Condorcet method

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article is part of the Politics series |

| Electoral methods |

| Single-winner |

|

| Multiple-winner |

|

| Random selection |

| Politics portal |

A Condorcet method is any single-winner election method that meets the Condorcet criterion, that is, which always selects the Condorcet winner, the candidate who would beat each of the other candidates in a run-off election, if such a candidate exists. In modern examples, voters rank candidates in order of preference. There are then multiple, slightly differing methods for calculating the winner, due to the need to resolve circular ambiguities—including the Kemeny-Young method, Ranked Pairs, and the Schulze method.

Condorcet methods are named for the eighteenth century mathematician and philosopher Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas Caritat, the Marquis de Condorcet. Ramon Llull had devised one of the first Condorcet methods in 1299,[1] but this method is based on an iterative procedure rather than a ranked ballot.

[edit] Summary

- Rank the candidates in order (1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc.) of preference. Tie rankings are allowed, which express no preference between the tied candidates.

- Comparing each candidate on the ballot to every other, one at a time (pairwise), tally a "win" for the victor in each match.

- Sum these wins for all ballots cast. The candidate who has won every one of their pairwise contests is the most preferred, and hence the winner of the election.

- In the event of a tie, use a resolution method described below.

A particular point of interest is that it is possible for a candidate to be the most preferred overall without being the first preference of any voter. In a sense, the Condorcet method yields the "best compromise" candidate, the one that the largest majority will find to be least disagreeable, even if not their favorite.

[edit] Definition

A Condorcet method is a voting system that will always elect the Condorcet winner; this is the candidate whom voters prefer to each other candidate, when compared to them one at a time. This candidate can easily be found by conducting a series of pairwise comparisons, using the basic procedure described in this article. The family of Condorcet methods is also referred to collectively as Condorcet's method. A voting system that always elects the Condorcet winner when there is one is described by electoral scientists as a system that satisfies the Condorcet criterion.

In certain circumstances an election has no Condorcet winner. This occurs as a result of a kind of tie known as a 'majority rule cycle', described by Condorcet's paradox. The manner in which a winner is then chosen varies from one Condorcet method to another. Some Condorcet methods involve the basic procedure described below, coupled with a Condorcet completion method—a method used to find a winner when there is no Condorcet winner. Other Condorcet methods involve an entirely different system of counting, but are classified as Condorcet methods because they will still elect the Condorcet winner if there is one.

It is important to note that not all single winner, preferential voting systems are Condorcet methods. For example, neither instant-runoff voting nor the Borda count satisfies the Condorcet criterion.

[edit] Basic procedure

[edit] Voting

In a Condorcet election the voter ranks the list of candidates in order of preference. So, for example, the voter gives a '1' to their first preference, a '2' to their second preference, and so on. In this respect it is the same as an election held under non-Condorcet methods such as instant runoff voting or the single transferable vote. Some Condorcet methods allow voters to rank more than one candidate equally, so that, for example, the voter might express two first preferences rather than just one.

Usually, when a voter does not give a full list of preferences they are assumed, for the purpose of the count, to prefer the candidates they have ranked over all other candidates. Some Condorcet elections permit write-in candidates but, because this can be difficult to implement, software designed for conducting Condorcet elections often do not allow this option.

[edit] Finding the winner

The count is conducted by pitting every candidate against every other candidate in a series of imaginary one-on-one contests. The winner of each pairing is the candidate preferred by a majority of voters. The candidate preferred by each voter is taken to be the one in the pair that the voter ranks highest on their ballot paper. For example, if Alice is paired against Bob it is necessary to count both the number of voters who have ranked Alice higher than Bob, and the number who have ranked Bob higher than Alice. If Alice is preferred by more voters then she is the winner of that pairing. When all possible pairings of candidates have been considered, if one candidate beats every other candidate in these contests then they are declared the Condorcet winner. As noted above, if there is no Condorcet winner a further method must be used to find the winner of the election, and this mechanism varies from one Condorcet method to another.

[edit] Pairwise counting and matrices

Condorcet methods use pairwise counting. For each possible pair of candidates, one pairwise count indicates how many voters prefer one of the paired candidates over the other candidate, and another pairwise count indicates how many voters have the opposite preference. The counts for all possible pairs of candidates summarize all the preferences of all the voters.

Pairwise counts are typically displayed in matrices such as those below. In these matrices each row represents each candidate as a 'runner', while each column represents each candidate as an 'opponent'. The cells at the intersection of rows and columns each show the result of a particular pairwise comparison. Certain cells are left blank because it is impossible for a candidate to be compared with him or herself.

Imagine there is an election between four candidates: A, B, C and D. The first matrix below records the preferences expressed on a single ballot paper, in which the voter's preferences are (B, C, A, D); that is, the voter ranked B first, C second, A third, and D fourth. In the matrix a '1' indicates that the runner is preferred over the 'opponent', while a '0' indicates that the runner is defeated.

| Opponent | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | ||

| R u n n e r |

A | — | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| B | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | |

| C | 1 | 0 | — | 1 | |

| D | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | |

| A "1" indicates that the runner is preferred over the opponent; a '0' indicates that the runner is defeated. | |||||

Matrices of this kind are useful because they can be easily added together to give the overall results of an election. The sum of all ballots in an election is called the sum matrix. Suppose that in the imaginary election there are two other voters. Their preferences are (D, A, C, B) and (A, C, B, D). Added to the first voter, these ballots would give the following sum matrix:

| Opponent | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | ||

| R u n n e r |

A | — | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| B | 1 | — | 1 | 2 | |

| C | 1 | 2 | — | 2 | |

| D | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | |

When the sum matrix is found, the contest between each pair of candidates is considered. The number of votes for runner over opponent (runner,opponent) is compared with the number of votes for opponent over runner (opponent,runner). It is then possible to find the Condorcet winner. In the sum matrix above it can be seen that A is the Condorcet winner because A beats every other candidate. When there is no Condorcet winner Condorcet completion methods, such as Ranked Pairs and the Schulze method, use the information contained in the sum matrix to choose a winner.

Cells marked '—' in the matrices above have a numerical value of '0', but a dash is used since candidates are never preferred to themselves. The first matrix, that represents a single ballot, is inversely symmetric: (runner,opponent) is ¬(opponent,runner). Or (runner,opponent) + (opponent,runner) = 1. The sum matrix has this property: (runner,opponent) + (opponent,runner) = N for N voters, if all runners were fully ranked by each voter.

[edit] An example

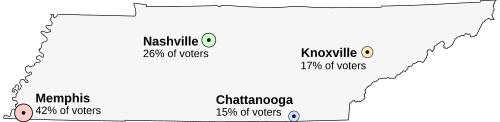

Imagine that Tennessee is having an election on the location of its capital. The population of Tennessee is concentrated around its four major cities, which are spread throughout the state. For this example, suppose that the entire electorate lives in these four cities, and that everyone wants to live as near the capital as possible.

The candidates for the capital are:

- Memphis, the state's largest city, with 42% of the voters, but located far from the other cities

- Nashville, with 26% of the voters, near the center of Tennessee

- Knoxville, with 17% of the voters

- Chattanooga, with 15% of the voters

The preferences of the voters would be divided like this:

| 42% of voters (close to Memphis) |

26% of voters (close to Nashville) |

15% of voters (close to Chattanooga) |

17% of voters (close to Knoxville) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

To find the Condorcet winner every candidate must be matched against every other candidate in a series of imaginary one-on-one contests. In each pairing the winner is the candidate preferred by a majority of voters. When results for every possible pairing have been found they are as follows:

| Pair | Winner |

|---|---|

| Memphis (42%) vs. Nashville (58%) | Nashville |

| Memphis (42%) vs. Chattanooga (58%) | Chattanooga |

| Memphis (42%) vs. Knoxville (58%) | Knoxville |

| Nashville (68%) vs. Chattanooga (32%) | Nashville |

| Nashville (68%) vs. Knoxville (32%) | Nashville |

| Chattanooga (83%) vs. Knoxville (17%) | Chattanooga |

The results can also be shown in the form of a matrix:

| A | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memphis | Nashville | Chattanooga | Knoxville | ||

| B | Memphis | [A] 58% [B] 42% |

[A] 58% [B] 42% |

[A] 58% [B] 42% |

|

| Nashville | [A] 42% [B] 58% |

[A] 32% [B] 68% |

[A] 32% [B] 68% |

||

| Chattanooga | [A] 42% [B] 58% |

[A] 68% [B] 32% |

[A] 17% [B] 83% |

||

| Knoxville | [A] 42% [B] 58% |

[A] 68% [B] 32% |

[A] 83% [B] 17% |

||

| Ranking: | 4th | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | |

- [A] indicates voters who preferred the candidate listed in the column caption to the candidate listed in the row caption

- [B] indicates voters who preferred the candidate listed in the row caption to the candidate listed in the column caption

- "Ranking" is found by repeatedly removing the Condorcet winner (it is not necessary to find these rankings).

Result: As can be seen from both of the tables above, Nashville beats every other candidate. This means that Nashville is the Condorcet winner. Nashville will thus win an election held under any possible Condorcet method.

While any Condorcet method will elect Nashville as the winner, if instead an election based on the same votes were held using first-past-the-post or instant-runoff voting, these systems would select Memphis[2] and Knoxville[3] respectively. This would occur despite the fact that most people would have preferred Nashville to either of those "winners". Condorcet methods make these preferences obvious rather than ignoring or discarding them.

[edit] Circular ambiguities

As noted above, sometimes an election has no Condorcet winner because there is no candidate who is preferred by voters to all other candidates. When this occurs the situation is known as a 'majority rule cycle', 'circular ambiguity' or 'circular tie'. This situation emerges when, once all votes have been added up, the preferences of voters with respect to some candidates form a circle in which every candidate is beaten by at least one other candidate. For example, if there are three candidates, Andrea, Carter and Delilah, there will be no Condorcet winner if voters prefer Andrea to Carter and Carter to Delilah, but also Delilah to Andrea. Depending on the context in which elections are held, circular ambiguities may or may not be a common occurrence. Nonetheless there is always the possibility of an ambiguity, and so every Condorcet method must be capable of determining a winner when this occurs. A mechanism for resolving an ambiguity is known as ambiguity resolution or Condorcet completion method.

Circular ambiguities arise as a result of the paradox of voting—the result of an election can be intransitive (forming a cycle) even though all individual voters expressed a transitive preference. In a Condorcet election it is impossible for the preferences of a single voter to be cyclical, because a voter must rank all candidates in order and can only rank each candidate once, but the paradox of voting means that it is still possible for a circular ambiguity to emerge.

The idealized notion of a political spectrum is often used to describe political candidates and policies. This means that each candidate can be defined by her position along a straight line, such as a line that goes from the most right wing candidates to the most left wing, with centrist candidates occupying the middle. Where this kind of spectrum exists and voters prefer candidates who are closest to their own position on the spectrum there is a Condorcet winner (Black's Single-Peakedness Theorem).

In Condorcet methods, as in most electoral systems, there is also the possibility of an ordinary tie. This occurs when two or more candidates tie with each other but defeat every other candidate. As in other systems this can be resolved by a random method such as the drawing of lots.

The method used to resolve circular ambiguities is the main difference between Condorcet methods. There are countless ways in which this can be done, but every Condorcet method involves ignoring the majorities expressed by voters in at least some pairwise matchings.

Condorcet methods fit within two categories:

- Two-method systems, which use a separate method to handle cases in which there is no Condorcet winner

- One-method systems, which use a single method that, without any special handling, always identifies the winner to be the Condorcet winner

[edit] Two-method systems

One family of Condorcet methods consists of systems that first conduct a series of pairwise comparisons and then, if there is no Condorcet winner, fall back to an entirely different, non-Condorcet method to determine a winner. The simplest such methods involve entirely disregarding the results of pairwise comparisons. For example, the Black method chooses the Condorcet winner if it exists, but uses the Borda count instead if there is an ambiguity (the method is named for Duncan Black).

A more sophisticated two-stage process is, in the event of an ambiguity, to use a separate voting system to find the winner but to restrict this second stage to a certain subset of candidates found by scrutinizing the results of the pairwise comparisons. Sets used for this purpose are defined so that they will always contain only the Condorcet winner if there is one, and will always, in any case, contain at least one candidate. Such sets include the

- Smith set: The smallest non-empty set of candidates in a particular election such that every candidate in the set can beat all candidates outside the set. It is easily shown that there is only one possible Smith set for each election.

- Schwartz set: This is the innermost unbeaten set, and is usually the same as the Smith set. It is defined as the union of all possible sets of candidates such that for every set:

- Every candidate inside the set is pairwise unbeatable by any other candidate outside the set (i.e., ties are allowed).

- No proper (smaller) subset of the set fulfills the first property.

- Landau set (or uncovered set or Fishburn set): the set of candidates, such that each member, for every other candidate (including those inside the set), either beats this candidate or beats a third candidate that itself beats the candidate that is unbeaten by the member.

One possible method is to apply instant-runoff voting to the candidates of the Smith set. This method has been described as 'Smith/IRV'.

[edit] Single-method systems

Some Condorcet methods use a single procedure that inherently meets the Condorcet criteria and, without any extra procedure, also resolves circular ambiguities when they arise. In other words, these methods do not involve separate procedures for different situations. Typically these methods base their calculations on pairwise counts. These methods include:

- Copeland's method: This simple method involves electing the candidate who wins the most pairwise matchings. However, it often produces a tie.

- Kemeny-Young method: This method ranks all the choices from most popular and second-most popular down to least popular.

- Minimax: Also called 'Simpson', 'Simpson-Kramer', and 'Simple Condorcet', this method chooses the candidate whose worst pairwise defeat is better than that of all other candidates. A refinement of this method involves restricting it to choosing a winner from among the Smith set; this has been called 'Smith/Minimax'.

- Ranked Pairs: This method is also known as 'Tideman', after its inventor Nicolaus Tideman.

- Schulze method: This method is also known as 'Schwartz sequential dropping' (SSD), 'cloneproof Schwartz sequential dropping' (CSSD), 'beatpath method', 'beatpath winner', 'path voting' and 'path winner'.

Ranked Pairs and Schulze are procedurally in some sense opposite approaches (although they very frequently give the same results):

- Ranked Pairs (and its variants) starts with the strongest defeats and uses as much information as it can without creating ambiguity.

- Schulze repeatedly removes the weakest defeat until ambiguity is removed.

Minimax could be considered as more "blunt" than either of these approaches, as instead of removing defeats it can be seen as immediately removing candidates by looking at the strongest defeats (although their victories are still considered for subsequent candidate eliminations).

[edit] Kemeny-Young method

The Kemeny-Young method considers every possible sequence of choices in terms of which choice might be most popular, which choice might be second-most popular, and so on down to which choice might be least popular. Each such sequence is associated with a Kemeny score that is equal to the sum of the pairwise counts that apply to the specified sequence. The sequence with the highest score is identified as the overall ranking, from most popular to least popular.

When the pairwise counts are arranged in a matrix in which the choices appear in sequence from most popular (top and left) to least popular (bottom and right), the winning Kemeny score equals the sum of the counts in the upper-right, triangular half of the matrix (shown here in bold on a green background).

| ... over Nashville | ... over Chattanooga | ... over Knoxville | ... over Memphis | |

| Prefer Nashville ... | - | 68 | 68 | 58 |

| Prefer Chattanooga ... | 32 | - | 83 | 58 |

| Prefer Knoxville ... | 32 | 17 | - | 58 |

| Prefer Memphis ... | 42 | 42 | 42 | - |

Calculating every Kemeny score requires considerable computation time in cases that involve more than a few choices. However, fast calculation methods based on integer programming allow a computation time in seconds for cases with as many as 40 choices.

[edit] Ranked Pairs

In the Ranked Pairs method, pairwise defeats are ranked (sorted) from strongest to weakest. Then each pairwise defeat is considered, starting with the strongest defeat. Defeats are "affirmed" (or "locked in") only if they do not create a cycle with the defeats already affirmed. Once completed, the affirmed defeats are followed to determine the winner of the overall election. In essence, Ranked Pairs treat each majority preference as evidence that the majority's more preferred alternative should finish over the majority's less preferred alternative, the weight of the evidence depending on the size of the majority.

[edit] Schulze method

The Schulze method resolves votes as follows:

- First, determine the Schwartz set (the innermost unbeaten set). If no defeats exist among the Schwartz set, then its members are the winners (plural only in the case of a tie, which must be resolved by another method).

- Otherwise, drop the weakest defeat information among the Schwartz set (i.e., where the number of votes favoring the defeat is the smallest). Determine the new Schwartz set, and repeat the procedure.

In other words, this procedure repeatedly throws away the weakest pairwise defeat within the top set, until finally the number of votes left over produce an unambiguous decision.

[edit] Defeat strength

Some pairwise methods—including minimax, Ranked Pairs, and the Schulze method—resolve circular ambiguities based on the relative strength of the defeats. There are different ways to measure the strength of each defeat, and these include considering "winning votes" and "margins":

- Winning votes: The number of votes on the winning side of a defeat.

- Margins: The number of votes on the winning side of the defeat, minus the number of votes on the losing side of the defeat.

If voters do not rank their preferences for all of the candidates, these two approaches can yield different results. Consider, for example, the following election:

| 45 voters | 11 voters | 15 voters | 29 voters |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. A | 1. B | 1. B | 1. C |

| 2. C | 2. B |

The pairwise defeats are as follows:

- B beats A, 55 to 45 (55 winning votes, a margin of 10 votes)

- A beats C, 45 to 44 (45 winning votes, a margin of 1 vote)

- C beats B, 29 to 26 (29 winning votes, a margin of 3 votes)

Using the winning votes definition of defeat strength, the defeat of B by C is the weakest, and the defeat of A by B is the strongest. Using the margins definition of defeat strength, the defeat of C by A is the weakest, and the defeat of A by B is the strongest.

Using winning votes as the definition of defeat strength, candidate B would win under minimax, Ranked Pairs and the Schulze method, but, using margins as the definition of defeat strength, candidate C would win in the same methods.

If all voters give complete rankings of the candidates, then winning votes and margins will always produce the same result. The difference between them can only come into play when some voters declare equal preferences amongst candidates, as occurs implicitly if they do not rank all candidates, as in the example above.

The choice between margins and winning votes is the subject of scholarly debate. Because all Condorcet methods always choose the Condorcet winner when one exists, the difference between methods only appears when cyclic ambiguity resolution is required. The argument for using winning votes follows from this: Because cycle resolution involves disenfranchising a selection of votes, then the selection should disenfranchise the fewest possible number of votes. When margins are used, the difference between the number of two candidates' votes may be small, but the number of votes may be very large—or not. Only methods employing winning votes satisfy Woodall's plurality criterion.

An argument in favour of using margins is the fact that the result of a pairwise comparison is decided by the presence of more votes for one side than the other and thus that it follows naturally to assess the strength of a comparison by this "surplus" for the winning side. Otherwise, changing only a few votes from the winner to the loser could cause a sudden large change from a large score for one side to a large score for the other. In other words, one could consider losing votes being in fact disenfranchised when it comes to ambiguity resolution with winning votes. Also, using winning votes, a vote containing ties (possibly implicitly in the case of an incompletely ranked ballot) doesn't have the same effect as a number of equally weighted votes with total weight equaling one vote, such that the ties are broken in every possible way (a violation of Woodall's symmetric-completion criterion), as opposed to margins.

Under winning votes, if two more of the "B" voters decided to vote "BC", the A->C arm of the cycle would be overturned and Condorcet would pick C instead of B. This is an example of "Unburying" or "Later does harm". The margin method would pick C anyway.

Under the margin method, if three more "BC" voters decided to "bury" C by just voting "B", the A->C arm of the cycle would be strengthened and the resolution strategies would end up breaking the C->B arm and giving the win to B. This is an example of "Burying". The winning votes method would pick B anyway.

The Requirement of Single-Peakedness (Economic Argument)

The Condorcet criteria requires preferences to be single-peaked; it is possible to rearrange policies or voting options such that each individual has a local maxima. The outcome of single-peakedness is one in which the median voter is always on the winning side as the preferences coincide with majority voting in this case. However a "voting paradox" arises, if preferences are not single-peaked then a problem of transitivity arises. This paradox is evidently visible with an example:

Policy X Y Z

Individual A 1 2 3

Individual B 3 1 2

Individual C 2 3 1

If numbers represent preferences such that 1>2>3 If we compare policy X and Y; then X is chosen (Individual A and C prefer X more than Y compared to B who prefers Y more) Thus in accordance to the Condorcet criteria, we compare the "winner" policy X with policy Z then policy Z is the chosen policy according to majority voting in this circumstance. However assume the same voting procedure was repeated; however this time comparing policy Y and Z first then pair wise comparisons allow us to conclude that Y will be chosen and when compared with policy X, then as before X is chosen. Thus with the same preferences and assuming same voting conditions two different results arise from majority voting. Preferences are intransitive.

[edit] Related terms

Other terms related to the Condorcet method are:

- Condorcet loser: the candidate who is less preferred than every other candidate in a pairwise matchup.

- Weak Condorcet winner: a candidate who beats or ties with every other candidate in a pairwise matchup. There can be more than one weak Condorcet winner.

- Weak Condorcet loser: a candidate who is defeated by or ties with every other candidate in a pairwise matchup. Similarly, there can be more than one weak Condorcet loser.

[edit] Condorcet Ranking Methods

Some Condorcet methods produce not just a single winner, but a ranking of all candidates from first to last place. A Condorcet ranking is a list of candidates with the property that the Condorcet winner (if one exists) comes first and the Condorcet loser (if one exists) comes last, and this holds recursively for the candidates ranked between them.

Methods that satisfy this property include:

[edit] Comparison with instant runoff and first-past-the-post (plurality)

There are circumstances, as in the example above, when both instant-runoff voting (IRV) and the 'first-past-the-post' plurality system will fail to pick the Condorcet winner. In cases where there is a Condorcet Winner, and where IRV does not choose it, a majority would by definition prefer the Condorcet Winner to the IRV winner. Proponents of the Condorcet criterion see it as a principal issue in selecting an electoral system. They see the Condorcet criterion as a natural extension of majority rule. Condorcet methods tend to encourage the selection of centrist candidates who appeal to the median voter. Here is an example that is designed to support IRV at the expense of Condorcet:

| 499 voters | 3 voters | 498 voters |

|---|---|---|

| 1. A | 1. B | 1. C |

| 2. B | 2. C | 2. B |

| 3. C | 3. A | 3. A |

B is preferred by a 501-499 majority to A, and by a 502-498 majority to C. So, according to the Condorcet criterion, B should win, despite the fact that very few voters rank B in first place. By contrast, IRV elects C and plurality elects A. Plurality becomes far worse than IRV and Condorcet as the number of candidates increases. The previous example could have been 334, 333, 333, and plurality would have awarded the win with 1/3 of the vote to a possible extremist.

The significance of this scenario, of two parties with strong support, and the one with weak support being the Condorcet winner, may be misleading, though, as it is a common mode in plurality voting systems (see Duverger's law), but much less likely to occur in Condorcet or IRV elections, which unlike Plurality voting, punish candidates who alienate a significant block of voters.

Here is an example that is designed to support Condorcet at the expense of IRV:

| 33 voters | 16 voters | 16 voters | 35 voters |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. A | 1. B | 1. B | 1. C |

| 2. B | 2. A | 2. C | 2. B |

| 3. C | 3. C | 3. A | 3. A |

B would win against either A or C by more than a 65-35 margin in a one-on-one election, but IRV eliminates B first, leaving a contest between the more "polar" candidates, A and C. Proponents of plurality voting state that their system is simpler than any other and more easily understood. All three systems are susceptible to tactical voting, but the types of tactics used and the frequency of strategic incentive differ in each method.

Even with Instant Runoff Voting, a true centrist has a 2/3 chance of winning against two extremists on either side, since the centrist needs only to beat one off them to get that candidate's votes and then beat the other. Examples promoting Condorcet, like that above, always show the 1/3 of cases where the Condorcet winner has fewer first choice votes than BOTH extremists.

Candidate Strategy with Condorcet vs Instant Runoff

Since Condorcet voting guarantees to elect the centrist candidate, if there is any winner, extremist candidates would soon learn that they can't win by telling the truth if Condorcet is used. Condorcet elections may promote candidates using insincere campaigning to sound like the most centrist of the bunch. Voters would then learn the winner's true motives once they are elected.

With Instant Runoff Voting, candidates have a larger incentive to campaign sincerely for the vote of like minded voters. Vote splitting is not the issue some claim it is, since votes will only be distributed to that nearby candidate, and the voters in that part of the spectrum are best able to judge, and are the only ones hurt if they judge wrong.

[edit] Potential for tactical voting

Like most voting methods, Condorcet methods are vulnerable to compromising. That is, voters can help avoid the election of a less-preferred candidate by insincerely raising the position of a more-preferred candidate on their ballot. However, Condorcet methods are only vulnerable to compromising when there is a majority rule cycle, or when one can be created.

Condorcet methods are vulnerable to burying. That is, voters can help a more-preferred candidate by insincerely lowering the position of a less-preferred candidate on their ballot. In general, this can be done by creating a false majority rule cycle that overrules a genuine pairwise defeat. Some Condorcet methods may be less vulnerable to the burying strategy than others.

[edit] Evaluation by criteria

Scholars of electoral systems often compare them using mathematically defined voting system criteria. The criteria which Condorcet methods satisfy vary from one Condorcet method to another. However, the Condorcet criterion implies the majority criterion; the Condorcet criterion is incompatible with independence of irrelevant alternatives, later-no-harm, the participation criterion, and the consistency criterion.

| Monotonic | Condorcet loser | Clone independence | Reversal symmetry | Polynomial time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schulze | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ranked Pairs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Minimax | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Nanson | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Kemeny-Young | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

[edit] Use of Condorcet voting

Condorcet methods are not currently in use in government elections anywhere in the world, but a Condorcet method known as Nanson's method was used in city elections in the U.S. town of Marquette, Michigan in the 1920s[4], and today Condorcet methods are used by a number of private organizations. Organizations which currently use some variant of the Condorcet method are:

- The Wikimedia Foundation uses the Schulze method to elect its Board of Trustees

- The Debian project uses the Schulze method for internal referenda and to elect its leader

- The Software in the Public Interest corporation uses the Schulze method for internal referenda and to elect its Board of Directors

- The Gentoo Foundation uses the Schulze method for internal referenda and to elect its Board of Trustees and its Council

- The Free State Project used Minimax for choosing its target state

- The uk.* hierarchy of Usenet

- The Student Society of the University of British Columbia uses Ranked Pairs for its executive elections.

- Kingman Hall, a student housing co-operative, uses the Schulze method for its elections

See also: Use of the Schulze method

[edit] Notes and references

- ^ G. Hägele and F. Pukelsheim (2001). "Llull's writings on electoral systems". Studia Lulliana 41: 3–38. http://www.math.uni-augsburg.de/stochastik/pukelsheim/2001a.html.

- ^ The largest bloc (plurality) of first place votes is 42% for Memphis; no other rankings are considered. So even though 58%—a true majority—would be inconvenienced by having the capital at the most remote location, Memphis wins.

- ^ Chattanooga (15%) is eliminated in the first round; votes transfer to Knoxville. Nashville (26%) eliminated in the second around; votes transfer to Knoxville. Knoxville wins with 58%.

- ^ See: Australian electoral reform and two concepts of representation

[edit] External links

- Ranked Pairs by Blake Cretney

- Condorcet Voting Calculator by Eric Gorr

- Alternative Voting Methods by James Green-Armytage

- Voting Systems by Paul E. Johnson

- Condorcet's Method By Rob Lanphier

- Accurate Democracy by Rob Loring

- Voting and Social Choice by Hervé Moulin. Demonstration and commentary on Condorcet method.

- CIVS, a free web poll service using the Condorcet method by Andrew Myers

- Software for computing Condorcet methods and STV by Jeffrey O'Neill

- A Strong No Show paradox is a common flaw in Condorcet voting correspondences by Joaquin Perez.

- Maximum Majority Voting by Ernest Prabhakar

- A New Monotonic and Clone-Independent Single-Winner Election Method (1, 2) by Markus Schulze