Rayleigh scattering

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Rayleigh scattering (named after Lord Rayleigh) is the elastic scattering of light or other electromagnetic radiation by particles much smaller than the wavelength of the light. It can occur when light travels in transparent solids and liquids, but is most prominently seen in gases.

Rayleigh scattering of sunlight in clear atmosphere is the main reason why the sky is blue: Rayleigh and cloud-mediated scattering contribute to diffuse light (direct light being sunrays). Rayleigh scattering is also responsible for the blue color of veins, and is a component of iris color.[citation needed]

For scattering by particles similar to or larger than a wavelength, see Mie theory or discrete dipole approximation (they apply to the Rayleigh regime as well).

Contents |

[edit] Small size parameter approximation

The size of a scattering particle is parametrized by the ratio x of its characteristic dimension r and wavelength λ:

.

.

Rayleigh scattering can be defined as scattering in the small size parameter regime  . Scattering from larger spherical particles is explained by the Mie theory for an arbitrary size parameter x. The Mie theory reduces to the Rayleigh approximation.

. Scattering from larger spherical particles is explained by the Mie theory for an arbitrary size parameter x. The Mie theory reduces to the Rayleigh approximation.

The amount of Rayleigh scattering that occurs for a beam of light is dependent upon the size of the particles and the wavelength of the light; in particular, the scattering coefficient, and hence the intensity of the scattered light, varies for small size parameter inversely with the fourth power of the wavelength.

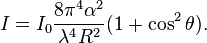

The intensity I of light scattered by a single small particle from a beam of unpolarized light of wavelength λ and intensity I0 is given by:

where R is the distance to the particle, θ is the scattering angle, n is the refractive index of the particle, and d is the diameter of the particle.

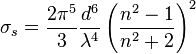

The angular distribution of Rayleigh scattering, governed by the (1+cos2θ) term, is symmetric in the plane normal to the incident direction of the light, and so the forward scatter equals the backwards scatter. Integrating over the sphere surrounding the particle gives the Rayleigh scattering cross section

The Rayleigh scattering coefficient for a group of scattering particles is the number of particles per unit volume N times the cross-section. As with all wave effects, for incoherent scattering the scattered powers add arithmetically, while for coherent scattering, such as if the particles are very near each other, the fields add arithmetically and the sum must be squared to obtain the total scattered power.

[edit] Rayleigh scattering from molecules

Rayleigh scattering from molecules is also possible. An individual molecule does not have a well-defined refractive index and diameter. Instead, a molecule has a polarizability α, which describes how much the electrical charges on the molecule will move in an electric field. In this case, the Rayleigh scattering intensity for a single particle is given by[1]

The amount of Rayleigh scattering from a single particle can also be expressed as a cross section σ. For example, the major constituent of the atmosphere, nitrogen, has a Rayleigh cross section of 5.1×10-31 m2 at a wavelength of 532 nm (green light).[2] This means that at atmospheric pressure, about a fraction 10-5 of light will be scattered for every meter of travel.

The strong wavelength dependence of the scattering (~λ-4) means that blue light is scattered much more readily than red light. In the atmosphere, this results in blue wavelengths being scattered to a greater extent than longer (red) wavelengths, and so one sees blue light coming from all regions of the sky. Direct radiation (by definition) is coming directly from the Sun. Rayleigh scattering is a good approximation to the manner in which light scattering occurs within various media for which scattering particles have a small size parameter.

[edit] Why is the sky blue?

When one looks at the sky during the day, rather than seeing the black of space, one sees light from Rayleigh scattering off the air. Rayleigh scattering is inversely proportional to the fourth power of wavelength, which means that the shorter wavelength of blue light will scatter more than the longer wavelengths of green and red light. This gives the sky a blue appearance. Conversely, when one looks towards the sun, one sees the colors that were not scattered away — the longer wavelengths such as red and yellow light. When the sun is near the horizon, the volume of air through which sunlight must pass is significantly greater than when the sun is high in the sky. Accordingly, the gradient from a red-yellow sun to the blue sky is considerably wider at sunrise and sunset.

Rayleigh scattering primarily occurs through light's interaction with air molecules. Some of the scattering can also be from aerosols of sulfate particles. For years following large Plinian eruptions, the blue cast of the sky is notably brightened due to the persistent sulfate load of the stratospheric eruptive gases. Another source of scattering is from microscopic density fluctuations, resulting from the random motion of the air molecules. A region of higher or lower density has a slightly different refractive index than the surrounding medium, and therefore it acts like a short-lived particle that can scatter light.

[edit] Biological effects

Rayleigh scattering is also the reason that veins are blue (venous blood is dark red), and is a component of iris color.[citation needed]

[edit] See also

- Raman scattering

- Optical phenomenon

- Dynamic light scattering

- Mie theory

- Tyndall effect

- Critical opalescence

- Marian Smoluchowski

- Rayleigh Criterion

- Aerial perspective

[edit] References

- ^ Rayleigh scattering at Hyperphysics

- ^ Maarten Sneep and Wim Ubachs, Direct measurement of the Rayleigh scattering cross section in various gases. Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer, 92, 293 (2005).

- C.F. Bohren, D. Huffman, Absorption and scattering of light by small particles, John Wiley, New York 1983. Contains a good description of the asymptotic behavior of Mie theory for small size parameter (Rayleigh approximation).

- Ditchburn, R.W. (1963). Light (2nd ed.). London: Blackie & Sons. pp. 582–585.

- Chakraborti, Sayan (September 2007). "Verification of the Rayleigh scattering cross section". American Journal of Physics 75 (9): 824−826. doi:.

- Ahrens, C. Donald (1994). Meteorology Today: an introduction to weather, climate, and the environment (5th ed.). St. Paul MN: West Publishing Company. pp. 88–89.