is Murder was the band's only album (barring compilations) to reach number one in the UK charts.[7]

Morrissey brought a political stance to many of his interviews, courting further controversy. Among his targets were the Thatcher government, the monarchy and the famine relief project Band Aid. Morrissey famously quipped of the latter, "One can have great concern for the people of Ethiopia, but it's another thing to inflict daily torture on the people of England."[10] The subsequent single-only release "Shakespeare's Sister" reached number 26 on the UK Singles Chart, although the only single taken from the album, "That Joke Isn't Funny Anymore", was less successful barely making the top 50.[7]

[edit] The Queen Is Dead

|

|||||

| Problems listening to this file? See media help. | |||||

During 1985 the band completed lengthy tours of the UK and the US while recording the next studio record, The Queen Is Dead. The album was released in June 1986, shortly after the single "Bigmouth Strikes Again". The single again featured Marr's strident acoustic guitar rhythms and lead melody guitar lines with wide leaps. The record reached number two in the UK charts,[7] using a mixture of mordant bleakness (e.g. "Never Had No One Ever", which seemed to play up to stereotypes of the band), dry humour (e.g. "Frankly, Mr. Shankly", allegedly a message to Rough Trade boss Geoff Travis disguised as a letter of resignation from a worker to his superior), and synthesis of both, such as in "There Is a Light That Never Goes Out" and "Cemetry Gates".

However, all was not well within the group. A legal dispute with Rough Trade had delayed the album by almost seven months (it had been completed in November 1985), and Marr was beginning to feel the stress of the band's exhausting touring and recording schedule. He later told NME, "'Worse for wear' wasn't the half of it: I was extremely ill. By the time the tour actually finished it was all getting a little bit... dangerous. I was just drinking more than I could handle."[11] Meanwhile, Rourke was fired from the band in early 1986 due to his use of heroin. He received notice of his dismissal via a Post-it note stuck to the windshield of his car. It read, "Andy – you have left The Smiths. Goodbye and good luck, Morrissey."[12] Rourke was temporarily replaced on bass by Craig Gannon (formerly a member of Scottish New Wave band Aztec Camera), but he was reinstated after only a fortnight. Gannon stayed in the band, switching to rhythm guitar. This five-piece recorded the singles "Panic" and "Ask" (with Kirsty MacColl on backing vocals) which reached numbers 11 and 14 respectively on the UK Singles Chart,[7] and toured the UK. After the tour ended in October 1986, Gannon left the band.

The group had become frustrated with Rough Trade and sought a record deal with a major label. Marr told NME in early 1987, ""Every single label came to see us. It was small-talk, bribes, the whole number. I really enjoyed it." The band ultimately signed with EMI, which drew criticism from their fanbase.[11]

[edit] Strangeways, Here We Come and breakup

In early 1987 the single "Shoplifters of the World Unite" was released and reached number 12 on the UK Singles Chart.[7] It was followed by a second compilation, The World Won't Listen – the title was Morrissey's comment on his frustration with the band's lack of mainstream recognition, although the album reached number two in the charts[7] – and the single "Sheila Take a Bow", the band's second (and last during the band's lifetime) UK top-10 hit.[7] Another compilation, Louder Than Bombs, was intended for the overseas market and covered much the same material as The World Won't Listen, with the addition of "Sheila Take a Bow" and material from Hatful of Hollow, as that compilation was yet to be released in the U.S.

Despite their continued success, personal differences within the band – including the increasingly strained relationship between Morrissey and Marr – saw them on the verge of splitting. In July 1987, Marr left the group, and auditions to find a replacement for him proved fruitless. By the time the group's fourth album Strangeways, Here We Come was released in September, the band had split up. The breakdown in the relationship has been primarily attributed to Morrissey becoming annoyed by Marr's work with other artists and Marr growing frustrated by Morrissey's musical inflexibility. Marr particularly hated Morrissey's obsession with covering 1960s pop artists such as Twinkle and Cilla Black. Marr recalled in 1992, "That was the last straw, really. I didn't form a group to perform Cilla Black songs."[13] In a 1989 interview, Morrissey cited the lack of a managerial figure and business problems as reasons for the band's eventual split.[14]

Strangeways, Here We Come peaked at number two in the UK but was only a minor US hit,[7][15] although it was more successful there than the band's previous albums. The album received a lukewarm reception from critics, but both Morrissey and Marr name it as their favourite Smiths album[16]. A couple of further singles from the album were released with earlier live, session and demo tracks as B-sides, and the following year the live album Rank (recorded in 1986 while Gannon was in the band) repeated the UK chart success of previous albums.

[edit] Post-Smiths careers

Shortly after the release of Strangeways, the band were the subject of a documentary in LWT's arts strand The South Bank Show, broadcast on ITV on 18 October 1987.

Following the group's demise, Morrissey began work on a solo recording, collaborating with Strangeways producer Stephen Street and fellow Mancunian Vini Reilly, guitarist for The Durutti Column. The resulting album, Viva Hate (a reference to the end of the Smiths), was released six months later, reaching number one in the UK charts. Morrissey continues to perform and record as a solo artist.

Johnny Marr returned to the music scene in 1989 with New Order's Bernard Sumner and Pet Shop Boy Neil Tennant in the supergroup Electronic. Electronic released three albums over the next decade. Marr was also a member of The The, recording two albums with the group between 1989 and 1993. He has also worked as a session musician and writing collaborator for artists including The Pretenders, Bryan Ferry, Pet Shop Boys, Billy Bragg, Black Grape, Talking Heads, Crowded House and Beck. In 2000 he started another band, Johnny Marr and the Healers, with a moderate degree of success, and later worked as a guest musician on the Oasis album Heathen Chemistry.

In addition to his work as a recording artist, Marr has worked as a record producer on Haven's debut album Between the senses. In 2006 he began work with Modest Mouse's Isaac Brock on songs that eventually featured on the band's 2007 release, We Were Dead Before the Ship Even Sank. The band subsequently announced that Marr was a fully fledged member, and the reformed line-up toured extensively throughout 2006-07. Marr has also been recording with Liam Gallagher of Oasis. In January 2008, Marr had reportedly been adding his skill and experience to a secret songwriting session with Wakefield indie group The Cribs. Sources reveal that they worked together for a week at Moolah Rouge recording studio in Stockport - a favourite haunt of Bolton's Badly Drawn Boy, Damon Gough and fellow northern indie band I Am Kloot - and have penned a number of new songs.[17] Marr has now become a full member of The Cribs.

Andy Rourke and Mike Joyce have continued working together, including doing session work for Morrissey (1988–89) and Sinéad O'Connor, as well as working separately. Rourke has recorded and toured with Proud Mary and is currently forming a group called Freebass with fellow bassists Peter Hook (of New Order and Joy Division) and Mani (of The Stone Roses and Primal Scream). He has recently started a radio career, hosting a show on Saturday evenings on XFM Manchester.

[edit] Court case

In 1996, Joyce took Morrissey and Marr to court, claiming that he had not received his fair share of recording and performance royalties. Morrissey and Marr had claimed the lion's share of The Smiths' recording and performance royalties and allowed ten percent each to Joyce and Rourke. Composition royalties were not an issue, as Rourke and Joyce had never been credited as composers for the band. Morrissey and Marr claimed that the other two members of the band had always agreed to that split of the royalties, but the court found in favour of Joyce and ordered that he be paid over £1 million in back pay and receive twenty-five percent henceforth. As Smiths' royalties had been frozen for two years, Rourke settled for a smaller lump sum to pay off his debts and continued to receive ten percent. While the judge in the case described Morrissey as "devious, truculent and unreliable", he did not state that the singer had been dishonest.[18] Morrissey claimed that he was "...under the scorching spotlight in the dock, being drilled..." with questions such as " 'How dare you be successful?' 'How dare you move on?'". He stated that "The Smiths were a beautiful thing and Johnny [Marr] left it, and Mike [Joyce] has destroyed it."[19] Morrissey appealed against the verdict, but was not successful.[20]

In late November 2005, while appearing on radio station BBC 6 Music, Mike Joyce claimed to be having financial problems and said that he had resorted to selling rare band recordings on eBay. As a teaser, a few minutes of an unfinished instrumental track known as "The Click Track" was premiered on the show. Morrissey hit back at Joyce with a public statement shortly after, on the website true-to-you.net.[21] Relations between Joyce and Rourke cooled significantly as a result of Morrissey's statement which claimed that Joyce had misled the courts. Morrissey claimed that Joyce had not declared that Rourke was entitled to some of the assets seized by Joyce's lawyers from Morrissey.

[edit] 2000s

Both Johnny Marr and Morrissey have repeatedly said in interviews that they will not reunite the band. In 2005, VH1 attempted to get the band back together for a reunion on its Bands Reunited show. The programme abandoned its attempt after host Aamer Haleem was unsuccessful in his attempt to corner Morrissey before a show. In December 2005 it was announced that Johnny Marr and The Healers would play at Manchester v Cancer, a benefit show for cancer research being organised by Andy Rourke and his production company, Great Northern Productions.[22] Rumours suggested that a Smiths reunion would occur at this concert but were dispelled by Johnny Marr on his website.[23] However, Rourke did join Marr onstage for the first time since The Smiths broke up, performing "How Soon Is Now?".

To this day Morrissey refuses to reunite his old band, going as far as to say that he would "rather eat [his] own testicles than re-form The Smiths, and that’s saying something for a vegetarian."[24] In March 2006, Morrissey revealed that The Smiths had been offered $5 million to reunite for a performance at the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival, which he turned down, saying, "No, because money doesn't come into it." He further explained, "It was a fantastic journey. And then it ended. I didn't feel we should have ended. I wanted to continue. [Marr] wanted to end it. And that was that."[25] When asked why he would not reform with The Smiths, Morrissey responded "I feel as if I’ve worked very hard since the demise of The Smiths and the others haven’t, so why hand them attention that they haven’t earned? We are not friends, we don’t see each other. Why on earth would we be on a stage together?"[26]

In August 2007, the NME reported that Morrissey had turned down a near £40 million offer to reunite with Marr for a 50-date world tour in 2008 and 2009. The condition would only be that Morrissey would have to play the dates with Marr, meaning the deal could have gone ahead without Mike Joyce and Andy Rourke.[27] According to an anonymous press release on true-to-you.net, an unofficial fan site tacitly supported by Morrissey, Morrissey was approached in summer 2007 by a "consortium of promoters" with a $75 million offer to tour during the next two years. The offer required Morrissey to make a minimum of fifty worldwide performances with Johnny Marr, under the Smiths' name. true-to-you.net reported that the offer had been refused.[28] Other reports say that the whole $75 million tour was a hoax.[29]

In an October 2007 interview on BBC Radio 5 Live, Johnny Marr hinted at a potential reformation in the future, saying that "stranger things have happened so, you know, who knows?" Marr went on to say that "It's no biggy. Maybe we will in 10 or 15 years' time when we all need to for whatever reasons, but right now Morrissey is doing his thing and I'm doing mine, so that's the answer really." This is the first potential indication of a Smiths reunion from Marr, who previously has stated that reforming the band would be a bad idea.[30]

In October and December 2008, The Sun reported that the Smiths would be reforming to play at the Coachella Festival in 2009.[31] However, Johnny Marr later stated through his management that the rumours were "rubbish".[32]

A Smiths compilation called The Sound of The Smiths was released on 10 November 2008. Johnny Marr supervised the remastering of all the tracks and Morrissey named the record. The album is available as either a one-disc or two-disc version.[33]

In February 2009, following further suggestions of an imminent reunion, Morrissey once again denied the rumours. In an interview with BBC Radio 2, he stated that "People always ask me about reunions and I can't imagine why... the past seems like a distant place, and I'm pleased with that."[34]

[edit] Musical style

Throughout the group's existence, Morrissey and Johnny Marr dictated the musical direction of The Smiths. Marr said in 1990, "[I]t was a 50/50 thing between Morrissey and me. We were completely in sync about which way we should go for each record".[35] Encyclopedia Britannica comments that the band's "non-rhythm-and-blues, whiter-than-white fusion of 1960s rock and postpunk was a repudiation of contemporary dance pop" which was popular in the early 1980s.[36] The band's music purposefully rejected synthesizers and dance music.[13]

Marr's jangly Rickenbacker guitar-playing was influenced by The Byrds, Neil Young's work with Crazy Horse, George Harrison and James Honeyman-Scott of The Pretenders. Marr often tuned his guitar up a full step to F# to accommodate Morrissey's vocal range, and also utilised open tunings. The guitarist devoted his focus to the production of the group's music. Citing producer Phil Spector as an influence, Marr said, "I like the idea of records, even those with plenty of space, that sound 'symphonic'. I like the idea of all the players merging into one atmosphere".[35]

Musically, Morrissey's role in the band was to create vocal melodies and lyrics.[19] Morrissey's lyrics, while superficially depressing, were often full of mordant humour; John Peel remarked that The Smiths were one of the few bands capable of making him laugh out loud. Influenced by his childhood interest in the working-class social realism of 1960s "kitchen sink" television plays, Morrissey wrote about ordinary people and their experiences with despair, rejection and death. While gloomy "...songs such as 'Still Ill' sealed his role as spokesman for disaffected youth", Morrissey's "manic-depressive rants" and his "'woe-is-me' posture inspired some hostile critics to dismiss the Smiths as 'miserabilists.'"[36]

[edit] Imagery

The group had a distinctive visual style on their album and single covers, which often featured colourful images of film and pop stars, usually in duotone, designed by Morrissey and Rough Trade art coordinator Jo Slee. Single covers rarely featured any text other than the band name, and the band themselves did not appear on the outer cover of their UK releases. (Morrissey did, however, appear on an alternative cover for "What Difference Does It Make?", mimicking the pose of the original subject, UK film actor Terence Stamp, after the latter objected to his image being used.) The "cover stars" were an indication of Morrissey's personal interests in obscure or cult film stars, featuring Stamp, Alain Delon, Jean Marais, Warhol protégé Joe Dallesandro, James Dean, figures from 1960s British culture (Viv Nicholson, Pat Phoenix, Yootha Joyce, Shelagh Delaney), or images of unknown models taken from old films or magazines.

The Smiths dressed mainly in ordinary clothes – jeans and plain shirts – which reflected the "back to basics" guitar-and-drums style of the music. This contrasted with the exotic high-fashion image cultivated by New Romantic pop groups such as Spandau Ballet and Duran Duran and highlighted in magazines such as The Face and i-D. Morrissey once wore a fake hearing aid to support a hearing-impaired female fan who was ashamed of using one,[37] and thick-rimmed National Health Service-style glasses.

[edit] Legacy

The Smiths have influenced a number of alternative rock bands through their career. Even as early as 1985, the "band had spawned a rash of soundalike bands, including James, who opened for the group on their spring 1985 tour".[38] The Cranberries combined "the melodic jangle of post-Smiths indie-guitar pop with the lilting, trance-inducing sonic textures of late-'80s dream pop, creating their sound with "trebly, chiming guitars and spare, certain melodies".[39] As well, the band used Stephen Street as producer, who was known for "maximizing the moodiness of the Smiths".[40] The Cranberries fused this sound with lyrics that echoed the lovesick, literary style of Morrissey. "The Smiths singer's bookish, fiercely intelligent lyrics also provided a blueprint for the quiet, literate Scottish band Belle & Sebastian." [41] Marr's guitar playing "was a huge building block for more Manchester legends that followed The Smiths - The Stone Roses"; their guitarist John Squire has stated that Marr was a major influence.[41] Oasis guitarist Noel Gallagher has called The Smiths an influence, especially Marr; Gallagher stated that "when The Jam split, The Smiths started, and I totally went for them."[41]

The "Britpop movement preempted by The Stone Roses and spearheaded by groups like Oasis, Suede and Blur, drew heavily from Morrissey's portrayal of and nostalgia for a bleak urban England of the past."[42] Britpop band Blur formed as a result of seeing The Smiths on The South Bank Show in 1987. However, even though leading bands from the Britpop movement claimed to be influenced by The Smiths, the Britpop bands were at odds with the "basic anti-establishment philosophies of Morrissey and The Smiths", since Britpop "was an entirely commercial construct." In the book Saint Morrissey, the author claims that Britpop "airbrush[ed] Morrissey out of the picture...so that the Nineties and its centrally-planned and coordinated pop economy could happen."[42]

Journalist Chloe Veltman argues that "the fanatical adoration surrounding Morrissey today is founded on nostalgia, specifically a yearning for the Morrissey of the 1980s – the superstar-outsider frontman of The Smiths." She argues that The "Smiths have had a much more profound influence on subsequent culture than Morrissey has had on his own over the entire 17 year history of his solo career." She also points out that the "extensive catalogue of pop bands, plays, novels, films and other cultural artifacts that have been influenced by Morrissey's ideas and aesthetics draw their inspiration from The Smiths rather than Morrissey solo."[42][43]

[edit] Discography

- Studio albums

- The Smiths (1984)

- Meat Is Murder (1985)

- The Queen Is Dead (1986)

- Strangeways, Here We Come (1987)

[edit] Notes

- ^ Reynolds, Simon. Rip It Up and Start Again: Postpunk 1978–1984. Penguin, 2005. p. 392

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Smiths". Allmusic. Retrieved 9 August 2006.

- ^ Sputnikmusic.com

- ^ Wright, Susannah (6 March 2008). "Former Corrie star’s tribute for tragic pal". South Manchester Reporter. http://www.southmanchesterreporter.co.uk/news/s/1039652_former_corrie_stars_tribute_for_tragic_pal. Retrieved on 2008-07-17.

- ^ Robb, John (2001) The Stone Roses and the Resurrection of British Pop, Random House, ISBN 0-09-187887-X, p.30

- ^ "Interview" (http). Melody Maker, cited at Hiddenbyrags.com. 1984. http://www.hiddenbyrags.com/mminterview1984.html. Retrieved on 2007-04-22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Roberts, David (ed.) (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19th edition ed.). HIT Entertainment. pp. 509–510. ISBN 1-904994-10-5.

- ^ Heaven Knows I'm Miserable Now, foreverill.com

- ^ Suffer Little Children lyrics, Passions Just Like Mine website

- ^ "Band Aid vs. Morrissey..." (http). Overyourhead.co.uk. November 18, 2004. http://www.overyourhead.co.uk/2004/11/band-aid-vs.html. Retrieved on 2007-04-22.

- ^ a b Kelly, Danny. "Exile on Mainstream". NME. 14 February 1987.

- ^ Harris, John. "The Smiths - Trouble At Mill/The Queen Is Dead and beyond: part 3". Johnharris.me.uk. http://www.johnharris.me.uk/arch/interview/Smiths/Smiths_pt3.htm. Retrieved on 2007-04-22.

- ^ a b Rogan, Johnny. "The Smiths: Johnny Marr's View". Record Collector. November/December 1992.

- ^ Morrissey-Solo.com

- ^ "Artist Chart History - The Smiths: Albums". Billboard.com. http://www.billboard.com/bbcom/retrieve_chart_history.do?model.chartFormatGroupName=Albums&model.vnuArtistId=5703&model.vnuAlbumId=15763. Retrieved on 2008-08-13.

- ^ Passions Just Like Mine website

- ^ "Marr rocking the Cribs", Manchester Evening News, 26 January 2008

- ^ BBC News (December 11, 1996). "Rock band drummer awarded £1m payout" (http). BBC, cited at Cemetrygates.com. http://www.cemetrygates.com/vault/news/court.html. Retrieved on 2007-04-22.

- ^ a b Nine, Jennifer. "The Importance of Being Morrissey". Melody Maker. 9 August 1997.

- ^ "Joyce vs. Morrissey and Others" (http). England and Wales Court of Appeal (Civil Division) Decisions. 1998. http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/1998/1711.html. Retrieved on 2007-02-16.

- ^ "Statement from Morrissey, 30 November 2005". http://true-to-you.net/morrissey_news_051130_01. Retrieved on 2007-12-07.

- ^ Cohen, Jonathan (2005). "Smiths Members Regrouping For Cancer Benefit" (http). Billboard.com. http://billboard.com/bbcom/news/article_display.jsp?vnu_content_id=1001659262. Retrieved on 2006-08-15.

- ^ "Johnny and the Healers play Manchester Versus Cancer charity concert" (http). Jmarr.com. December 16, 2005. http://www.jmarr.com/. Retrieved on 2007-04-22.

- ^ Antrobus, Stuart (2006). "Morrissey: 'I'd Rather Eat My Testicles Than Re-form The Smiths'" (http). Gigwise.com. http://www.gigwise.com/news.asp?contentid=15239. Retrieved on 2006-08-15.

- ^ Jeckell, Barry A. (2006). "Morrissey: Smiths Turned Down Millions To Reunite" (http). CNN.com. http://www.billboard.com/bbcom/news/article_display.jsp?vnu_content_id=1002198233. Retrieved on 2006-08-15.

- ^ Melia, Daniel (2006). "Morrissey: 'The Smiths Don't Deserve To Be On Stage With Me'" (http). Gigwise.com. http://www.gigwise.com/news.asp?contentid=18006. Retrieved on 2006-08-21.

- ^ Anon (2007). "Morrissey rejects fresh attempt at Smiths reunion" (http). NME.com. http://www.nme.com/news/the-smiths/30599. Retrieved on 2007-08-23.

- ^ "Press release regarding tour dates, 22 August 2007". http://true-to-you.net/morrissey_news_070822_01. Retrieved on 2007-12-07.

- ^ Morrissey announces new album - reunion tour Smiths a hoax, http://www.side-line.com/news_comments.php?id=26177_0_2_0_C, retrieved on 2007-10-

- ^ Johnny Marr Doesn’t Rule Out Smiths Reunion With Morrissey, http://britmusicscene.com/johnny-marr-doesnt-rule-out-smiths-reunion-with-morrissey/, retrieved on 2008-01-08

- ^ "The Smiths to reform for Coachella 2009?", NME, 24 October 2008

- ^ "The Smiths definitely not reuniting for Coachella 2009", NME, 24 October 2008

- ^ New Smiths compilation 'The Sound Of The Smiths' remastered By Johnny Marr

- ^ "Morrissey turns down The Smiths... again". idiomag. 2009-02-13. http://www.idiomag.com/peek/64678/morrissey. Retrieved on 2009-02-13.

- ^ a b Gore, Joe. "Guitar Anti-hero". Guitar Player, January 1990.

- ^ a b Britannica Online: "the Smiths"

- ^ Morrissey & Marr: The Severed Alliance by Johnny Rogan

- ^ allmusic ((( The Smiths > Biography )))

- ^ Review by Stephen Thomas Erlewine from Allmusic

- ^ Rolling Stone: "The Cranberries: Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can't We?"

- ^ a b c BBC news: "The Smiths: The influential alliance"

- ^ a b c The Believer: "The passion of the Morrissey"

- ^ Among these works are "Playwright Shaun Duggan's stage drama William, Douglas Coupland's 1998 novel Girlfriend in a Coma, Andrew Collins' autobiography Heaven Knows I'm Miserable Now, Marc Spitz's novel How Soon is Never? , the pop band Shakespeare's Sister and the Polish filmmaker Przemyslaw Wojcieszek's short fictional film about two Polish fans of The Smiths, Louder Than Bombs, are all named after songs by The Smiths.

[edit] References

- David Bret. Morrissey: Scandal and Passion (Robson 2004; ISBN 1-86105-787-3; covers both Smiths and Morrissey's solo career)

- Simon Goddard. The Smiths: Songs That Saved Your Life (Reynolds and Hearn 2002, 2004²; ISBN 1-903111-47-1, ISBN 1-905287-14-3)

- Mick Middles. The Smiths: The Complete Story (Omnibus 1985, 1988²)

- Johnny Rogan. Morrissey and Marr: The Severed Alliance (Omnibus 1992, 1993²; ISBN 0-7119-3000-7)

- Mark Simpson. Saint Morrissey (SAF, 2003, 2006, 978-0946719754)

[edit] External links

- The Smiths File Online - chronologically relive the history of the Smiths through articles, release reviews, news items and live reviews

- Morrissey-solo - up to date Morrissey and Smiths news

- Passions Just Like Mine - a fansite with a very complete discography

- Vulgar Picture - Illustrated discography of the Smiths and Morrissey

- Radio Broadcast stream from Dutch first & only gig 1984, April 21, Amsterdam @ the Meervaart

|

||||||||||||||||||||