Capital punishment

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Capital punishment |

| Issues |

| Debate Religious views Wrongful execution |

| By country or region |

| Australia · Brazil · Canada China · France · Germany India · Iran · Iraq · Italy · Japan Malaysia · New Zealand Pakistan · Philippines Russia · Singapore Taiwan · United Kingdom United States · more |

| Methods |

| Decapitation · Electrocution Firing squad · Gas chamber Hanging · Lethal injection Shooting · Stoning more |

Capital punishment, the death penalty or execution, is the killing of a person by judicial process for retribution and incapacitation. Crimes that can result in a death penalty are known as capital crimes or capital offences. The term capital originates from Latin capitalis, literally "regarding the head" (Latin caput). Hence, a capital crime was originally one punished by the severing of the head.

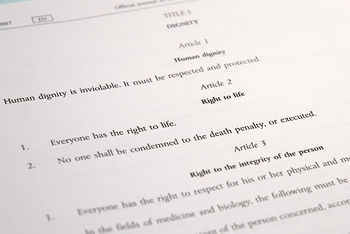

Capital punishment has been practiced in virtually every society, excluding those with state religious proscriptions against it. It is a matter of active controversy in various states, and positions can vary within a single political ideology or cultural region. A major exception is in Europe, where Article 2 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union prohibits the practice.[1]

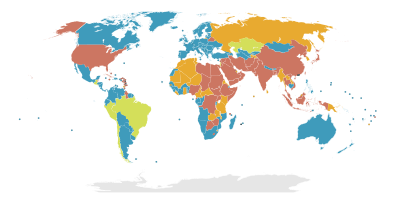

Today, most countries are considered by Amnesty International as abolitionists,[2] which allowed a vote on a resolution to the UN to promote the abolition of the death penalty.[3] But more than 60% of the worldwide population live in countries where executions take place in so far as the four most populous countries in the world (such as People's Republic of China, India, United States and Indonesia) apply the death penalty and are unlikely to abolish it soon.

Contents |

History

Execution of criminals and political opponents has been used by nearly all societies—both to punish crime and to suppress political dissent. In most places that practice capital punishment it is reserved for murder, espionage, treason, or as part of military justice. In some countries sexual crimes, such as rape, adultery, incest and sodomy, carry the death penalty, as do religious crimes such as apostasy in Islamic nations (the formal renunciation of the State religion). In many countries that use the death penalty, drug trafficking is also a capital offense. In China, human trafficking and serious cases of corruption are punished by the death penalty. In militaries around the world courts-martial have imposed death sentences for offenses such as cowardice, desertion, insubordination, and mutiny.[4]

The use of formal execution extends to the beginning of recorded history. Most historical records and various primitive tribal practices indicate that the death penalty was a part of their justice system. Communal punishment for wrongdoing generally included compensation by the wrongdoer, corporal punishment, shunning, banishment and execution. Within a small community, crimes were rare and murder was almost always a crime of passion.[citation needed] Moreover, most would hesitate to inflict death on a member of the community.[citation needed] For this reason, execution and even banishment were extremely rare. Usually, compensation and shunning were enough as a form of justice.[5]

However, these were viewed as not effective responses to crimes committed by outsiders. Consequently, even small crimes committed by outsiders were considered to be an assault on the community and were severely punished.[citation needed] The methods varied from beating and enslavement to executions. However, the response to crime committed by neighbouring tribes or communities included formal apology, compensation or blood feuds.

A blood feud or vendetta occurs when arbitration between families or tribes fails or an arbitration system is non-existent. This form of justice was common before the emergence of an arbitration system based on state or organised religion. It may result from crime, land disputes or a code of honour. "Acts of retaliation underscore the ability of the social collective to defend itself and demonstrate to enemies (as well as potential allies) that injury to property, rights, or the person will not go unpunished."[6] However, in practice, it is often difficult to distinguish between a war of vendetta and one of conquest.

Severe historical penalties include breaking wheel, boiling to death, flaying, slow slicing, disembowelment, crucifixion, impalement, crushing (including crushing by elephant), stoning, execution by burning, dismemberment, sawing, decapitation, scaphism, or necklacing.

Elaborations of tribal arbitration of feuds included peace settlements often done in a religious context and compensation system. Compensation was based on the principle of substitution which might include material (e.g. cattle, slave) compensation, exchange of brides or grooms, or payment of the blood debt. Settlement rules could allow for animal blood to replace human blood, or transfers of property or blood money or in some case an offer of a person for execution. The person offered for execution did not have to be an original perpetrator of the crime because the system was based on tribes, not individuals. Blood feuds could be regulated at meetings, such as the Viking things.[7] Systems deriving from blood feuds may survive alongside more advanced legal systems or be given recognition by courts (e.g. trial by combat). One of the more modern refinements of the blood feud is the duel.

In certain parts of the world, nations in the form of ancient republics, monarchies or tribal oligarchies emerged. These nations were often united by common linguistic, religious or family ties. Moreover, expansion of these nations often occurred by conquest of neighbouring tribes or nations. Consequently, various classes of royalty, nobility, various commoners and slave emerged. Accordingly, the systems of tribal arbitration were submerged into a more unified system of justice which formalised the relation between the different "classes" rather than "tribes". The earliest and most famous example is Code of Hammurabi which set the different punishment and compensation according to the different class/group of victims and perpetrators. The Torah (Jewish Law), also known as the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Christian Old Testament), lays down the death penalty for murder, kidnapping, magic, violation of the Sabbath, blasphemy, and a wide range of sexual crimes, although evidence suggests that actual executions were rare.[8] A further example comes from Ancient Greece, where the Athenian legal system was first written down by Draco in about 621 BC: the death penalty was applied for a particularly wide range of crimes, though Solon later repealed Draco's code and published new laws, retaining only Draco's homicide statutes.[9] The word draconian derives from Draco's laws. The Romans also used death penalty for a wide range of offenses.[10][11]

Islam on the whole accepts capital punishment.[12] The Abbasid Caliphs in Baghdad, such as Al-Mu'tadid, were often cruel in their punishments.[13] In the medieval Islamic world, there were a handful of sheikhs who were opposed to killing as a punishment.[citation needed] In the One Thousand and One Nights, also known as the Arabian Nights, the fictional storyteller Sheherazade is portrayed as being the "voice of sanity and mercy", with her philosophical position being generally opposed to punishment by death. She expresses this though several of her tales, including "The Merchant and the Jinni", "The Fisherman and the Jinni", "The Three Apples", and "The Hunchback".[14]

Similarly, in medieval and early modern Europe, before the development of modern prison systems, the death penalty was also used as a generalised form of punishment. For example, in 1700s Britain there were 222 crimes which were punishable by death, including crimes such as cutting down a tree or stealing an animal.[15] Thanks to the notorious Bloody Code, 18th century (and early 19th century) Britain was a hazardous place to live. For example, Michael Hammond and his sister, Ann, whose ages were given as 7 and 11, were reportedly hanged at King's Lynn on Wednesday, September 28, 1708 for theft. The local press did not, however, consider the executions of two children newsworthy.[16]

Although many are executed in China each year in the modern age, there was a time in Tang Dynasty China when the death penalty was abolished.[17] This was in the year 747, enacted by Emperor Taizong of Tang (r. 712–756), who before was the only person in China with the authority to sentence criminals to execution. Even then capital punishment was relatively infrequent, with only 24 executions in the year 730 and 58 executions in the year 736.[17] Two hundred years later there was a form of execution called Ling Chi (slow slicing), or death by/of a thousand cuts, used in China from roughly 900 CE to its abolition in 1905.

Despite its wide use, calls for reform were not unknown. The 12th century Sephardic legal scholar, Moses Maimonides, wrote, "It is better and more satisfactory to acquit a thousand guilty persons than to put a single innocent man to death." He argued that executing an accused criminal on anything less than absolute certainty would lead to a slippery slope of decreasing burdens of proof, until we would be convicting merely "according to the judge's caprice." His concern was maintaining popular respect for law, and he saw errors of commission as much more threatening than errors of omission.

The last several centuries have seen the emergence of modern nation-states. Almost fundamental to the concept of nation state is the idea of citizenship. This caused justice to be increasingly associated with equality and universality, which in Europe saw an emergence of the concept of natural rights. Another important aspect is that emergence of standing police forces and permanent penitential institutions. The death penalty became an increasingly unnecessary deterrent in prevention of minor crimes such as theft. The argument that deterrence, rather than retribution, is the main justification for punishment is a hallmark of the rational choice theory and can be traced to Cesare Beccaria whose well-known treatise On Crimes and Punishments (1764), condemned torture and the death penalty and Jeremy Bentham who twice critiqued the death penalty.[18] Additionally, in countries like Britain, law enforcement officials became alarmed when juries tended to acquit non-violent felons rather than risk a conviction that could result in execution.[citation needed] Moving executions there inside prisons and away from public view was prompted by official recognition of the phenomenon reported first by Beccaria in Italy and later by Charles Dickens and Karl Marx of increased violent criminality at the times and places of executions.

The 20th century was one of the bloodiest of the human history. Massive killing occurred as the resolution of war between nation-states. A large part of execution was summary execution of enemy combatants. Also, modern military organisations employed capital punishment as a means of maintaining military discipline. In the past, cowardice, absence without leave, desertion, insubordination, looting, shirking under enemy fire and disobeying orders were often crimes punishable by death. One method of execution since firearms came into common use has almost invariably been firing squad. Moreover, various authoritarian states—for example those with fascist or communist governments—employed the death penalty as a potent means of political oppression. Partly as a response to such excessive punishment, civil organisations have started to place increasing emphasis on the concept of human rights and abolition of the death penalty.

Among countries around the world, almost all European and many Pacific Area states (including Australia, New Zealand and Timor Leste), and Canada have abolished capital punishment. In Latin America, most states have completely abolished the use of capital punishment, while some countries, such as Brazil, allow for capital punishment only in exceptional situations, such as treason committed during wartime. The United States (the federal government and 35 of the states), Guatemala, most of the Caribbean and the majority of democracies in Asia (e.g. Japan and India) and Africa (e.g. Botswana and Zambia) retain it. South Africa, which is probably the most developed African nation, and which has been a democracy since 1994, does not have the death penalty. This fact is currently quite controversial in that country, due to the high levels of violent crime, including murder and rape.[19]

Capital punishment is a contentious issue in some cultures. Supporters of capital punishment argue that it deters crime, prevents recidivism, that it is less expensive than life imprisonment[20] and is an appropriate form of punishment for some crimes. Opponents of capital punishment argue that it has led to the execution of wrongfully convicted, that it discriminates against minorities and the poor, that it does not deter criminals more than life imprisonment, that it encourages a "culture of violence", that it is more expensive than life imprisonment,[20] and that it violates human rights. The death penalty, like some other governmental actions deemed to be in the public interest, has been particularly susceptible to the criticism that it may lead to perverse incentives and moral hazards. From the 1970s the deterrence hypothesis has been generally rejected by a consensus of justice policy researchers and academics, sometimes (data resolution allowing) in favor of a counter hypothesis of "brutalization" of public behavior.[21]

Movements towards humane execution

In early New England, public executions were a very solemn and sorrowful occasion, sometimes attended by large crowds, who also listened to a Gospel message[22] and remarks by local preachers and politicians. The Connecticut Courant records one such public execution on December 1, 1803, saying, "The assembly conducted through the whole in a very orderly and solemn manner, so much so, as to occasion an observing gentleman acquainted with other countries as well as this, to say that such an assembly, so decent and solemn, could not be collected anywhere but in New England."[23] Trends in most of the world have long been to move to less painful, or more humane, executions. France developed the guillotine for this reason in the final years of the 18th century while Britain banned drawing and quartering in the early 19th century. Hanging by turning the victim off a ladder or by dangling them from the back of a moving cart, which causes death by suffocation, was replaced by "hanging" where the subject is dropped a longer distance to dislocate the neck and sever the spinal cord. In the U.S., the electric chair and the gas chamber were introduced as more humane alternatives to hanging, but have been almost entirely superseded by lethal injection, which in turn has been criticised as being too painful. Nevertheless, some countries still employ slow hanging methods, beheading by sword and even stoning, although the latter is rarely employed.

Abolitionism

The death penalty was banned in China between 747 and 759. In England, a public statement of opposition was included in The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards, written in 1395. Sir Thomas More's Utopia, published in 1516, debated the benefits of the death penalty in dialogue form, coming to no firm conclusion. More recent opposition to the death penalty stemmed from the book of the Italian Cesare Beccaria Dei Delitti e Delle Pene ("On Crimes and Punishments"), published in 1764. In this book, Beccaria aimed to demonstrate not only the injustice, but even the futility from the point of view of social welfare, of torture and the death penalty. Influenced by the book, Grand Duke Leopold II of Habsburg, famous enlightened monarch and future Emperor of Austria, abolished the death penalty in the then-independent Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the first permanent abolition in modern times. On November 30, 1786, after having de facto blocked capital executions (the last was in 1769), Leopold promulgated the reform of the penal code that abolished the death penalty and ordered the destruction of all the instruments for capital execution in his land. In 2000 Tuscany's regional authorities instituted an annual holiday on November 30 to commemorate the event. The event is commemorated on this day by 300 cities around the world celebrating Cities for Life Day.

The Roman Republic banned capital punishment in 1849. Venezuela followed suit and abolished the death penalty in 1863 and San Marino did so in 1865. The last execution in San Marino had taken place in 1468. In Portugal, after legislative proposals in 1852 and 1863, the death penalty was abolished in 1867.

In the United Kingdom, it was abolished (except for treason) in 1973, the last execution having taken place in 1964. It was abolished totally in 1998. France abolished it in 1981, Canada abolished it in 1976 and Australia in 1985. In 1977, the United Nations General Assembly affirmed in a formal resolution that throughout the world, it is desirable to "progressively restrict the number of offenses for which the death penalty might be imposed, with a view to the desirability of abolishing this punishment".[24]

In the United States, Michigan was the first state to ban the death penalty, on May 18, 1846.[25] Currently, as of March 18, 2009, 15 states of the U.S. and the District of Columbia ban capital punishment, including New Mexico. [5]

The latest countries about to abolish the death penalty de facto for all crimes were Burundi, announced on November 22, 2008[26] and South Korea in practice on December 31, 2007 after ten years of disuse. The latest to abolish executions de jure was Argentina.

Contemporary use

Global distribution

|

||||||

| Criminal procedure | ||||||

| Criminal trials and convictions | ||||||

| Rights of the accused | ||||||

| Fair trial · Speedy trial Jury trial · Counsel Presumption of innocence Exclusionary rule1 Self-incrimination Double jeopardy2 |

||||||

| Verdict | ||||||

| Conviction · Acquittal Not proven3 Directed verdict |

||||||

| Sentencing | ||||||

| Mandatory · Suspended Custodial Dangerous offender4, 5 Capital punishment Execution warrant Cruel and unusual punishment |

||||||

| Post-sentencing | ||||||

| Parole · Probation Tariff6 · Life licence6 Miscarriage of justice Exoneration · Pardon |

||||||

| Related areas of law | ||||||

| Criminal defenses Criminal law · Evidence Civil procedure |

||||||

| Portals | ||||||

| Law · Criminal justice | ||||||

|

||||||

Since World War II there has been a consistent trend towards abolishing the death penalty. In 1977, 16 countries were abolitionist. As of February 1, 2009, 92 countries had abolished capital punishment, 10 had done so for all offences except under special circumstances, and 36 had not used it for at least 10 years or under a moratorium. Fifty-nine actively retained the death penalty.[27]

At least 3,000 people (and probably considerably more) were sentenced to death during 2007, and at the end of the year around 25,000 were on death row, with Pakistan and the USA accounting for about half this figure. China carries out by far the greatest number of executions: Amnesty International has confirmed at least 470 during 2007, but the true figure has been estimated at up to 6,000. Outside China, at least 800 people were put to death in 23 countries during 2007, with Iran, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Iraq and the USA the main contributors. Iran, Saudi Arabia and Yemen executed people for crimes committed when they were juveniles, in contravention of international law.[28]

Executions are known to have been carried out in the following countries in 2007:[28]

- Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Belarus, Botswana, China, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Japan, Kuwait, Libya, North Korea, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, USA, Vietnam, Yemen.

In 2007 the largest number of verifiable executions were carried out in the six countries listed below (with the exception of the US, the figures are believed to be under-estimates):

Most Executions carried out in 2007

| Country | Number | Executions per million people in country |

|---|---|---|

| China | 470+ (other sources est. 5,000)1 | 0.36+ (other sources est. 3.78)1 |

| Iran | 317+ | 4.50+ |

| Saudi Arabia | 143+ | 5.18+ |

| Pakistan | 135+ | 0.78+ |

| USA | 42 | 0.14 |

| Iraq | 33+ | 1.13+ |

| 1.Based on a combination of published and anecdotal evidence, Dui Hua foundation suggests the real tally in China may be as high as 5,000 (3.78 per million people)[29] | ||

In 2008 the worldwide execution rate was 2,390, with China responsible for executing approximately 1,740, Iran 342, Saudia Arabia 102, Pakistan 36, the United States 37, and Japan 15.[30]

The use of the death penalty is becoming increasingly restrained in retentionist countries. Singapore, Japan and the U.S. are the only fully developed countries that have retained the death penalty. The death penalty was overwhelmingly practiced in poor and authoritarian states, which often employed the death penalty as a tool of political oppression. During the 1980s, the democratisation of Latin America swelled the rank of abolitionist countries. This was soon followed by the fall of communism in Central and Eastern Europe, which then aspired to enter the EU. In these countries, the public support for the death penalty varies but it is decreasing.[31] The European Union and the Council of Europe both strictly require member states not to practice the death penalty (see Capital punishment in Europe). On the other hand, rapid industrialisation in Asia has been increasing the number of developed retentionist countries. In these countries, the death penalty enjoys strong public support, and the matter receives little attention from the government or the media. This trend has been followed by some African and Middle Eastern countries where support for the death penalty is high.

Some countries have resumed practicing the death penalty after having suspended executions for long periods. The United States suspended executions in 1972 but resumed them in 1977; there was no execution in India between 1995 and 2004; and Sri Lanka recently declared an end to its moratorium on the death penalty, although it has not yet performed any executions. The Philippines re-introduced the death penalty in 1993 after abolishing it in 1987, but abolished it again in 2006.

Execution for drug-related offenses

Several countries around the world execute offenders for drug-related crimes. Human rights activists have heavily criticised this.[32] Following the execution of an Australian in Singapore for drug smuggling, Australian prime minister John Howard stated that "the punishment certainly did not fit the crime".

The following is a list of countries with statutory provisions for the death penalty for drug-related offenses.

![]() United States (Although Federal Law mandates execution for certain drug offenses, no one is on death row for such offenses)

United States (Although Federal Law mandates execution for certain drug offenses, no one is on death row for such offenses)

![]() Iran

Iran

![]() Singapore

Singapore

![]() India (no execution carried out for such offenses)

India (no execution carried out for such offenses)

![]() Kuwait

Kuwait

![]() Bangladesh

Bangladesh

![]() Indonesia

Indonesia

![]() Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia

![]() Pakistan

Pakistan

![]() Afghanistan

Afghanistan

![]() Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe

![]() Brunei

Brunei

![]() Vietnam

Vietnam

![]() Laos

Laos

![]() Iraq

Iraq

![]() Oman

Oman

In specific countries

Abolished for all offenses (92) Abolished for all offenses except under special circumstances (10) Retains, though not used for at least 10 years (32) Retains death penalty (64)* *Note that, while laws vary between U.S. states, it is considered retentionist because the federal death penalty is still in active use.

For further information about capital punishment in these countries or regions, see: Australia · Canada · People's Republic of China (excluding Hong Kong and Macau) · Europe · India · Iran · Iraq · Japan · New Zealand ·Pakistan· Philippines · Russia · Singapore · Taiwan · United Kingdom · United States

Juvenile offenders

The death penalty for juvenile offenders (criminals aged under 18 years at the time of their crime) has become increasingly rare. Since 1990, nine countries have executed offenders who were juveniles at the time of their crimes: China, D.R. Congo, Iran, Nigeria, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, the United States and Yemen.[33] China, Pakistan, the United States and Yemen have since raised the minimum age to 18.[34] Amnesty International has recorded 61 verified executions since then, in several countries, of both juveniles and adults who had been convicted of committing their offenses as juveniles.[35] China does not allow for the execution of those under 18, but child executions have reportedly taken place.[36] The United States Supreme Court abolished capital punishment for offenders under the age of 16 in Thompson v. Oklahoma (1988), and for all juveniles in Roper v. Simmons (2005). Between 2005 and May 2008, Iran, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sudan and Yemen were reported to have executed child offenders, the most being from Iran.[37]

Starting in 1642 within British America, an estimated 365[38] juvenile offenders were executed by the states and federal government of the United States.[39] In 2002, the United States Supreme Court declared unconstitutional the execution of individuals with mental retardation.[40]

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which forbids capital punishment for juveniles under article 37(a), has been signed by all countries and ratified, except for Somalia and the United States.[41] The UN Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights maintains that the death penalty for juveniles has become contrary to a jus cogens of customary international law. A majority of countries are also party to the U.N. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (whereas under Article 6.5 also states that "Sentence of death shall not be imposed for crimes committed by persons below eighteen years of age...").

In Japan, the minimum age for the death penalty are 18 as mandated by the internationals standars. But under Japanese law, anyone under 20 is considered a juvenile. There are three men currently on death row for crimes they committed at age 18 or 19.

Iran and child executions

Iran, despite its ratification of the Convention on the Rights of the Child and International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, is currently the world's biggest executioner of child offenders, for which it has received international condemnation; the country's record is the focus of the Stop Child Executions Campaign.

Iran accounts for two-thirds of the global total of such executions, and currently has roughly 140 people on death row for crimes committed as juveniles (up from 71 in 2007).[42][43] The recent executions of Mahmoud Asgari, Ayaz Marhoni and Makwan Moloudzadeh became international symbols of Iran's child capital punishment and the flawed Iranian judicial system that hands down such sentences.[44][45]

Somalia

There is evidence that child executions are taking place in the parts of Somalia controlled by the Islamic Courts Union. In October, 2008, a girl, Aisho Ibrahim Dhuhulow was buried up to her neck at a football stadium, then stoned to death in front of more than 1,000 people. The stoning occurred after she had allegedly pleaded guilty to adultery in a shari`ah court in Kismayo, a city controlled by Islamist insurgents. According to the insurgents she had stated that she wanted shari`ah law to apply.[46]

However, other sources state that the victim had been crying, that she begged for mercy and had to be forced into the hole before being buried up to her neck in the ground.[47] Amnesty International later learned that the girl was in fact 13 years old (i.e. a child) and had been arrested by the al-Shabab militia after she had reported being gang-raped by three men.[48]

Methods

Methods of execution include electrocution, the firing squad or other sorts of shooting, stoning in Islamic countries, the gas chamber, hanging, and lethal injection.

Controversy and debate

Capital punishment is often the subject of controversy. Opponents of the death penalty argue that it has led to the execution of innocent people, that life imprisonment is an effective and less expensive substitute,[20] that it discriminates against minorities and the poor, and that it violates the criminal's right to life. Supporters believe that the penalty is justified for murderers by the principle of retribution, that life imprisonment is not an equally effective deterrent, and that the death penalty affirms the right to life by punishing those who violate it in the strictest form.

Wrongful executions

"Wrongful execution" is a miscarriage of justice occurring when an innocent person is put to death by capital punishment.[49] Many people have been proclaimed innocent victims of the death penalty.[50][51][52] Some have claimed that as many as 39 executions have been carried out in the U.S. in face of compelling evidence of innocence or serious doubt about guilt. Newly-available DNA evidence has allowed the exoneration of more than 15 death row inmates since 1992 in the U.S.,[53] but DNA evidence is only available in a fraction of capital cases. In the UK, reviews prompted by the Criminal Cases Review Commission have resulted in one pardon and three exonerations with compensation paid for people executed between 1950 and 1953, when the execution rate in England and Wales averaged 17 per year.

Public opinion

Support for the death penalty varies. Both in abolitionist and retentionist democracies, the government's stance often has wide public support and receives little attention by politicians or the media. In some abolitionist countries, the majority of the public supports or has supported the death penalty. Abolition was often adopted due to political change, as when countries shifted from authoritarianism to democracy, or when it became an entry condition for the European Union. The United States is a notable exception: some states have had bans on capital punishment for decades (the earliest is Michigan, where it was abolished in 1847), while others actively use it today. The death penalty there remains a contentious issue which is hotly debated. Elsewhere, however, it is rare for the death penalty to be abolished as a result of an active public discussion of its merits.

In abolitionist countries, debate is sometimes revived by particularly brutal murders, though few countries have brought it back after abolishing it. However, a spike in serious, violent crimes, such as murders or terrorist attacks, has prompted some countries (such as Sri Lanka and Jamaica) to effectively end the moratorium on the death penalty. In retentionist countries, the debate is sometimes revived when a miscarriage of justice has occurred, though this tends to cause legislative efforts to improve the judicial process rather than to abolish the death penalty.

A Gallup International poll from 2000 said that "Worldwide support was expressed in favor of the death penalty, with just more than half (52%) indicating that they were in favour of this form of punishment." A number of other polls and studies have been done in recent years with various results

In a poll completed by Gallup in October 2008, 64% of Americans supported the death penalty for persons convicted of murder, while 30% were against and 5% did not have an opinion.[54]

In the U.S., surveys have long shown a majority in favor of capital punishment. An ABC News survey in July 2006 found 65 percent in favour of capital punishment, consistent with other polling since 2000.[55] About half the American public says the death penalty is not imposed frequently enough and 60 percent believe it is applied fairly, according to a Gallup poll from May 2006.[56] Yet surveys also show the public is more divided when asked to choose between the death penalty and life without parole, or when dealing with juvenile offenders.[57] Roughly six in 10 tell Gallup they do not believe capital punishment deters murder and majorities believe at least one innocent person has been executed in the past five years.[58]

International organisations

The United Nations introduced a resolution during the General Assembly's 62nd sessions in 2007 calling for a universal ban.[59][60] The approval of a draft resolution by the Assembly’s third committee, which deals with human rights issues, voted 99 to 52, with 33 abstentions, in favour of the resolution on November 15, 2007 and was put to a vote in the Assembly on December 18.[61][62][63] Again in 2008, a large majority of states from all regions adopted a second resolution calling for a moratorium on the use of the death penalty in the UN General Assembly (Third Committee) on November 20. 105 countries voted in favour of the draft resolution, 48 voted against and 31 abstained. A range of amendments proposed by a small minority of pro-death penalty countries were overwhelmingly defeated. It had in 2007 passed a non-binding resolution (by 104 to 54, with 29 abstentions) by asking its member states for "a moratorium on executions with a view to abolishing the death penalty".[64]

A number of regional conventions prohibit the death penalty, most notably, the Sixth Protocol (abolition in time of peace) and the Thirteenth Protocol (abolition in all circumstances) to the European Convention on Human Rights. The same is also stated under the Second Protocol in the American Convention on Human Rights, which, however has not been ratified by all countries in the Americas, most notably Canada and the United States. Most relevant operative international treaties do not require its prohibition for cases of serious crime, most notably, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. This instead has, in common with several other treaties, an optional protocol prohibiting capital punishment and promoting its wider abolition.[65]

Several international organisations have made the abolition of the death penalty (during time of peace) a requirement of membership, most notably the European Union (EU) and the Council of Europe. The EU and the Council of Europe are willing to accept a moratorium as an interim measure. Thus, while Russia is a member of the Council of Europe, and practices the death penalty in law, it has not made public use of it since becoming a member of the Council. Other states, while having abolished de jure the death penalty in time of peace and de facto in all circumstances, have not ratified Protocol no.13 yet and therefore have no international obligation to refrain from using the death penalty in time of war or imminent threat of war (Armenia, Italy, Latvia, Poland and Spain[66]). France is the most recent to ratify it, on October 10, 2007, with an effective date of February 1, 2008.[67][68]

Turkey has recently, as a move towards EU membership, undergone a reform of its legal system. Previously there was a de facto moratorium on death penalty in Turkey as the last execution took place in 1984. The death penalty was removed from peacetime law in August 2002, and in May 2004 Turkey amended its constitution in order to remove capital punishment in all circumstances. It ratified Protocol no. 13 to the European Convention on Human Rights in February 2006. As a result, Europe is a continent free of the death penalty in practice, all states but Russia, which has entered a moratorium, having ratified the Sixth Protocol to the European Convention on Human Rights, with the sole exception of Belarus, which is not a member of the Council of Europe. The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe has been lobbying for Council of Europe observer states who practice the death penalty, the U.S. and Japan, to abolish it or lose their observer status. In addition to banning capital punishment for EU member states, the EU has also banned detainee transfers in cases where the receiving party may seek the death penalty.[citation needed]

Among non-governmental organisations (NGOs), Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch are noted for their opposition to capital punishment. A number of such NGOs, as well as trade unions, local councils and bar associations formed a World Coalition Against the Death Penalty in 2002.

Religious views

Buddhism

There is disagreement among Buddhists as to whether or not Buddhism forbids the death penalty. The first of the Five Precepts (Panca-sila) is to abstain from destruction of life. Chapter 10 of the Dhammapada states:

- Everyone fears punishment; everyone fears death, just as you do. Therefore do not kill or cause to kill. Everyone fears punishment; everyone loves life, as you do. Therefore do not kill or cause to kill.

Chapter 26, the final chapter of the Dhammapada, states, "Him I call a brahmin who has put aside weapons and renounced violence toward all creatures. He neither kills nor helps others to kill." These sentences are interpreted by many Buddhists (especially in the West) as an injunction against supporting any legal measure which might lead to the death penalty. However, as is often the case with the interpretation of scripture, there is dispute on this matter. Historically, most states where the official religion is Buddhism have imposed capital punishment for some offenses. One notable exception is the abolition of the death penalty by the Emperor Saga of Japan in 818. This lasted until 1165, although in private manors executions continued to be conducted as a form of retaliation. Japan still imposes the death penalty, although some recent justice ministers have refused to sign death warrants, citing their Buddhist beliefs as their reason.[69] Other Buddhist-majority states vary in their policy. For example, Bhutan has abolished the death penalty, but Thailand still retains it, although Buddhism is the official religion in both.

Judaism

The official teachings of Judaism approve the death penalty in principle but the standard of proof required for application of death penalty is extremely stringent, and in practice, it has been abolished by various Talmudic decisions, making the situations in which a death sentence could be passed effectively impossible and hypothetical. "Forty years before the destruction" of the Temple in Jerusalem in 70 AD, i.e. in 30 AD, the Sanhedrin effectively abolished capital punishment, making it a hypothetical upper limit on the severity of punishment, fitting in finality for God alone to use, not fallible people.[70]

In law schools everywhere, students read the famous quotation from the 12th century legal scholar, Maimonides,

- "It is better and more satisfactory to acquit a thousand guilty persons than to put a single innocent one to death."

Maimonides argued that executing a defendant on anything less than absolute certainty would lead to a slippery slope of decreasing burdens of proof, until we would be convicting merely "according to the judge's caprice." Maimonides was concerned about the need for the law to guard itself in public perceptions, to preserve its majesty and retain the people's respect.[71]

Islam

Scholars of Islam hold it to be permissible but the victim or the family of the victim has the right to pardon. In Islamic jurisprudence (Fiqh), to forbid what is not forbidden is forbidden. Consequently, it is impossible to make a case for abolition of the death penalty, which is explicitly endorsed.

Sharia Law or Islamic law may require capital punishment, there is great variation within Islamic nations as to actual capital punishment. Apostasy in Islam and stoning to death in Islam are controversial topics. Furthermore, as expressed in the Qur'an, capital punishment is condoned. Although the Qur'an prescribes the death penalty for several hadd (fixed) crimes—including rape—murder is not among them. Instead, murder is treated as a civil crime and is covered by the law of qisas (retaliation), whereby the relatives of the victim decide whether the offender is punished with death by the authorities or made to pay diyah (wergild) as compensation.[72]

"If anyone kills person - unless it be for murder or for spreading mischief in the land - it would be as if he killed all people. And if anyone saves a life, it would be as if he saved the life of all people" (Qur'an 5:32). "Spreading mischief in the land" can mean many different things, but is generally interpreted to mean those crimes that affect the community as a whole, and destabilise the society. Crimes that have fallen under this description have included: (1) Treason, when one helps an enemy of the Muslim community; (2) Apostasy, when one leaves the faith; (3) Land, sea, or air piracy; (4) Rape; (5) Adultery; (6) Homosexual behaviour.[73]

Christianity

Although some interpret that Jesus' teachings condemn the death penalty in The Gospel of Luke and The Gospel of Matthew regarding Turning the other cheek, and John 8:7 in which Jesus intervenes in the stoning of an adulteress, rebuking the mob with the phrase "may he who is without sin cast the first stone", others consider Romans 13:3-4 to support it. Also, Leviticus 20:2-27 has a whole list of situations in which execution is supported. Christian positions on this vary.[74] The sixth commandment (fifth in the Roman Catholic and Lutheran churches) is preached as 'Thou shalt not kill' by some denominations and as 'Thou shalt not murder' by others. As some denominations do not have a hard-line stance on the subject, Christians of such denominations are free to make a personal decision.[75]

Roman Catholic Church

In a June, 2004 memo to the U.S. Bishops, Pope Benedict XVI (then known as Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger) made this statement : "Not all moral issues have the same moral weight as abortion and euthanasia. There may be a legitimate diversity of opinion even among Catholics about waging war and applying the death penalty, but not however with regard to abortion and euthanasia." [76]

The Church has traditionally accepted capital punishment as per the theology of Thomas Aquinas (who accepted the death penalty as a necessary deterrent and prevention method, but not as a means of vengeance; see also Aquinas on the death penalty).

In Evangelium Vitae, the Church teaches that capital punishment should be avoided unless it is the only way to defend society from the offender in question, and that with today's penal system such a situation requiring an execution is either rare or non-existent.[77] The Catechism of the Catholic Church holds a similar view [78]

Anglican and Episcopalian

The Lambeth Conference of Anglican and Episcopalian bishops condemned the death penalty in 1988:

This Conference: ... 3. Urges the Church to speak out against: ... (b) all governments who practice capital punishment, and encourages them to find alternative ways of sentencing offenders so that the divine dignity of every human being is respected and yet justice is pursued;....[79]

United Methodist Church

The United Methodist Church, along with other Methodist churches, also condemns capital punishment, saying that it cannot accept retribution or social vengeance as a reason for taking human life.[80] The Church also holds that the death penalty falls unfairly and unequally upon marginalised persons including the poor, the uneducated, ethnic and religious minorities, and persons with mental and emotional illnesses.[81] The General Conference of the United Methodist Church calls for its bishops to uphold opposition to capital punishment and for governments to enact an immediate moratorium on carrying out the death penalty sentence.

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

In a 1991 social policy statement, the ELCA officially took a stand to oppose the death penalty. It states that revenge is a primary motivation for capital punishment policy and that true healing can only take place through repentance and forgiveness.[82]

The Southern Baptist Convention

In 2000 the Southern Baptist Convention updated Baptist Faith and Message. In it the convention officially sanctioned the use of capital punishment by the State. It said that it is the duty of the state to execute those guilty of murder and that God established capital punishment in the Noahic Covenant.

Other Protestants

Several key leaders early in the Protestant Reformation, including Martin Luther and John Calvin, followed the traditional reasoning in favour of capital punishment, and the Lutheran Church's Augsburg Confession explicitly defended it. Some Protestant groups have cited Genesis 9:5–6, Romans 13:3–4, and Leviticus 20:1–27 as the basis for permitting the death penalty.[83]

Mennonites, Church of the Brethren and Friends have opposed the death penalty since their founding, and continue to be strongly opposed to it today. These groups, along with other Christians opposed to capital punishment, have cited Christ's Sermon on the Mount (transcribed in Matthew Chapter 5–7) and Sermon on the Plain (transcribed in Luke 6:17–49). In both sermons, Christ tells his followers to turn the other cheek and to love their enemies, which these groups believe mandates nonviolence, including opposition to the death penalty.

Eastern Orthodox Christianity

Eastern Orthodox Christianity is against the death penalty, believing that killing is wrong in any circumstance.[citation needed]

Esoteric Christianity

The Rosicrucian Fellowship and many other Christian esoteric schools condemn capital punishment in all circumstances.[84][85]

In arts and media

Literature

- The Gospels describe the execution of Jesus Christ at length, and these accounts form the central story of the Christian faith. Depictions of the crucifixion are abundant in Christian art.

- Valerius Maximus' story of Damon and Pythias was long a famous example of fidelity. Damon was sentenced to death (the reader does not learn why) and his friend Pythias offered to take his place.

- "An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge" is a short story by Ambrose Bierce originally published in 1890. The story deals with the hanging of a Confederate sympathiser during the American Civil War.

- Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities ends in the climactic execution of the book's main character.

- Victor Hugo's The Last Day of a Condemned Man (Le Dernier Jour d'un condamné) describes the thoughts of a condemned man just before his execution; also notable is its preface, in which Hugo argues at length against capital punishment.

- Anaïs Nin's anthology Little Birds included an erotic depiction of a public execution.

- William Burroughs' novel Naked Lunch also included erotic and surreal depictions of capital punishment. In the obscenity trial against Burroughs, the defense claimed successfully that the novel was a form of anti-death-penalty argument, and therefore had redeeming political value.

- In The Chamber by John Grisham, a young lawyer tries to save his Klansman grandfather from being executed. The novel is noted for presentation of anti-death penalty materials.

- Bernard Cornwell's novel Gallows Thief is a whodunit taking place in early 19th century England, during the so-called "Bloody Code" a series of laws making several minor crimes capital offenses. The hero is a detective assigned to investigate the guilt of a condemned man, and the difficulties he encounters act as a harsh indictment of the draconian laws and the public's complacent attitude towards capital punishment.

- A Hanging, by George Orwell, tells the story of an execution that he witnessed while he served as a policeman in Burma in the 1920s. He wrote, "It is curious, but till that moment I had never realized what it means to destroy a healthy, conscious man. When I saw the prisoner step aside to avoid the puddle, I saw the mystery, the unspeakable wrongness, of cutting a life short when it is in full tide. This man was not dying, he was alive just as we were alive..."

- Discipline and Punish: The Birth of The Prison, by Michel Foucault deals with capital punishment relative to how torture has been eradicated for the most part, and punishment is now quick and painless. Foucault believes that punishment is now directed more toward the soul than toward the body.

- A Lesson Before Dying follows a wrongly convicted man on death row

Film, television, and theatre

- Capital punishment has been the basis of many motion pictures, including Seed, Dead Man Walking based on the book by Sister Helen Prejean, The Green Mile, The Life of David Gale and Dancer in the Dark.

- The stage play (and later film) The Exonerated by Erik Jensen and Jessica Blank

- The HBO series Oz focused on counter-perspectives for/against the death penalty.

- Prison Break is a 2005 television series, whose protagonist attempts to save his brother from execution by devising a plan that will help them escape from prison.

- The Film Let Him Have It Is the True Story of a Young Understood Male, who after being controversially accused, is executed by hanging.

Music

- "16 on Death Row", a song from 2Pac's Posthumous Album R U Still Down? (Remember Me)

- "Women's Prison", song from Loretta Lynn's Van Lear Rose album

- "25 Minutes to Go" is a song written by Shel Silverstein and sung by Johnny Cash At Folsom Prison and The Brothers Four.

- "The Mercy Seat" by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds (also performed by Johnny Cash) describes a man being executed via the electric chair who maintains his innocence until he is about to die, when he admits to his guilt.

- "Ride The Lightning" by Metallica is also about a man being executed via an electric chair, although he is not ultimately culpable, as through insanity or loss of autonomy.

- "Hallowed Be Thy Name" by Iron Maiden is about a man about be executed by hanging.

- In "Green Green Grass of Home", the singer who is apparently returning home is actually awaiting his execution.

- "Shock rock" star Alice Cooper will use three different methods of capital punishment for his stage shows. The three are the guillotine, the electric chair (retired) and hanging (first method, then retired, then used on the 2007 tour).

- Freedom Cry is an album of songs performed by condemned prisoners in Uganda, recorded by prisoners' rights charity African Prisons Project and available online.[86]

- "Gallows Pole" is a centuries old folk song, popularised by Lead Belly, which has seen several cover versions. Led Zeppelin covered the song in the 70's, and was subsequently revived by Page and Plant during their No Quarter acoustic tours.

- The Bee Gees song "I've Gotta Get a Message to You" deals with a man who is about to be executed who wants to get one last message to his wife.

- The song "The Man I Killed" by NOFX from their album Wolves in Wolves' Clothing is sung from the perspective of a death row inmate during his execution by lethal injection.

- Ellis Unit One - Steve Earle (from the movie, Dead Man Walking) is a movie that looks at capital punishment from the perspective of the jail guards.

- Dead Man Walking - Bruce Springsteen (from the movie, Dead Man Walking) is written from the perspective of the inmate about to be killed

See also

References

- ^ Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union

- ^ Amnesty International

- ^ moratorium on the death penalty]

- ^ "Shot at Dawn, campaign for pardons for British and Commonwealth soldiers executed in World War I". Shot at Dawn Pardons Campaign. http://www.shotatdawn.org.uk/. Retrieved on 2006-07-20.

- ^ So common was the practice of compensation that the word murder is derived from the French word mordre (bite) a reference to the heavy compensation one must pay for causing an unjust death. The "bite" one had to pay was used as a term for the crime itself: "Mordre wol out; that se we day by day." - Geoffrey Chaucer (1340–1400), The Canterbury Tales, The Nun’s Priest’s Tale, l. 4242 (1387-1400), repr. In The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, ed. Alfred W. Pollard, et al. (1898).

- ^ Translated from Waldmann, op.cit., p.147.

- ^ Lindow, op.cit. (primarily discusses Icelandic things).

- ^ Schabas, William (2002). The Abolition of the Death Penalty in International Law. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81491-X.

- ^ Greece, A History of Ancient Greece, Draco and Solon Laws

- ^ capital punishment, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Capital punishment in the Roman Empire

- ^ Islam and capital punishment

- ^ The Caliphate: Its Rise, Decline, and Fall., William Muir

- ^ Zipes, Jack David (1999), When Dreams Came True: Classical Fairy Tales and Their Tradition, Routledge, pp. 57–8, ISBN 0415921511

- ^ Almost invariably, however, sentences of death for property crimes were commuted to transportation to a penal colony or to a place where the felon was worked as an indentured servant/Michigan State University and Death Penalty Information Center

- ^ History of British judicial hanging

- ^ a b Benn, Charles. 2002. China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517665-0. Page 8.

- ^ "JSTOR: The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology (1973-)Vol. 74, No. 3 (Autumn, 1983), pp. 1033-1065". Northwestern University School of Law. 1983. http://www.jstor.org/pss/1143143. Retrieved on 2008-10-13.

- ^ "Definite no to Death Row - Asmal". http://www.iol.co.za/index.php?set_id=1&click_id=13&art_id=vn20080308081322646C403034/. Retrieved on 2008-03-08.

- ^ a b c "The High Cost of the Death Penalty". Death Penalty Focus. http://www.deathpenalty.org/article.php?id=42. Retrieved on 2008-06-27.

- ^ Discussion of Recent Deterrence Studies

- ^ Article from the Connecticut Courant (December 1, 1803)

- ^ The Execution of Caleb Adams, 2003

- ^ Death Penalty

- ^ See Caitlin pp. 420-422

- ^ http://www.gulf-times.com/site/topics/article.asp?cu_no=2&item_no=256152&version=1&template_id=39&parent_id=21 Burundi abolishes death penalty, outlaws gays and protects women

- ^ "Abolitionist and Retentionist Countries". Amnesty International. http://www.amnesty.org/en/death-penalty/abolitionist-and-retentionist-countries. Retrieved on 2008-06-10.

- ^ a b "Death Sentences and Executions in 2007". Amnesty International website. http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/ACT50/001/2008/en/b43a1e5a-ffea-11dc-b092-bdb020617d3d/act500012008eng.html. Retrieved on 2008-04-15.

- ^ Dui Hua estimates that around 5,000 people were executed in China in 2007. We can make this statement based on a combination of published and anecdotal evidence despite the fact that the Chinese government closely guards its statistics on capital punishment on the grounds of "state secrecy."

- ^ Les exécutions ont pratiquement doublé en 2008, selon Amnest

- ^ "International Polls & Studies". The Death Penalty Information Center. http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/article.php?did=2165. Retrieved on 2008-04-01.

- ^ Amnesty International- Articles-

* Iran flies in the face of global execution trend

*Singapore- Executions since december defy global trend

* India must establish a moratorium on executions

Kuwait: Death penalty: Sheik Talal Nasser Bin Nasser Al-Salah

* Three Australians spared death in bali

Saudi Arabia- Risk of imminent execution - ^ Juvenile executions (except US)

- ^ Amnesty International

- ^ Amnesty International

- ^ "Stop Child Executions! Ending the death penalty for child offenders". Amnesty International. 2004. http://web.amnesty.org/library/Index/ENGACT500152004. Retrieved on 2008-02-12.

- ^ HRW Report

- ^ Execution of Juveniles in the U.S. and other Countries

- ^ Rob Gallagher, Table of juvenile executions in British America/United States, 1642–1959

- ^ Supreme Court bars executing mentally retarded CNN.com Law Center. June 25, 2002

- ^ UNICEF, Convention of the Rights of the Child - FAQ: "The Convention on the Rights of the Child is the most widely and rapidly ratified human rights treaty in history. Only two countries, Somalia and the United States, have not ratified this celebrated agreement. Somalia is currently unable to proceed to ratification as it has no recognised government. By signing the Convention, the United States has signaled its intention to ratify, but has yet to do so."

- ^ Iranian activists fight child executions, Ali Akbar Dareini, Associated Press, September 17, 2008; accessed September 22, 2008.

- ^ Iran rapped over child executions, Pam O'Toole, BBC, June 27, 2007; accessed September 22, 2008.

- ^ Iran Does Far Worse Than Ignore Gays, Critics Say, Fox News, September 25, 2007; accessed September 20, 2008.

- ^ Iranian hanged after verdict stay; BBCnews.co.uk; 2007-12-06; Retrieved on 2007-12-06

- ^ "Somali woman executed by stoning". BBC News. 2008-10-27. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7694397.stm. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/7708169.stm

- ^ "Somalia: Girl stoned was a child of 13". Amnesty International. 2008-10-31. http://www.amnesty.org/en/for-media/press-releases/somalia-girl-stoned-was-child-13-20081031. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ^ Innocence and the Death Penalty

- ^ Capital Defense Weekly

- ^ Executed Innocents

- ^ Wrongful executions

- ^ The Innocence Project - News and Information: Press Releases

- ^ 2008 Gallup Death Penalty Poll

- ^ ABC News poll, "Capital Punishment, 30 Years On: Support, but Ambivalence as Well" (PDF, July 1, 2006)

- ^ Crime

- ^ [1] [2]

- ^ [3] [4]

- ^ Thomas Hubert (2007-06-29). "Journée contre la peine de mort : le monde décide!" (in French). Coalition Mondiale. http://www.worldcoalition.org/modules/news/article.php?storyid=10.

- ^ Amnesty International

- ^ "UN set for key death penalty vote". Amnesty International. 2007-12-09. http://www.amnesty.org/en/news-and-updates/news/un-set-key-death-penalty-vote-20071209. Retrieved on 2008-02-12.

- ^ Directorate of Communication - The global campaign against the death penalty is gaining momentum - Statement by Terry Davis, Secretary General of the Council of Europe

- ^ UN General Assembly - Latest from the UN News Centre

- ^ "U.N. Assembly calls for moratorium on death penalty". Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/topNews/idUSN1849885920071218.

- ^ "Second Optional Protocol to the ICCPR". Office of the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights. http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/ccpr-death.htm. Retrieved on 2007-12-08.

- ^ Amnesty International

- ^ "France abolishes the death penalty in all circumstances". Human Rights Education Associates. 2007-10-11. http://www.hrea.org/lists2/display.php?language_id=1&id=6155. Retrieved on 2008-02-13.

- ^ Directorate of Communication - France abolishes the death penalty in all circumstances

- ^ Japan hangs two more on death row (see also paragraph 11

- ^ Jerusalem Talmud (Sanhedrin 41 a)

- ^ Moses Maimonides, The Commandments, Neg. Comm. 290, at 269–271 (Charles B. Chavel trans., 1967).

- ^ capital punishment - Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ Capital Punishment in Islam

- ^ What The Christian Scriptures Say About The Death Penalty - Capital Punishmen

- ^ BBC - Religion & Ethics - Capital punishment: Introduction

- ^ Roman Catholic support for the death penalty

- ^ Papal encyclical, Evangelium Vitae, March 25, 1995

- ^ Assuming that the guilty party's identity and responsibility have been fully determined, the traditional teaching of the Church does not exclude recourse to the death penalty, if this is the only possible way of effectively defending human lives against the unjust aggressor.

- ^ Lambeth Conference of Anglican Bishops, 1988, Resolution 33, paragraph 3. (b), found at Lambeth Conference official website page. Accessed July 16, 2008.

- ^ The United Methodist Church: Capital Punishment

- ^ The United Methodist Church: Official church statements on capital punishment

- ^ ELCA Social Statement on the Death Penalty

- ^ http://www.equip.org/free/CP1303.htm http://www.equip.org/free/CP1304.htm

- ^ Heindel, Max (1910s), The Rosicrucian Philosophy in Questions and Answers - Volume II: Question no.33: Rosicrucian Viewpoint of Capital Punishment, ISBN 0-911274-90-1

- ^ The Rosicrucian Fellowship: Obsession, Occult Effects of Capital Punishment

- ^ Condemned Choirs from Luzira Prison, Uganda

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Capital punishment |

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Capital punishment |

- Correspondence with Jose Medellin, currently sitting on death row in Texas.

- About.com's Pros & Cons of the Death Penalty and Capital Punishment

- 1000+ Death Penalty links all in one place

- U.S. and 50 State DEATH PENALTY / CAPITAL PUNISHMENT LAW and other relevant links from Megalaw

- Updates on the death penalty generally and capital punishment law specifically

- Texas Department of Criminal Justice: list of executed offenders and their last statements

- Two audio documentaries covering execution in the United States: Witness to an Execution The Execution Tapes

- Article published in the Internationalist Review on the evolution of execution methods in the United States

- Answers.com entry on capital punishment

- ProCon.org website on death penalty Includes state laws, execution methods, candidate positions, pros and cons

Opposing

- World Coalition Against the Death Penalty

- Death Watch International International anti-death penalty campaign group

- Campaign to End the Death Penalty

- Anti-Death Penalty Information: includes a monthly watchlist of upcoming executions and death penalty statistics for the United States.

- The Death Penalty Information Center: Statistical information and studies

- Amnesty International - Abolish the death penalty Campaign: Human Rights organisation

- The Council of Europe (international organisation composed of 46 European States): activities and legal instruments against the death penalty

- European Union: Information on anti-death penalty policies

- IPS Inter Press Service International news on capital punishment

- Death Penalty Focus: American group dedicated to abolishing the death penalty

- Reprieve.org: United States based volunteer program for foreign lawyers, students, and others to work at death penalty defense offices

- American Civil Liberties Union: Demanding a Moratorium on the Death Penalty

- Catholics Against Capital Punishment: offers a Catholic perspective and provides resources and links

- National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

- Australian Coalition Against Death Penalty (ACADP) - human rights organisation for total abolition of Death Penalty, worldwide.

- NSW Council for Civil Liberties: an Australian organisation opposed to the Death Penalty in the Asian region

- Winning a war on terror: eliminating the death penalty

- 850+ Death Penalty Quotes

In favour

- Off2DR.com is an Interactive pro death penalty information resource & place for discussions

- Pro Death Penalty.com

- Pro Death Penalty Resource Page

- Capital Punishment - A Defense

- 119 Pro DP Links

- British National Party, A political party which advocates the use of the death penalty

- Criminal Justice Legal Foundation

- DP Info

- Pro DP Resources

- The Paradoxes of a Death Penalty Stance by Charles Lane in the Washington Post

- Clark County, Indiana, Prosecutor's Page on capital punishment

- In Favor of Capital Punishment - Famous Quotes supporting Capital Punishment

- Studies spur new death penalty debate

Religious views

- The Dalai Lama - Message supporting the moratorium on the death penalty

- Buddhism & Capital Punishment from The Engaged Zen Society

- Orthodox Union website: Rabbi Yosef Edelstein: Parshat Beha'alotcha: A Few Reflections on Capital Punishment

- Jews and the Death Penalty - by Naomi Pfefferman (Jewish Journal)

- Priests for Life - Lists several Catholic links

- The Death Penalty: Why the Church Speaks a Countercultural Message by Kenneth R. Overberg, S.J., from AmericanCatholic.org

- Wrestling with the Death Penalty by Andy Prince, from Youth Update on AmericanCatholic.org

"Capital Punishment". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Catholic_Encyclopedia_(1913)/Capital_Punishment.

"Capital Punishment". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Catholic_Encyclopedia_(1913)/Capital_Punishment.- [6] Roland Nicholson, Pope John Paul II: Mourning and Remebrance, The Catholic Church and the Death Penalty, by Roland Nicholson, Jr.