Cryptographic hash function

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A cryptographic hash function is a deterministic procedure that takes an arbitrary block of data and returns a fixed-size bit string, the (cryptographic) hash value, such that an accidental or intentional change to the data will change the hash value. The data to be encoded is often called the "message", and the hash value is sometimes called the message digest or simply digest.

The ideal cryptographic hash function has four main properties:

- it is easy to compute the hash value for any given message,

- it is infeasible to find a message that has a given hash,

- it is infeasible to modify a message without changing its hash,

- it is infeasible to find two different messages with the same hash.

Cryptographic hash functions have many information security applications, notably in digital signatures, message authentication codes (MACs), and other forms of authentication. They can also be used as ordinary hash functions, to index data in hash tables; as fingerprints, to detect duplicate data or uniquely identify files; or as checksums to detect accidental data corruption. Indeed, in information security contexts, cryptographic hash values are sometimes called (digital) fingerprints, checksums, or just hash values, even though all these terms stand for functions with rather different properties and purposes.

Contents |

[edit] Properties

Most cryptographic hash functions are designed to take a string of any length as input and produce a fixed-length hash value.

A cryptographic hash function must be able to withstand all known types of cryptanalytic attack. As a minimum, it must have the following properties:

- Preimage resistance: given h it should be hard to find any m such that h = hash(m). This concept is related to that of one way function. Functions that lack this property are vulnerable to preimage attacks.

- Second preimage resistance: given an input m1, it should be hard to find another input, m2 (not equal to m1) such that hash(m1) = hash(m2). This property is sometimes referred to as weak collision resistance. Functions that lack this property are vulnerable to second preimage attacks.

- Collision resistance: it should be hard to find two different messages m1 and m2 such that hash(m1) = hash(m2). Such a pair is called a (cryptographic) hash collision, and this property is sometimes referred to as strong collision resistance. It requires a hash value at least twice as long as what is required for preimage-resistance, otherwise collisions may be found by a birthday attack.

These properties imply that not even a malicious adversary can replace or modify the input data without changing its digest. Thus, if two strings have the same digest, one can be very confident that they are identical.

A function meeting these criteria may still have undesirable properties. Currently popular cryptographic hash functions are vulnerable to length-extension attacks: given h(m) and len(m) but not m, by choosing a suitable m' an attacker can calculate h (m || m'), where || denotes concatenation. This property can be used to break naive authentication schemes based on hash functions. The HMAC construction works around these problems.

Ideally, one may wish for even stronger conditions. It should be impossible for an adversary to find two messages with substantially similar digests; or to infer any useful information about the data, given only its digest. Therefore, a cryptographic hash function should behave as much as possible like a random function while still being deterministic and efficiently computable.

Checksum algorithms, such as CRC32 and other cyclic redundancy checks, are designed to meet much weaker requirements, and are generally unsuitable as cryptographic hash functions. For example, a CRC was used for message integrity in the WEP encryption standard, but an attack was readily discovered which exploited the linearity of the checksum.

[edit] Meaning of "hard"

In cryptographic practice, "hard" generally means "almost certainly beyond the reach of any adversary who must be prevented from breaking the system". The meaning of the term is therefore somewhat dependent on the application, since the effort that a malicious agent may put into the task is usually proportional to his expected gain. However, since the needed effort usually grows very quickly with the digest length, even a thousand-fold advantage in processing power can be neutralized by adding a few dozen bits to the the latter.

In some theoretical analyses "hard" has a specific mathematical meaning, such as not solvable in asymptotic polynomial worst-case time by a deterministic algorithm. However, those theoretical senses of "hard" have little or no connection to the practical sense above[citation needed].

[edit] Applications

A typical use of a cryptographic hash would be as follows: Alice poses a tough math problem to Bob, and claims she has solved it. Bob would like to try it himself, but would yet like to be sure that Alice is not bluffing. Therefore, Alice writes down her solution, appends a random nonce, computes its hash and tells Bob the hash value (whilst keeping the solution and nonce secret). This way, when Bob comes up with the solution himself a few days later, Alice can prove that she had the solution earlier by revealing the nonce to Bob. (This is an example of a simple commitment scheme; in actual practice, Alice and Bob will often be computer programs, and the secret would be something less easily spoofed than a claimed puzzle solution).

Another important application of secure hashes is verification of message integrity. Determining whether any changes have been made to a message (or a file), for example, can be accomplished by comparing message digests calculated before, and after, transmission (or any other event).

A message digest can also serve as a means of reliably identifying a file; several source code management systems, including Git, Mercurial and Monotone, use the sha1sum of various types of content (file content, directory trees, ancestry information, etc) to uniquely identify them.

A related application is password verification. Passwords are usually not stored in cleartext, for obvious reasons, but instead in digest form. To authenticate a user, the password presented by the user is hashed and compared with the stored hash. This is sometimes referred to as one-way encryption.

For both security and performance reasons, most digital signature algorithms specify that only the digest of the message be "signed", not the entire message. Hash functions can also be used in the generation of pseudorandom bits.

Hashes are used to identify files on peer-to-peer filesharing networks. For example, in an ed2k link, an MD4-variant hash is combined with the file size, providing sufficient information for locating file sources, downloading the file and verifying its contents. Magnet links are another example. Such file hashes are often the top hash of a hash list or a hash tree which allows for additional benefits.

[edit] Hash functions based on block ciphers

There are several methods to use a block cipher to build a cryptographic hash function, specifically a one-way compression function.

The methods resemble the block cipher modes of operation usually used for encryption. All well-known hash functions, including MD4, MD5, SHA-1 and SHA-2 are built from block-cipher-like components designed for the purpose, with feedback to ensure that the resulting function is not bijective.

A standard block cipher such as AES can be used in place of these custom block ciphers; this generally carries a cost in performance, but can be advantageous where a system needs to perform hashing and another cryptographic function such as encryption that might use a block cipher, but is constrained in the code size or hardware area it must fit into, such as in some embedded systems like smart cards.

[edit] Merkle-Damgård construction

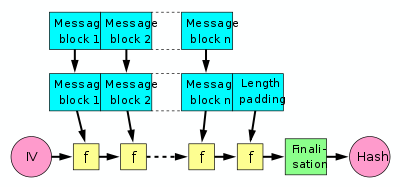

A hash function must be able to process an arbitrary-length message into a fixed-length output. This can be achieved by breaking the input up into a series of equal-sized blocks, and operating on them in sequence using a one-way compression function. The compression function can either be specially designed for hashing or be built from a block cipher. A hash function built with the Merkle-Damgård construction is as resistant to collisions as is its compression function; any collision for the full hash function can be traced back to a collision in the compression function.

The last block processed should also be unambiguously length padded; this is crucial to the security of this construction. This construction is called the Merkle-Damgård construction. Most widely used hash functions, including SHA-1 and MD5, take this form.

The construction has certain inherent flaws, including length-extension and generate-and-paste attacks, and cannot be parallelized. As a result, many entrants in the current NIST hash function competition are built on different, sometimes novel, constructions.

[edit] Use in building other cryptographic primitives

Hash functions can be used to build other cryptographic primitives. For these other primitives to be cryptographically secure, care must be taken to build them correctly.

Message authentication codes (MACs) are often built from hash functions. HMAC is such a MAC.

Just as block ciphers can be used to build hash functions, hash functions can be used to build block ciphers. Luby-Rackoff constructions using hash functions can be provably secure if the underlying hash function is secure. Also, many hash functions (including the SHA hash functions) are built by using a special-purpose block cipher in a Davies-Meyer or other construction; that cipher can also be used in a conventional mode of operation, without the same security guarantees. See SHACAL, BEAR and LION.

Pseudorandom number generators (PRNGs) can be built using hash functions. This is done by combining a (secret) random seed with a counter and hashing it.

Stream ciphers can be built using hash functions. Often this is done by first building a cryptographically secure pseudorandom number generator and then using its stream of random bytes as keystream. SEAL is a stream cipher that uses SHA-1 to generate internal tables, which are then used in a keystream generator more or less unrelated to the hash algorithm; SEAL is not guaranteed to be as strong (or weak) as SHA-1.

[edit] Concatenation of cryptographic hash functions

Concatening outputs from multiple hash functions provides collision resistance at least as good as the strongest of the algorithms included in the concatenated result.[1] For example, SSL uses concatenated MD5 and SHA-1 sums to ensure the protocol will remain secure even if one function is broken.

However, for Merkle-Damgård hash functions, the concatenated function is only as strong as the best component, not stronger.[2] Joux[3] noted that 2-collisions lead to n-collisions: if it's feasible to find two messages with the same MD5 hash, it's effectively no more difficult to find as many messages as the attacker desires with identical MD5 hashes. Among the n messages with the same MD5 hash, there's likely to be a collision in SHA-1. The additional work needed to find the SHA-1 collision (beyond the exponential birthday search) is polynomial. This argument is summarized by Finney.

[edit] Cryptographic hash algorithms

There is a long list of cryptographic hash functions, although many have been found to be vulnerable and should not be used. Even if a hash function has never been broken, a successful attack against a weakened variant thereof may undermine the experts' confidence and lead to its abandonment. For instance, in August 2004 weaknesses were found in a number of hash functions that were popular at the time, including SHA-0, RIPEMD, and MD5. This has called into question the long-term security of later algorithms which are derived from these hash functions — in particular, SHA-1 (a strengthened version of SHA-0), RIPEMD-128, and RIPEMD-160 (both strengthened versions of RIPEMD). Neither SHA-0 nor RIPEMD are widely used since they were replaced by their strengthened versions.

As of 2009, the two most commonly used cryptographic hash functions are MD5 and SHA-1. However, MD5 has been broken; an attack against it was used to break SSL in 2008.[4]

SHA-0 and SHA-1 are members of the SHA family of hash functions developed by the NSA. In February 2005, a successful attack on SHA-1 was reported, finding collisions in about 269 hashing operations, rather than the 280 expected for a 160-bit hash function. In August 2005, another successful attack on SHA-1 was reported, finding collisions in 263 operations. Theoretical weaknesses of SHA-1 exist as well,[5][6] suggesting that it may be practical to break within years. New applications can avoid these problems by using more advanced members of the SHA family, such as SHA-2, or using techniques such as randomized hashing techniques[7][8] that do not require collision resistance.

However, successful attacks[citation needed] on weakened versions of SHA-2 have led NIST to start a competition to design its replacement, which will be given the name SHA-3 and become a FIPS standard.[9]

Some of the following algorithms are known to be insecure; consult the article for each specific algorithm for more information on the status of each algorithm. Note that this list doesn't include candidates in the current NIST hash function competition. For additional hash functions see the box at the bottom of the page.

| Algorithm | Output size (bits) | Internal state size | Block size | Length size | Word size | Collision resistance (complexity) | Preimage resistance (complexity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAVAL | 256/224/192/160/128 | 256 | 1024 | 64 | 32 | Yes | |

| MD2 | 128 | 384 | 128 | No | 8 | Almost | |

| MD4 | 128 | 128 | 512 | 64 | 32 | Yes (2^8)[10] | With flaws (2^102)[11] |

| MD5 | 128 | 128 | 512 | 64 | 32 | Yes (2^5) | No |

| PANAMA | 256 | 8736 | 256 | No | 32 | Yes | |

| RadioGatún | Arbitrarily long | 58 words | 3 words | No | 1-64 | No | |

| RIPEMD | 128 | 128 | 512 | 64 | 32 | Yes | |

| RIPEMD-128/256 | 128/256 | 128/256 | 512 | 64 | 32 | No | |

| RIPEMD-160/320 | 160/320 | 160/320 | 512 | 64 | 32 | No | |

| SHA-0 | 160 | 160 | 512 | 64 | 32 | Yes (2^39)[12] | |

| SHA-1 | 160 | 160 | 512 | 64 | 32 | With flaws (2^63)[13] | No |

| SHA-256/224 | 256/224 | 256 | 512 | 64 | 32 | No | No |

| SHA-512/384 | 512/384 | 512 | 1024 | 128 | 64 | No | No |

| Tiger(2)-192/160/128 | 192/160/128 | 192 | 512 | 64 | 64 | No | |

| WHIRLPOOL | 512 | 512 | 512 | 256 | 8 | No |

Note: The internal state here means the "internal hash sum" after each compression of a data block. Most hash algorithms also internally use some additional variables such as length of the data compressed so far since that is needed for the length padding in the end. See the Merkle-Damgård construction for details.

[edit] See also

- Avalanche effect

- MD5CRK

- Message authentication code

- Keyed-hash message authentication code

- CRHF - Collision Resistant Hash Functions.

- UOWHF - Universal One Way Hash Functions.

- CRYPTREC and NESSIE - Projects which recommend hash functions.

- PGP word list

- Template:User committed identity for instructions on how to create a hash for Wikipedia.

[edit] References

- ^ The proof is trivial: any algorithm that finds a collision for the concatenated hash function has obviously found a collision for both component functions.

- ^ More generally, if an attack can produce a collision in one hash function's internal state, attacking the combined construction is only as difficult as a birthday attack against the other function(s).

- ^ Joux, Antoine. Multicollisions in Iterated Hash Functions. Application to Cascaded Constructions. LNCS 3152/2004, pages 306-316 Full text.

- ^ Alexander Sotirov, Marc Stevens, Jacob Appelbaum, Arjen Lenstra, David Molnar, Dag Arne Osvik, Benne de Weger, MD5 considered harmful today: Creating a rogue CA certificate, accessed March 29, 2009

- ^ Xiaoyun Wang, Yiqun Lisa Yin, and Hongbo Yu, Finding Collisions in the Full SHA-1

- ^ Bruce Schneier, Cryptanalysis of SHA-1 (summarizes Wang et al. results and their implications)

- ^ Shai Halevi, Hugo Krawczyk, Update on Randomized Hashing

- ^ Shai Halevi and Hugo Krawczyk, Randomized Hashing and Digital Signatures

- ^ NIST.gov - Computer Security Division - Computer Security Resource Center

- ^ http://www.infosec.sdu.edu.cn/uploadfile/papers/Cryptanalysis%20of%20the%20Hash%20Functions%20MD4%20and%20RIPEMD.pdf

- ^ http://www.nis-summer-school.eu/presentations/bart_preneel_lecture.pdf

- ^ http://www.infosec.sdu.edu.cn/paper/sha0-crypto-author-new.pdf

- ^ Schneier on Security: New Cryptanalytic Results Against SHA-1

[edit] Further reading

- Bruce Schneier. Applied Cryptography. John Wiley & Sons, 1996. ISBN 0-471-11709-9.

[edit] External links

- The Hash function lounge — a list of hash functions and known attacks, by Paulo Barreto

- What is a hash function? from RSA Laboratories

- Hash functions: Theory, attacks, and applications — a survey by Ilya Mironov (Microsoft Research)

- Helger Lipmaa's links on hash functions

- Diagrams explaining cryptographic hash functions

- An Illustrated Guide to Cryptographic Hashes by Steve Friedl

- Cryptanalysis of MD5 and SHA: Time for a New Standard by Bruce Schneier

- Hash collision Q&A

- MD5 Collision Generation

- Improved Collision Attack on Hash Function MD5, very technical.

- Attacking hash functions by poisoned messages (construction of multiple sensible Postscript messages with the same hash function)

- Two colliding PostScript files with the same size

- Two colliding executable files

- Password Hashing in PHP by James McGlinn at the PHP Security Consortium

- The code monkey's guide to cryptographic hashes by Val Henson, "in language that any programmer (and even some managers) can understand."

- File Hash for Windows with various algorithms

- HashTab Windows shell extension to display file hashes

- Sinfocol Hashes An online hash generator (crc16, crc32, md2, md4, md5, ntlm, mysql323, sha, ripemd, and forty four other algorithms)

- Free collision & hash reversal tool

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||