Hell

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In many religious traditions, Hell is a place of suffering and punishment in the afterlife, often in the underworld. Religions with a linear divine history often depict Hell as endless (for example, see Hell in Christian beliefs). Religions with a cyclic history often depict Hell as an intermediary period between incarnations (for example, see Chinese Diyu).

Punishment in Hell typically corresponds to sins committed in life. Sometimes these distinctions are specific, with damned souls suffering for each wrong committed (see for example Plato's myth of Er or Dante's The Divine Comedy), and sometimes they are general, with sinners being relegated to one or more chamber of Hell or level of suffering. In Islam and Christianity, however, faith and repentance play a larger role than actions in determining a soul's afterlife destiny.

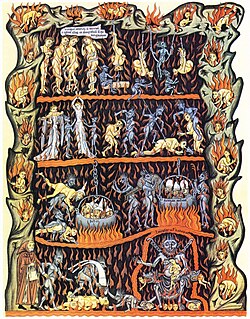

In Christianity and Islam, Hell is traditionally depicted as fiery and painful, inflicting guilt and suffering.[1] Some other traditions, however, portray Hell as cold and gloomy. Despite the common depictions of Hell as a fire, Dante's Inferno portrays the innermost (9th) circle of Hell as a frozen lake of blood and guilt.[2] Hell is often portrayed as populated with demons, who torment the damned. Many are ruled by a death god, such as Nergal, the Hindu Yama, or the Christian Satan.

In contrast to Hell, other types of afterlives are abodes of the dead and paradises. Abodes of the dead are neutral places for all the dead (for example, see sheol) rather than prisons of punishment for sinners. A paradise is a happy afterlife for some or all the dead (for example, see heaven). Modern understandings of Hell often depict it abstractly, as a state of loss rather than as fiery torture literally under the ground.

Contents |

Etymology and Germanic mythology

The modern English word Hell is derived from Old English hel, helle (about 725 AD to refer to a nether world of the dead) reaching into the Anglo-Saxon pagan period, and ultimately from Proto-Germanic *halja, meaning "one who covers up or hides something".[3] The word has cognates in related Germanic languages such as Old Frisian helle, hille, Old Saxon hellja, Middle Dutch helle (modern Dutch hel), Old High German helle (Modern German Hölle), and Gothic halja.[3] Subsequently, the word was used to transfer a pagan concept to Christian theology and its vocabulary[3] (however, for the Judeo-Christian origin of the concept see Gehenna).

The English word hell has been theorized as being derived from Old Norse Hel.[3] Among other sources, the Poetic Edda, compiled from earlier traditional sources in the 13th century, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson, provide information regarding the beliefs of the Norse pagans, including a being named Hel, who is described as ruling over an underworld location of the same name.

Religion, mythology, and folklore

| The neutrality of this section is disputed. Please see the discussion on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until the dispute is resolved. (October 2008) |

Hell appears in several mythologies and religions. It is commonly inhabited by demons and the souls of dead people. Hell is often depicted in art and literature, perhaps most famously in Dante's Divine Comedy.

Polytheism

Ancient Egypt

With the rise of the cult of Osiris during the Middle Kingdom the “democratization of religion” offered to even his most humblest followers the prospect of eternal life, with moral fitness becoming the dominant factor in determining a persons suitability. At death a person faced judgment by a tribunal of forty-two divine judges. If they led a life in conformance with the precepts of of the Goddess Maat, who represented truth and right living, the person was welcomed into the kingdom of Osiris. If found guilty the person was thrown to a “devourer” and didn't share in eternal life.[4] The person who is taken by the devourer is subject first to terrifying punishment and then annihilated. These depictions of punishment may have influenced medieval perceptions of the inferno in hell via early Christian and Coptic texts.[5] Purification for those who are considered justified may be found in the descriptions of “Flame Island”, where they experience the triumph over evil and rebirth. For the dammed complete destruction into a state of non being awaits but there is no suggestion of eternal torture.[6][7] Divine pardon at judgement was always a central concern for the Ancient Egyptians.[8]

Greek

In classic Greek mythology, below Heaven, Earth, and Pontus is Tartarus, or Tartaros (Greek Τάρταρος, deep place). It is either a deep, gloomy place, a pit or abyss used as a dungeon of torment and suffering that resides within Hades (the entire underworld) with Tartarus being the hellish component. In the Gorgias, Plato (c. 400 BC) wrote that souls were judged after death and those who received punishment were sent to Tartarus. As a place of punishment, it can be considered a hell. The classic Hades, on the other hand, is more similar to Old Testament Sheol.

European

The hells of Europe include Breton Mythology's “Anaon”, Celtic Mythology's “Uffern”, Slavic mythology's "Peklo", the hell of Lapps Mythology and Ugarian Mythology's “Manala” that leads to annihilation. The hells in the Middle East include Sumerian Mythology's “Aralu”; the hells of Canaanite Mythology, Hittite Mythology and Mithraism; the weighing of the heart in Egyptian Mythology can lead to annihilation. The hells of Asia include Bagobo Mythology's “Gimokodan” and Ancient Indian Mythology's “Kalichi". African hells include Haida Mythology's “Hetgwauge” and the hell of Swahili Mythology. The hells of the Americas include Aztec Mythology's “Mictlan”, Inuit mythology's “Adlivun” and Yanomamo Mythology's “Shobari Waka”. The Oceanic hells include Samoan Mythology's “O le nu'u-o-nonoa” and the hells of Bangka Mythology and Caroline Islands Mythology.

Americas

In Maya mythology , Xibalbá is the dangerous underworld of nine levels ruled by the demons Vucub Caquix and Hun Came. The road into and out of it is said to be steep, thorny and very forbidding. Metnal is the lowest and most horrible of the nine Hells of the underworld, ruled by Ah Puch. Ritual healers would intone healing prayers banishing diseases to Metnal. Much of the Popol Vuh describes the adventures of the Maya Hero Twins in their cunning struggle with the evil lords of Xibalbá.

The Aztecs believed that the dead traveled to Mictlán, a neutral place found far to the north. There was also a legend of a place of white flowers, which was always dark, and was home to the gods of death, particularly Mictlantecutli and his spouse Mictlantecihuatl, which means literally "lords of Mictlán". The journey to Mictlán took four years, and the travelers had to overcome difficult tests, such as passing a mountain range where the mountains crashed into each other, a field where the wind carried flesh-scraping knives, and a river of blood with fearsome jaguars.

Abrahamic

Judaism

Daniel 12:2 proclaims "And many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, Some to everlasting life, Some to shame and everlasting contempt." Judaism does not have a specific doctrine about the afterlife, but it does have a mystical/Orthodox tradition of describing Gehenna. Gehenna is not Hell, but rather a sort of Purgatory where one is judged based on his or her life's deeds, or rather, where one becomes fully aware of one's own shortcomings and negative actions during one's life. The Kabbalah describes it as a "waiting room" (commonly translated as an "entry way") for all souls (not just the wicked). The overwhelming majority of rabbinic thought maintains that people are not in Gehenna forever; the longest that one can be there is said to be 11 months, however there has been the occasional noted exception. Some consider it a spiritual forge where the soul is purified for its eventual ascent to Olam Habah (heb. עולם הבא; lit. "The world to come", often viewed as analogous to Heaven). This is also mentioned in the Kabbalah, where the soul is described as breaking, like the flame of a candle lighting another: the part of the soul that ascends being pure and the "unfinished" piece being reborn.

According to Jewish teachings, hell is not entirely physical; rather, it can be compared to a very intense feeling of shame. People are ashamed of their misdeeds and this constitutes suffering which makes up for the bad deeds. When one has so deviated from the will of God, one is said to be in gehinom. This is not meant to refer to some point in the future, but to the very present moment. The gates of teshuva (return) are said to be always open, and so one can align his will with that of God at any moment. Being out of alignment with God's will is itself a punishment according to the Torah. In addition, Subbotniks and Messianic Judaism believe in Gehenna, but Samaritans probably believe in a separation of the wicked in a shadowy existence, Sheol, and the righteous in heaven.

Christianity

The Christian doctrine of hell derives from the teaching of the New Testament, where hell is typically described using the Greek words Tartarus or Hades or the Hebrew word Gehenna. Hell is taught as the final destiny of those who have not accepted Jesus Christ as their savior after they have passed through the great white throne of judgment [9] [10], where they will be punished for sin and permanently separated from God after the general resurrection and last judgment. However, many Christian theologians of the early Church and some of the modern Church subscribe to the doctrines of conditional immortality ("annihilationism") or universal reconciliation. [11][12][13] According to most Christian teachings, Hell described as being a great lake of fire, where the damned are burned and tortured eternally.

Islam

Muslims believe in jahannam (in Arabic: جهنم) (which is related to the Hebrew word gehinnom and resembles the versions of Hell in Christianity). In the Qur'an, the holy book of Islam, there are literal descriptions of the condemned in a fiery Hell, as contrasted to the garden-like Paradise (jannah) enjoyed by righteous believers.

In addition, Heaven and Hell are split into many different levels depending on the actions perpetrated in life, where punishment is given depending on the level of evil done in life, and good is separated into other levels depending on how well one followed God while alive. The gate of Hell is guarded by Maalik who is the leader of the angels assigned as the guards of hell also known as Zabaaniyah. The Quran states that the fuel of Hellfire is rocks/stones (idols) and human beings.

Although generally Hell is often portrayed as a hot steaming and tormenting place for sinners, there is one Hell pit which is characterized differently from the other Hell in Islamic tradition. Zamhareer is seen as the coldest and the most freezing Hell of all; yet its coldness is not seen as a pleasure or a relief to the sinners who committed crimes against God. The state of the Hell of Zamhareer is a suffering of extreme coldness, of blizzards, ice, and snow which no one on this earth can bear. The lowest pit of all existing Hells is the Hawiyah which is meant for the hypocrites and two-faced people who claimed to believe in Allah and His messenger by the tongue but denounced both in their hearts. Hypocrisy is considered to be the most dangerous sin of all (despite the fact that Shirk is the greatest sin viewed by Allah). According to the Qur'an, all non-believers who have received and rejected Islamic teachings will go to Hell.

Bahai Faith

The Bahá'í Faith regards the conventional description of Hell (and heaven) as a specific place as symbolic.[14] Instead the Bahá'í writings describe Hell as a "spiritual condition" where remoteness from God is defined as Hell; conversely heaven is seen as a state of closeness to God.[14]

Eastern

Buddhism

Buddhism teaches that there are five (sometimes six) realms of rebirth, which can then be further subdivided into degrees of agony or pleasure. Of these realms, the hell realms, or Naraka, is the lowest realm of rebirth. Of the hell realms, the worst is Avīci or "endless suffering". The Buddha's disciple, Devadatta, who tried to kill the Buddha on three occasions, as well as create a schism in the monastic order, is said to have been reborn in the Avici Hell.

However, like all realms of rebirth, rebirth in the Hell realms is not permanent, though suffering can persist for eons before being reborn again. In the Lotus Sutra, the Buddha teaches that eventually even Devadatta will become a Buddha himself, emphasizing the temporary nature of the Hell realms. Thus, Buddhism teaches to escape the endless migration of rebirths (both positive and negative) through the attainment of Nirvana.

The Bodhisattva Ksitigarbha, according to the Ksitigarbha Sutra, made a great vow as a young girl to not reach Enlightenment until all beings were liberated from the Hell Realms or other unwholesome rebirths. In popular literature, Ksitigarbha travels to the Hell realms to teach and relieve beings of their suffering.

Hinduism

17th century Painting from Government Museum, Chennai.

In Hinduism, there are different opinions from various schools of thought on Hell which is called Naraka (in Sanskrit: नर्क). For some it is metaphorical, or a lower spiritual plane (called Naraka Loka) where the spirit is judged, or partial fruits of karma affected in a next life. In Mahabharata there is a mention of the Pandavas going to Heaven and the Kauravas going to Hell. However for the small number of sins which they did commit in their lives, the Pandavas had to undergo hell for a short time. Hells are also described in various Puranas and other scriptures. Garuda Purana gives a detailed account of Hell, its features and enlists amount of punishment for most of the crimes like a modern day penal code.

It is believed that people who commit sins go to Hell and have to go through punishments in accordance with the sins they committed. The god Yamaraj, who is also the god of death, presides over Hell. Detailed accounts of all the sins committed by an individual are kept by Chitragupta, who is the record keeper in Yama's court. Chitragupta reads out the sins committed and Yama orders appropriate punishments to be given to individuals. These punishments include dipping in boiling oil, burning in fire, torture using various weapons, etc. in various Hells. Individuals who finish their quota of the punishments are reborn in accordance with their balance of karma. All created beings are imperfect and thus have at least one sin to their record; but if one has generally led a pious life, one ascends to Paradise, or Swarga after a brief period of expiation in Hell.

Taoism

Ancient Taoism had no concept of Hell, as morality was seen to be a man-made distinction and there was no concept of an immaterial soul. In its home country China, where Taoism adopted tenets of other religions, popular belief endows Taoist Hell with many deities and spirits who punish sin in a variety of horrible ways. This is also considered Karma for Taoism.

Chinese folk beliefs

Diyu (traditional Chinese: 地獄; simplified Chinese: 地狱; pinyin: Dìyù; Wade-Giles: Ti-yü; literally "earth prison") is the realm of the dead in Chinese mythology. It is very loosely based upon the Buddhist concept of Naraka combined with traditional Chinese afterlife beliefs and a variety of popular expansions and re-interpretations of these two traditions. Ruled by Yanluo Wang, the King of Hell, Diyu is a maze of underground levels and chambers where souls are taken to atone for their earthly sins.

Incorporating ideas from Taoism and Buddhism as well as traditional Chinese folk religion, Diyu is a kind of purgatory place which serves not only to punish but also to renew spirits ready for their next incarnation. There are many deities associated with the place, whose names and purposes are the subject of much conflicting information.

The exact number of levels in Chinese Hell - and their associated deities - differs according to the Buddhist or Taoist perception. Some speak of three to four 'Courts', other as many as ten. The ten judges are also known as the 10 Kings of Yama. Each Court deals with a different aspect of atonement. For example, murder is punished in one Court, adultery in another. According to some Chinese legends, there are eighteen levels in Hell. Punishment also varies according to belief, but most legends speak of highly imaginative chambers where wrong-doers are sawn in half, beheaded, thrown into pits of filth or forced to climb trees adorned with sharp blades.

However, most legends agree that once a soul (usually referred to as a 'ghost') has atoned for their deeds and repented, he or she is given the Drink of Forgetfulness by Meng Po and sent back into the world to be reborn, possibly as an animal or a poor or sick person, for further punishment.

Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism has historically suggested several possible fates for the wicked, including annihilation, purgation in molten metal, and eternal punishment, all of which have standing in Zoroaster's writings. Zoroastrian eschatology includes the belief that wicked souls will remain in hell until, following the arrival of three saviors at thousand-year intervals, Ahura Mazda reconciles the world, destroying evil and resurrecting tormented souls to perfection.[15]

The sacred Gathas mention a “House of the Lie″ for those “that are of an evil dominion, of evil deeds, evil words, evil Self, and evil thought, Liars.”[16] However, the only Zoroastrian text that describes hell in detail is the Book of Arda Viraf.[17] It depicts particular punishments for particular sins -- for instance, being trampled by cattle as punishment for neglecting the needs of work animals.[18]

Literature

In his Divina commedia ("Divine comedy"; set in the year 1300), Dante Alighieri employed the conceit of taking Virgil as his guide through Inferno (and then, in the second cantiche, up the mountain of Purgatorio). Virgil himself is not condemned to Hell in Dante's poem but is rather, as a virtuous pagan, confined to Limbo just at the edge of Hell. The geography of Hell is very elaborately laid out in this work, with nine concentric rings leading deeper into the Earth and deeper into the various punishments of Hell, until, at the center of the world, Dante finds Satan himself trapped in the frozen lake of Cocytus. A small tunnel leads past Satan and out to the other side of the world, at the base of the Mount of Purgatory.

John Milton's Paradise Lost (1667) opens with the fallen angels, including their leader Satan, waking up in Hell after having been defeated in the war in heaven and the action returns there at several points throughout the poem. Milton portrays Hell as the abode of the demons, and the passive prison from which they plot their revenge upon Heaven through the corruption of the human race. 19th century French poet Arthur Rimbaud alluded to the concept as well in the title and themes of one of his major works, A Season In Hell. Rimbaud's poetry portrays his own suffering in a poetic form as well as other themes.

Many of the great epics of European literature include episodes that occur in Hell. In the Roman poet Virgil's Latin epic, the Aeneid, Aeneas descends into Dis (the underworld) to visit his father's spirit. The underworld is only vaguely described, with one unexplored path leading to the punishments of Tartarus, while the other leads through Erebus and the Elysian Fields.

The idea of Hell was highly influential to writers such as Jean-Paul Sartre who authored the 1944 play "No Exit" about the idea that "Hell is other people". Although not a religious man, Sartre was fascinated by his interpretation of a Hellish state of suffering. C.S. Lewis's The Great Divorce (1945) borrows its title from William Blake's Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1793) and its inspiration from the Divine Comedy as the narrator is likewise guided through Hell and Heaven. Hell is portrayed here as an endless, desolate twilight city upon which night is imperceptibly sinking. The night is actually the Apocalypse, and it heralds the arrival of the demons after their judgment. Before the night comes, anyone can escape Hell if they leave behind their former selves and accept Heaven's offer, and a journey to Heaven reveals that Hell is infinitely small; it is nothing more or less than what happens to a soul that turns away from God and into itself.

Piers Anthony in his series Incarnations of Immortality portrays examples of Heaven and Hell via Death, Fate, Nature, War, Time, Good-God, and Evil-Devil. Robert A. Heinlein offers a yin-yang version of Hell where there is still some good within; most evident in his book Job: A Comedy of Justice. Lois McMaster Bujold uses her five Gods 'Father, Mother, Son, Daughter and Bastard' in The Curse of Chalion with an example of Hell as formless chaos. Michael Moorcock is one of many who offer Chaos-Evil-(Hell) and Uniformity-Good-(Heaven) as equally unacceptable extremes which must be held in balance; in particular in the Elric and Eternal Champion series.

Biblical words translated as "Hell"

- Sheol

- In the King James Bible, the Old Testament term Sheol is translated as "Hell" 31 times.[19] However, Sheol was translated as "the grave" 31 other times.[20] Sheol is also translated as "the pit" three times.[21]

- Modern translations, however, do not translate Sheol as "Hell" at all, instead rendering it "the grave," "the pit," or "death." See Intermediate state.

- Gehenna

- In the New Testament, both early (i.e. the KJV) and modern translations often translate Gehenna as "Hell."[22] Young's Literal Translation is one notable exception, simply using "Gehenna", which was in fact a geographic location just outside Jerusalem (the Valley of Hinnom).

- Tartarus

- Appearing only in II Peter 2:4 in the New Testament, both early and modern translations often translate Tartarus as "Hell." Again, Young's Literal Translation is an exception, using "Tartarus".

- Hades

- Hades is the Greek word traditionally used for the Hebrew word Sheol in such works as the Septuagint, the Greek translations of the Hebrew Bible. Like other first-century Jews literate in Greek, Christian writers of the New Testament followed this use. While earlier translations (i.e. the KJV) most often translated Hades as "hell", modern translations use the transliteration "Hades" or render the word as "the grave" in most contexts. See Intermediate state.

- Infernus

- The Latin word infernus means "being underneath" and is often translated as "Hell".

References

- ^ Numerous verses in the Qu'ran and New Testament.

- ^ Alighieri, Dante (June 2001 (orig. trans. 1977)) [c. 1315]. "Cantos XXXI-XXXIV". Inferno. trans. John Ciardi (2 ed.). New York: Penguin.

- ^ a b c d Barnhart, Robert K. (1995) The Barnhart Concise Dictionary of Etymology, page 348. Harper Collins ISBN 0062700847

- ^ Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt”, Rosalie David, p158-159, Penguin, 2002, ISBN 0-14-0262252-0

- ^ ”The Essential Guide to Egyptian Mythology: The Oxford Guide”, “Hell”, p161-162, Jacobus Van Dijk, Berkley Reference, 2003, ISBN 0-425-19096-X

- ^ ”The Divine Verdict”, John Gwyn Griffiths, p233, BRILL, 1991, ISBN 9004092315

- ^ see also letter by Prof. Griffith to “The Independent”, 32 December 1993[1]

- ^ "Egyptian Religion", Jan Assman, The Encyclopedia of Christianity, p77, vol2, Wm. B Eerdmans Publishing, 1999, ISBN 90041 16958

- ^ Revelation 20:11

- ^ Romans 6:23

- ^ New Bible Dictionary, "Hell", InterVarsity Press, 1996.

- ^ New Dictionary of Biblical Theology, "Hell", InterVarsity Press, 2000.

- ^ Evangelical Alliance Commission on Truth and Unity Among Evangelicals, The Nature of Hell, Paternoster, 2000.

- ^ a b Masumian, Farnaz (1995). Life After Death: A study of the afterlife in world religions. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. ISBN 1-85168-074-8.

- ^ Meredith Sprunger. "An Introduction to Zoroastrianism". http://www.ubfellowship.org/archive/readers/601_zoroastrianism.htm. Retrieved on 2008-10-10.

- ^ Yasna 49:11, "Avesta: Yasna". http://www.avesta.org/yasna/y47to50b.htm. Retrieved on 2008-10-11.

- ^ Eileen Gardiner (2006-02-10). "About Zoroastrian Hell". http://www.hell-on-line.org/AboutZOR.html#The%20Fate%20of%20the%20Soul. Retrieved on 2008-10-10.

- ^ Chapter 75, "The Book of Arda Viraf". http://www.avesta.org/pahlavi/viraf.html. Retrieved on 2008-10-10.

- ^ Deut. 32:22, Deut. 32:36a & 39, II Sam. 22:6, Job 11:8, Job 26:6, Psalm 9:17, Psalm 16:10, Psalm 18:5, Psalm 55:15, Psalm 86:13, Ps. 116:3, Psalm 139:8, Prov. 5:5, Prov. 7:27, Prov. 9:18, Prov. 15:11, Prov. 15:24, Prov. 23:14, Prov. 27:20, Isa. 5:14, Isa. 14:9, Isa. 14:15, Isa. 28:15, Isa. 28:18, Isa. 57:9, Ezek. 31:16, Ezek. 31:17, Ezek. 32:21, Ezk. 32:27, Amos 9:2, Jonah 2:2, Hab. 2:5

- ^ Gen. 37:35, Gen. 42:38, Gen. 44:29, Gen. 44:31, I Sam. 2:6, I Kings 2:6, I Kings 2:9, Job 7:9, Job 14:13, Job 17:13, Job 21:13, Job 24:19, Psalm 6:5, Psalm 30:3, Psalm 31:17, Psalm 49:14, Psalm 49:14, Psalm 49:15, Psalm 88:3, Psalm 89:48, Prov. 1:12, Prov. 30:16, Ecc. 9:10, Song 8:6, Isa. 14:11, Isa. 38:10, Isa. 38:18, Ezek. 31:15, Hosea 13:14, Hosea 13:14, Psalm 141:7

- ^ Num. 16:30, Num. 16:33, Job 17:16

- ^ Mat. 5:29, Mat. 5:30, Matt. 10:28, Matt. 23:15, Matt. 23:33, Mark 9:43, Mark 9:45, Mark 9:47, Luke 12:5, Matt. 5:22, Matt. 18:9, Jas. 3:6

- ^ Roget's Thesaurus, VI.V.2, "Hell"

See also

Further reading

- Jonathan Edwards, The Justice of God in the Damnation of Sinners. Diggory Press, ISBN 978-1846856723

- Thomas Boston, Hell. Diggory Press, ISBN 978-1846857485

- John Bunyan, A Few Sighs from Hell (Or The Groans of the Damned Soul). Diggory Press, ISBN 978-1846857270

- Metzger, Bruce M. (ed); , Michael D. Coogan (ed) (1993). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504645-5.

External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Hell |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Hell |

- Atheist Foundation of Australia – 666 words about hell.

- The Jehovah's Witnesses perspective

- Dying, Yamaraja and Yamadutas + terminal restlessness

- example Buddhist Hells

|

|||||||||